Documentation of Constructive Innovation Assessment (CINA) workshops:

InnoForESt Innovation Region Čmelak, Czech Republic (and Hybe, Slovakia)

D4.2 subreport

Main authors: Martin Špaček, Tatiana Kluvánková, Jiří Louda, Lenka Dubová

Edited by: Ewert Aukes, Peter Stegmaier

List of Figures

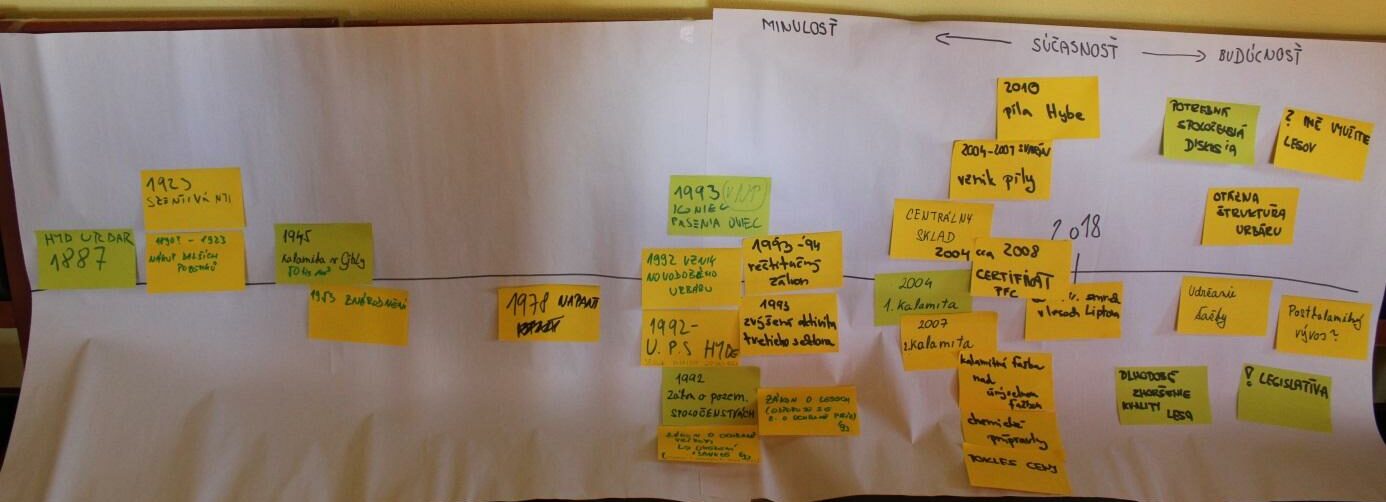

- Figure 1: Timeline of innovation in the Land trust Hybe (Source: InnoForESt workshop in Hybe (Urbar Hybe, 2018)).

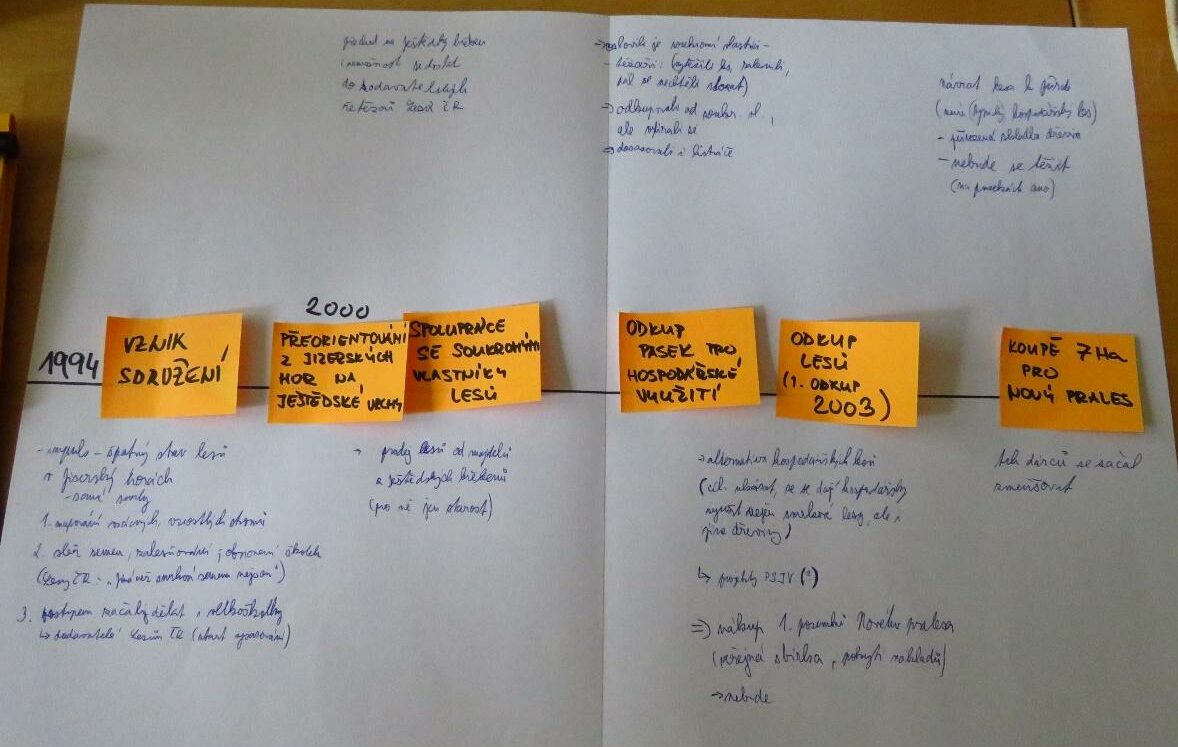

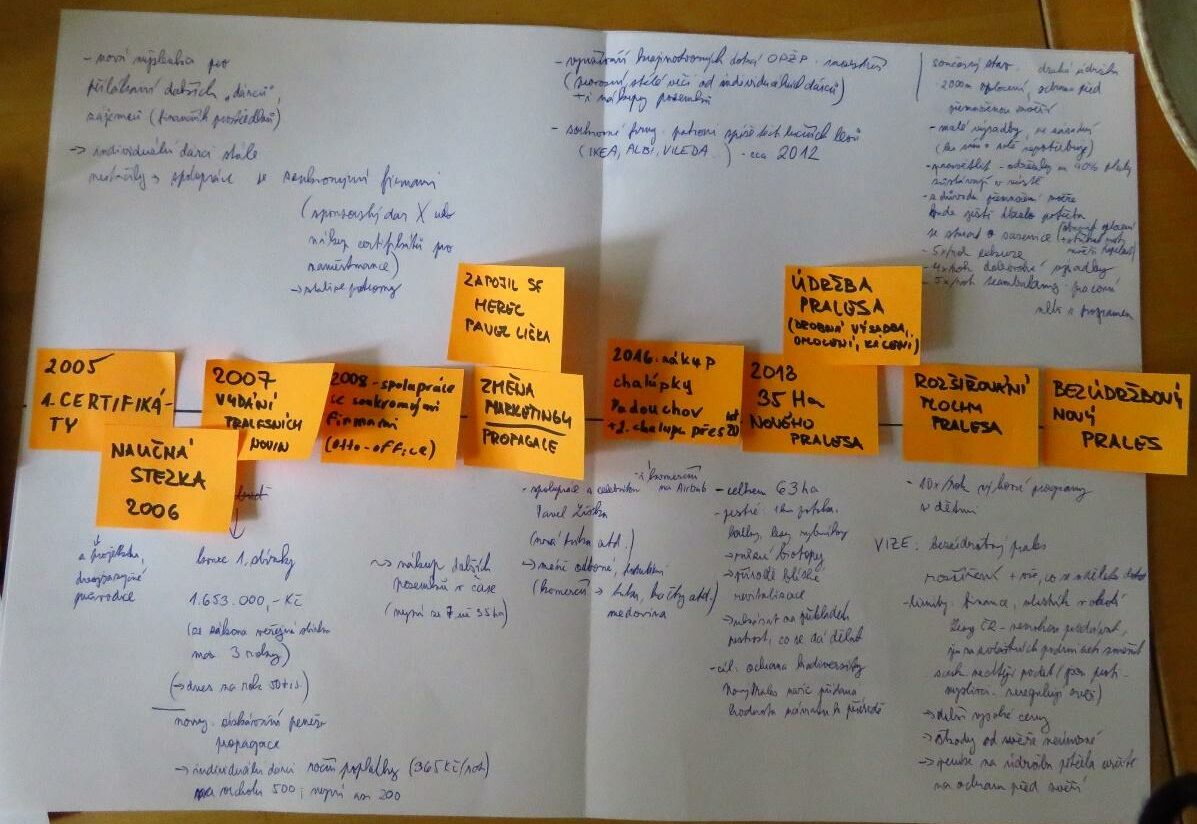

- Figure 2: Timeline of innovation in the Land trust Cmelak (Part 1) (Source: InnoForESt focus group in Liberec (Liberec, 2018)).

- Figure 3: Timeline of innovation in the Land trust Cmelak (Part 2).

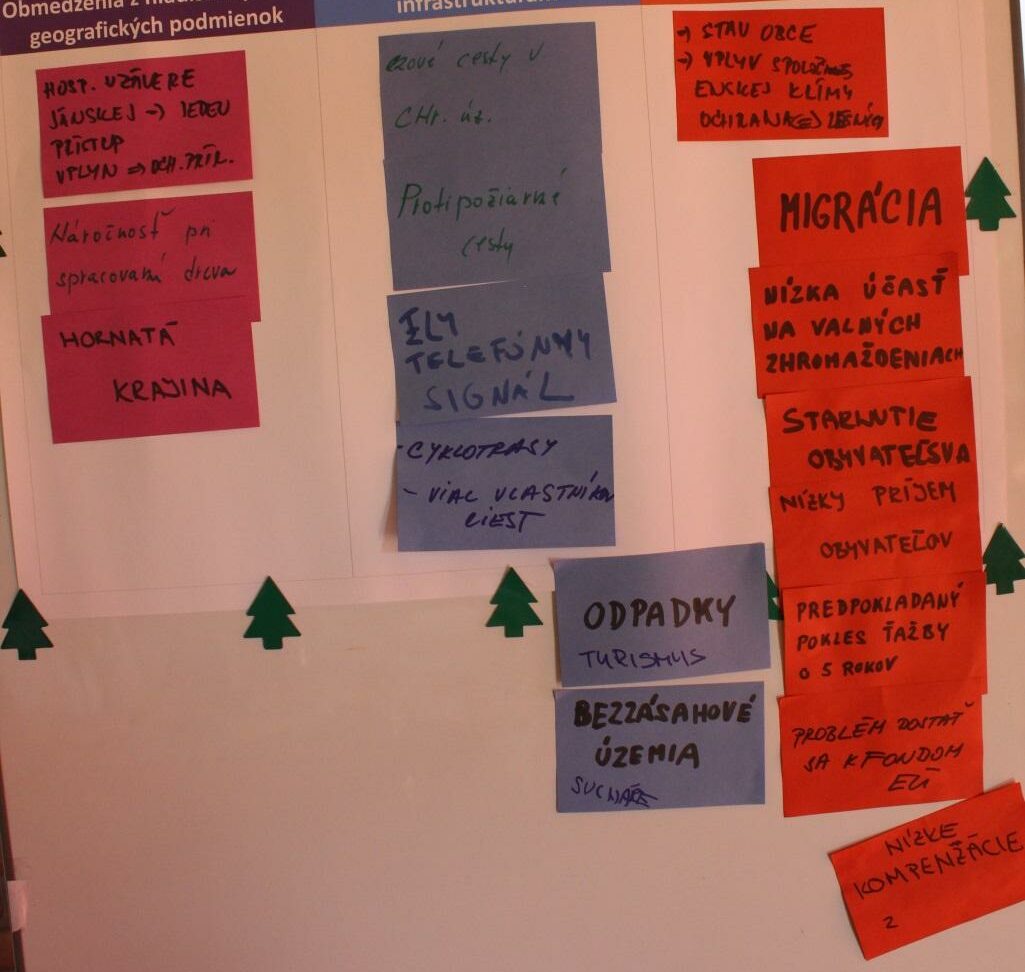

- Figure 4: Key issues for Land trust Hybe (Slovakia) (Source: InnoForESt workshop in Hybe (Urbar Hybe, 2018)).

- Figure 5: Identification of key “motivation” factors (Source: InnoForESt workshop in Hybe (Urbar Hybe, 2018)).

- Figure 6: Key “motivation” factors identified (Source: InnoForESt workshop in Hybe (Urbar Hybe, 2018)).

- Figure 7: Selection of key “motivation” factors identified (Liberec, Czechia).

- Figure 8: Assessment of key “motivation” factors identified (Liberec, Czechia).

List of Tables

- Table 1: History of Forest commons Hybe according to workshop participants (Urbar Hybe, 2018).

- Table 2: History of land trust Čmelak identified during focus group meeting (Čmelak, 2018).

- Table 3: Actors in the Čmelak and Hybe Innovation Regions.

- Table 4: First scenario versions.

- Table 5: Results from factors assessment (Liberec, Czechia).

- Table 6: Comparison of factors reconfiguration for Czech and Slovak innovation region.

Abbreviations

| CINA | Constructive Innovation Assessment |

| CZ | Czech Republic |

| FES | Forest Ecosystem Services |

| IR | Innovation Region |

| PES | Payments for ecosystem services |

| RBG | Role Board Game |

| SK | Slovak Republic |

1 Introduction

1.1 Overall case description

The Innovation Region “Hybrid ecosystem service governance Slovakia/Czech Republic” is based on collective action of self-organized long lasting institution, such as forest commons in a sense of common forests owned/managed by group of individuals i) with shared ownership of forest, or ii) who are members of land trust. The collective actions address the social dilemma of balancing individual interests to forest overuse over societal interest in sustainable forest ecosystem services provision. Of particular importance are climate regulation, biodiversity, recreation and education are concerned. The locations are in the Forest commons Hybe (SK) and Land Trust Association Čmelak (CZ) where in both innovative “collective actions” were developed based on self-organization of the community.

Self-organized institutions provide forest ecosystem services based on adaptability and flexibility of members in forest commons (private property – jointly owned) and land trusts (non-governmental organization). This enables innovative practices in forest management to support the provision of non-timber forest products and services, in particular enables the evolution of nature-based forestry. Whereas in Slovakia forest commons have a long history and tradition of the self-organised forest communities goes back to 18th century, in Czechia the innovative activities based on self-organization in the Land association Čmelak started in the 1990s. Both communities are characterized by a relatively rapid response to the various challenges they face in their activities, and thus the willingness to introduce innovative approaches in forestry.

Although governance of both examples covered by the innovation region is based on self-organization, some differences can be identified. There is the difference in the focus of their activities, development of innovative activities, size, number of involved stakeholders, way of management, sources of financing, etc. Whereas Čmelak is more oriented towards the nature protection and conservation and is already advanced in innovative activities (such as provision of non-timber forest product and services, growing own seedlings, using PES schemes like certificates) in forestry, the Forest commons Hybe is more business oriented and introduction of innovative activities (e.g. carbon forestry) is still being considered. Financing of the forest management under the Čmelak is not self-sufficient and is in demand for external funding. In the Forest commons Hybe revenues come from forestry activities. Čmelak implement its activities on relatively small area whereas the Forest commons Hybe is to steer several times larger territory. Due to the specific position of Čmelak many different stakeholders are involved and have influence on innovation activities.

1.2 Problem background

This part of the analysis is mainly based on outputs from Workshop with stakeholders of Urbar Hybe (Urbar Hybe, 2018), and Roundtable (focus group) with stakeholders of Čmelak (Čmelak, 2018).

In response to natural disturbances (forest wind calamities and following bark beetle calamities), the Forest commons Hybe adopted a new management strategy and plan, introducing natural regeneration and intensive communication between members in order to improve their economic balance. The new forest management plan supports a natural regeneration of forests such as use of local seeds (instead of buying tree seedlings from certified companies but less resilient due to growing them in different climatic conditions). It led to increased forests resilience, reductions of pests and costs savings. More intensive communication between the members as well as with state institutions was introduced to change attitudes of members, mitigate conflicts among them and to enforce adaptation of forest management closer to carbon smart forestry. The reforestation of damaged forests results in young diverse forests that are not only spruce monocultures and increase the carbon sequestration. All the activities are aiming to increase forest resilience and well-being of the local community and other users of forest ecosystem services (opportunities for recreation) and contribution to climate change mitigation by carbon sequestration (Urbar Hybe, 2018).

In Čmelak, studied innovative activities towards more diversified New virgin forest are based on the sale of “certificates of patronage”, cooperation with companies, public grants as well as voluntary work of association members. However, the financial sources from selling certificates (used for buying new land) is decreasing, as well as money from public grants (used for forest management activities). In the beginning public expressed positive interest (public money collection, certificates, volunteers), but innovation doesn’t currently attract new buyers. Buyers bought the certificates mostly only one time, they do not buy it again/repeatedly, thus it is only one-off source of money. In these days it seems, that most of the potential buyers have bought the certificates, number of new buyers is decreasing. Therefore, Čmelak is looking for some new product/innovation which will bring continuous sources of money (Čmelak, 2018).

In both communities there is income stagnation these days and they are searching for new opportunities to finance their innovative activities. So far, innovative activities are not really based on any policy instruments and they are based on the (voluntary) activities of the community members and management. It shows, that sustainable forestry in common forests is possible, but it is time demanding and it needs much of enthusiasm and effort by members of the communities.

Activities are partly perceived as negative by some groups of stakeholders. For, example the president of the land trust Čmelak is an important local politician and due to the connection with his public function some activities are seen in negative light (this is supported mainly by opposition). In Urbar Hybe some activities after natural disturbances are seen as negative by environmental NGOs because of the calamity harvesting in National Park as well as because of slow reforestation after calamity (due to natural reforestation which is more time consuming). Calamity harvesting is realized after natural disturbances such as forest wind calamities or bark beetle calamities. It is not planned harvesting following the forest plans.

2 Case overview

2.1 Case history

Although the studied communities in the two countries have evolved for different time periods (in Slovakia from 1880s, in Czechia from 1990s), they are both based on long-lasting institutions, which enable promotion of innovative activities. Over time, members of communities increase their knowledge and build trust among each other. They have courage and willingness to work together and improve the management of their forest. Innovations were in general accepted well. There were problems with game hunters and in consequence with public administration of game hunting (in Czechia), forest protection and environmental NGOs (Slovakia). Slovakian environmental activists and NGOs tried to delay calamity harvesting in National Park arguing for natural self-restoration of the forest. The Hybe community perceived this very negatively, because they tried to harvest bark-beetle-infected trees as quickly as possible to prevent further spread to healthy trees and subsequent additional economic damage to the community.

| 1887 | Establishment of the Forest commons Hybe |

| 1890-1923 | They bought more land and forests |

| 1953 | Nationalization of the community property by communists |

| 1978 | Establishment of the National Park Low Tatra Mountains (it covers part of the forests of Forest commons Hybe) |

| 1992 | Denationalisation after fall of socialism and the emergence of the modern Forest commons Hybe |

| 1993 | Changes in national law and more restrictions in forest management |

| 2004 | Wind calamity which destroyed significant part of the forests after which new forest management plan was developed and new young forest with higher biodiversity was established |

| 2007 | Wind calamity which destroyed significant part of the forests – it also contributed to reduction of wood prices in following years |

| 2008 | Get the PEFC certificate from Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) |

| 2010 | Establishment of own sawmill to process own wood – till now the potential capacity is not fully used |

| 2017 | Discussion about future income opportunities started |

| 1994 | Establishment of the association/land trust Čmelak, start of activities towards restoring mixed forest damaged by bark beetles in Jizerske mountains, cultivation of diverse seedling (instead of planted spruce monoculture) |

| 2000 | Movement of all activities of Čmelak from Jizerske Mountains to Podještědí (under Jested mountain near Liberec city), sale of diverse seedlings to private owners |

| 2003 | Establishment of New Virgin Forest, purchase of the first land (7 ha), public money collection (other land bought more or less continuously during the following years) |

| 2005 | Sale of the first Certificate – new source of money (income from public collection has stagnated later), sales to private persons, citizens; resources for forest managing, reforestation, buy up land /glades |

| 2006 | Use of subsidies from grant schemes, creation of nature trail forest management in the New Virgin Forest |

| 2008 | The first cooperation with companies – sponsorship, mainly for the maintenance of glades, new marketing, new form of promotion (spots etc.) |

| 2016 | purchase of cottage close to the site of New Virgin Forest – the possibility to stay for those interested in New Virgin Forest (recreation) and educational programs for schools |

| 2019 | Current state: 35 ha of New virgin forest, 63 ha total (glades, wetlands, forests) |

2.2 Brief stakeholder constellation

The innovations in this innovation region are based on the community members themselves. Their self-organisation and ability to resist social (e.g. new legislation) and natural disturbances (e.g. forest wind calamities) and to act on them are considered as the key factors for innovation. The study concerns two communities in the two countries with long-lasting institutions as the governance innovation. These institutions address the social dilemma of balancing individual interests to overuse forests and the societal interest in sustainable forest ecosystem services provision regardless of property rights (Schlager and Ostrom, 1992; see also chapter 1.1). In particular, climate regulation, biodiversity, recreation and education are concerned. The key question addressed is how collective/community rules-in-use in different governance structures may stimulate innovation to sustainable FES provision in the long term. We perform the study on two historically, politically, geographically and institutionally similar examples with different property relations.

Legislation in both countries struggles with conflicts between forest protection and forestry standards, e.g. while Forest laws command the removal of fallen wood from the forest, Nature Protection laws prohibit this and do not permit remove fallen wood from the forests without long permission process which results in spreading of the bark beetle (Brnkaľáková, 2016).

The forest commons Hybe and its forests are located in the municipality Hybe, Northern Slovakia and surroundings. The ecological forest borders are clearly identified. However, social boundaries align with the traditional commons regime established by historical Austro-Hungarian Law, which was adopted in modern Slovak legislation (called “urbar”). In urbars, community members share property by ideal share and rules-in-use follow common pool resource regime principles (Ostrom, 2009). Urbars are nested in national legal forest management and governance structures. External actors may not always understand and support their innovative activities leading to various disputes.

Čmelak is a relatively newly established land trust in the form of NGO, whose members decide jointly about forest activities (as members, the board or during the membership meeting). The broader network of actors consists of forest experts, volunteers, game hunters and private donors and sponsors, who bought patronage certificates of the New Virgin Forest. This constitutes a new, certificate-based common pool resource regime as a means for a virtually-shared forest ownership established by rules-in-use (especially in relation to the ways of the forest management), instead of legally-shared property ownership. This novel governance structure is not embedded in the Czech national legislation system. Čmelak is the innovator and its members – some of whom work on-site as volunteers – support the innovation. Most stakeholders perceive the innovation and Čmelak’s activities as positive, except for game hunters and public administration of hunting (because of fences in the forest to protect the fledgling virgin forest from damage caused by wild animals, see stakeholder analysis).

Forest experts play a very important role. In general, these experts are assigned by the public administration to help the smaller forest owners with forest management and to secure compliance with the Forest law. The specific forest expert who is collaborating with Čmelák is very open to innovation and supports the activities of Čmelak (but this is not the case for all forest experts). Beneficiaries from the innovative activities are not only members of local forest communities but also wider society because there are multiple ecosystem services are provided by forests (mostly regulation and cultural services).

(* SME (Small and medium enterprises) // ** PR (Private), PU (Public), PU-PR (Public-Private), C (Collective) // *** L (Local), R (Regional), N (National), I (International) // **** L (Low), A (Average), H (High))

| Stakeholder (CETIP, IREAS) | Stakeholder category (UIBK) * | Sphere ** | Business type | Scale *** | Openness to innovation **** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Čmelák z.s. | Civil society actors / land- and forest owners | PR/C | Forest and natural resource management (forest/nature conservation)/ forestry service | L | H |

| Forest expert | Public administration | PU-PR | Forest management and consulting service | L | H |

| Department of Planning Authority | Public administration | PU | Forest and natural resource management | R | L |

| Department of Forest Protection | Public administration | PU | Forest and natural resource management / Forestry service | R | L |

| Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic | Protected areas organization | PU | Forest and natural resource management | N | M |

| National ministries | Public administration | PU | Forest and natural resource management / Forestry service | N | L |

| Self-governed region | Public administration | PU | Regional development and nature conservation | R | L |

| Small municipalities | Land- and forest owners | PU | Forest and natural resource management / Tourism/ forestry service | L | L |

| Municipality of Liberec | Public administration | PU | Regional development and nature conservation | L | L |

| State Environmental Fund | Public administration | PU | Funding sponsor and consulting service | N | M |

| State Administration of Hunting | Public administration | PU | Natural resource management | L-R | L |

| Volunteers | Recreational users | PR | Nature conservation | L-R | M |

| Tourists | Recreational users | PR | Tourism | L | L |

| Neighboring forest owners | Land- and forest owners | PU-PR | Forest and natural resource management/ forestry service | L-R | L |

| Land trusts | Land- and forest owners/ Civil society actors | C | Forest and natural resource management/ forestry service | L | L |

| Supporters | Financial enterprises | PR | Funding sponsor | L-R | H |

| Environmental NGOs | Civil society actors | C | Nature conservation | N/R/L | L |

| Businesses | SME | PR | Funding sponsor | R | M |

| Scientists, experts | Scientific organizations | PU-PR | Research and consulting | R-N | M-H |

| Local citizens | Recreational users | PR | Recreation/tourism | L | L |

| Environmental inspection | Public administration | PU | Nature conservation | N | L |

| Game hunters | Civil society actors | C | Game hunting | L | L |

| Forest commons Hybe | Cooperation network and consulting cluster | C | Forest and natural resource management / Forestry service | L | H |

| National Park Low Tatra Mountains | Protected areas organizations | PU | Forest and natural resource management/ Nature conservation | R-N | M |

| Slovak government | Public administration | PU | Forest and natural resource management/ Nature conservation | N | L |

| Municipality of Hybe | Public administration | PU | Forest and natural resource management | L | L |

| Land and Forestry Department | Public administration | PU | Forestry service/ Forest and natural resource management/ | R | L |

| Tourists/Cyclists | Recreational users | PR | Tourism | R | L |

| Environmental activists/organizations | Civil society actors | C | Nature conservation | R-N | H |

| Customers | Recreational users | PR | Users of forest production ecosystem services | R-N | M |

| National Forest Centre Zvolen | Protected areas organizations | PU | Forest and natural resource management/ Research | N | M |

2.3 Reflection: overall governance situation before workshop

The stakeholder network in Czechia and Slovakia IR in a long-term remained relatively stable. In case of forest common Hybe (SK) the network contains of local citizens and municipalities, National Park “Low Tatra Mountains”, environmental NGOs and activists, district office (Land and forestry department), game hunters, tourist (summers’ and winters’ ones). In case of Čmelak (Czechia) the network includes previously mentioned forest expert, volunteers, game hunters and private donors and sponsors (those who bought the certificates of the New Virgin Forest). In both countries, IR registered conflicts with the legislation (wood removal/retention requirement) and conflict with the game hunters (mainly in the Czechia) and this problems still exists – the legislation didn’t changed so far. The most important change in both cases is decreasing income. This could be seen as one of the most important factors fostering the individual will to change forest management in more innovative ways.

After the 2018 the main changes can be seen in broadening the stakeholder networks. During the InnoForESt activities, communication in Hybe expanded to include old members or nature protection authorities. During the workshops in Čmelak (roundtable, second CINA workshop) it was managed to bring together stakeholders that haven’t been able to meet before. Their interest to participate and discuss the factors and scenarios was partly done due to the bark beetle calamity and generally poor conditions of forests in country and their need to address current problems.

The 2nd CINA workshop on prototype development and discussion on different scenarios show the potential way in future development for Čmelak and other stakeholders / forest owners. Common discussion about scenarios and factors shows the importance of addressing the problem of overpopulated game and the need to protect new seedlings (damaged by overpopulated games, which is not effective covered by legislation) but also the possibility to compensate forests owners by public/regulatory compensations for more provision of FES (than wood production).

3 Overall approach

3.1 Innovation strategy of the case study

Because of very likely decrease of timber production in next decades due to increased calamity logging in recent years, Members of Forest commons in Urbar Hybe are aware of that they have to change their traditional approach to forest management (oriented mainly on wood production and profit maximization) and that they have to continue with innovative approaches they started to implement several years ago, such as higher diversity of tree species, natural forest regeneration, organic matter left on the soil, and selective cutting. Nevertheless, this will be a joint decision of the whole community of forest owners. Čmelak is in recent years also facing the decrease of revenue (because of declining sales of “certificate of patronage” and less resources from public grants), so they are open to implement innovations in forestry management which will bring both: additional financial resources and improvement and intensification of forest ecosystem services provision.

All innovation activities are rather open-ended according to the possibilities of expansion of new forest management practices to new lands and to find new ways of their financing (based on payments for ecosystem services). Representatives of both forest communities are considering further actions and development and they are open to new ideas.

We organized workshops (e.g. the workshop in 1 October, 2019) where a broad range of stakeholders was sitting around one table. Without these events, they would not meet for such collective discussions. Some of them are also still in individual bilateral contact. At the end of the workshop, many of the stakeholders asked us, if we will continue in organizing such events. We are now preparing a follow-up discussion/workshop (most probably in February 2020) where we will continue with a more intensive discussion about the future of forest management in the region.

3.2 Platform and network process

The following list presents the key interactions with the local stakeholders and meetings of IR team where the further development of both collective actions was discussed:

- Collective Governance of Ecosystem Services Slovakia/Czech Republic: Introductory meeting (Prague – CZ, 15-16 December 2017)

- 1st InnoForESt CINA workshop: Innovations in Forestry: Forest commons Hybe (Hybe – SK, 3 July 2018)

- Focus group/round-table discussion with Čmelak 1 (Liberec – CZ, 11 July 2018)

- Collective Governance of Ecosystem Services Slovakia/Czech Republic: Stakeholder analysis (Prague – CZ, 25-6 September 2018)

- Collective Governance of Ecosystem Services Slovakia/Czech Republic: Governance assessment (Prague – CZ, 28 November 2018)

- Focus group Čmelak 2 (Liberec – CZ, 10 January 2019)

- Collective Governance of Ecosystem Services Slovakia/Czech Republic: Scenarios (Prague – CZ, 16 January 2019)

- Collective Governance of Ecosystem Services Slovakia/Czech Republic: Role Board Game Adaptation (Prague – CZ, 8 March 2019)

- Meeting with a key representative of Čmelak: pre-discussion of scenarios, organization of the 2nd CINA workshop (Liberec, the Czech Republic, 3 July 2019)

- Interviews with individual stakeholders in Hybe about concrete innovation factors by CETIP team members – SETFIS interview about key influencing factors, (Slovakia, August 2019)

- Interview with stakeholder in Liberec (forest expert and forest manager of Čmelak’s forests) – key influencing innovation factors (Liberec, Czech Republic, 26 September, 2019)

- 2nd InnoForESt CINA workshop in Liberec, (Liberec, Czech Republic, 1 October, 2019)

- Meeting with a key representative of Čmelak: organization of the “Czech-German” field IR field trip; organization of next workshop with stakeholders (Liberec, Czech Republic, 5 December, 2019)

- Discussion seminar with broader (expert) public “Forests in time of Climate change” (Liberec, Czech Republic, 22 January, 2020)

- Planned activities:

- 3rd CINA Workshop: Prototype assessment and road mapping

Several smaller meetings/skype or phone calls were organized to prepare the 1st CINA workshop held in Hybe and the round-table (focus group) in Čmelak (not all of them are listed above). The aim of those first meetings was to know each other (IREAS, CETIP, Čmelak, Hybe), gain knowledge about history of both forest commons and to identify key actors in innovation process (directly and indirectly involved).

In the meantime, between the two CINA workshops, several intensive meetings between IREAS, as a representative of the IR, and CETIP, as a scientific partner, were organized to discuss the stakeholders and governance analysis. At the same time, in cooperation with people from Čmelak and Hybe the historical timelines of both forest collective actions were developed. In close collaboration between IR and science partners the main obstacles and barriers for innovation development were identified and further analyzed. The goal of those activities was to have materials for developing innovation scenarios and gain inputs for adapting the RBG.

The 1st CINA workshop and round-table was also necessary for the identification of key barriers and motivation factors, which together with the SETFIS factors allow us to prepare inputs for the discussion on the 2nd CINA workshop among others stakeholders. The lively character of the discussion on factors was the indication that they are also very important for innovation prototyping and not only the discussion of different scenarios itself. It shows, that lot of stakeholders share the same problems (bark beetle, drought, overpopulated game, financial problems etc.) and that these problems also affect both the discussion about the scenarios and establishing of new scenario/prototype as well as the discussion about next steps of stakeholders to make lobby group and to affect the national legislation.

3.3 Overall CINA workshop strategy

During the first workshop in Hybe (July 2018) and focus group in Čmelak (July 2018), the history of the innovation process was described and influential factors were identified. Also, perspectives on potential futures were discussed (threats, opportunities, ideas on new innovations). Based on these events, the first draft scenarios were created, which were afterwards discussed during other meetings with members of Čmelak. The aim for the 2nd CINA workshop was to very deeply discus factors and scenarios with wider range of stakeholders. About 20 stakeholders attended the CINA workshop. During the second CINA workshop (October 2019), this broad group of stakeholders selected the final set of ca. 10 most important factors and the scenarios were discussed. During the scenario discussion, some new ideas for readjustment of the scenarios have occurred, or we can say the first draft of prototype was proposed. The group of stakeholders agreed, that we (IREAS+CETIP) should organize another follow-up workshops and create a working group, which will help further develop and discuss a prototype, which will be most probably based mainly on scenario 1 (with possible involvement of elements from scenario 3). This prototype is a result of discussion not only about the draft of three scenarios, but also about the factors. Discussions showed that stakeholders want to address main issues and obstacles in the prototype development (overpopulated game and systematic financial compensations for provisioning of non-production forest functions for forest owners and managers).

The sequence of the workshops and meetings followed a logic structure: getting know each other (IREAS, CETIP, Hybe, Čmelak) ⇒ preparations for 1st CINA workshop ⇒ 1st CINA workshop ⇒ elaboration of outputs from 1st workshop (factors, barriers, stakeholder analysis etc.) ⇒ preparation of scenarios and adaptation of RBG ⇒ preparation for 2nd CINA workshop ⇒ 2nd CINA workshop (discussion of scenarios, prototype development, RBG). The aims and our assumptions from workshops are described in section 3.2.

4 Type 1 workshop(s): Innovation analysis and visioning

4.1 Visioning workshop 1

4.1.1 Scenarios used

The 1st CINA workshop in Hybe (SK) (Urbar Hybe, 2018) and related round table dicsussion (focus group) in Liberec (CZ) (Čmelak, 2018) were used mainly for development of scenarios. Stakeholders identified key factors for development of innovation activities in their regions. Based on the workshops and further discussions with stakeholders three main possible ways of development were identified. Table 4 shows the first version of different possible scenarios which may be considered and which will be further discussed with stakeholders in both communities. These were developed as a response on the first workshop.

First scenario is based on state regulation, which is stressing the nature conservation goals (see Table 4). The communities of owners of the common forest would be compensated for loss of income due to implementation of nature conservation measures to achieve higher FES provision.

Market rules in combination with external certification authority (this authority is not connected with the forest owners) is the basic governance arrangement for the second scenario. Thanks to increasing environmental awareness and demand for local and regional products the local wood produced in a sustainable way will be sold to local market (chains) and used in local restaurants/hotels/public buildings. Within this scenario the value added of local wood (from environmental point of view, which can mean more money for sustainable forestry activities and support of local economy) will be key point. A trusted certification authority will guarantee the quality and local origin of the wood.

The third scenario is based on the payments for ecosystem services designed and managed by the community itself. It is based on the self-regulation (and monitoring)/self-governance of the community. In relation to the workshop (Urbar Hybe, 2018) and roundtable (Čmelak, 2018) the payment scheme can be based on a selling of carbon „indulgences“/offsets to compensate a carbon footprint in a way of certificates of CO2 compensations for tourist, local businesses (local entrepreneurs and firms), wide public or based on the idea of forest ecosystem services as a marketable goods in a way of continuous financial resources for wood chipping, planting new trees/forests, other carbon forestry technologies.

| Scenarios/Asp | Scenario 1: Regulatory (compensations) | Scenario 2: Local market (PES, certificates..) | Scenario 3: Hybrid ecosystem service governance (FES- community payments) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actor configuration | Forest owners, forest industry, recreation, nature conservation authority, municipality | Forest owners, forest (and timber) industry, recreation, nature conservation authority, municipality, local market chains and networks | Forest owners, forest associations, nature conservation authority, municipality, recreation and citizens networks, |

| Governance arrangement | Regulatory rules (state, local authority) | Market rules + external authority (e.g. a certification committee which will guarantee the quality/regionalism of certificated goods and services – e.g. certificates for local wood) | Self-governance/self-regulation within the community (the community will determine the purpose of the payments, the price for the services and goods as well as the decision about planting/harvesting/implementation of carbon forestry technologies) |

| Organisational embedding | Ministry of Environment, Ministry of agriculture and Forestry | Forest owners, landowners unions, external certification committee | Forest associations (subject/agent which supply FES certificates) |

| Business model | State regulation: harvesting limits, stress on nature conservation, compensation for loss of income (because of FES provision), support of nature conservation | Profit growth/ marketing of added value of local wood => more money for sustainable forestry activities, support of local economy expected harvesting payments local wood certification for products with added value |

(Voluntary) payments to support long-term FES provision e.g. selling of carbon „indulgences“ – reduction of carbon footprint => selling certificates of CO2 reduction to tourist, local businesses, wide public FES as marketable good – continuous financial resources for wood chipping, planting new trees/forests, other carbon forestry technologies Self-regulation and monitoring |

| Role of citizenry | Citizens as members of forest cooperative and local community, enviro-activists and networks Because of regulation realized by public administration is the role of citizenry very limited | Common planting days (volunteers), users/ citizens Pushing on local public administration to use local wood (in schools, town hall etc.…) Citizen demand (= tourists) for tourism infrastructure equipped with products from local wood (hotels, restaurants, outdoor benches etc.) Customers of local companies – environmental awareness |

Citizens as members of forest cooperative and local community => collaborating on setting rules, enviro-activists and networks As buyers of CO2 indulgences Customers of local companies which are CO2 neutral – environmental awareness |

| Role of techn. & science | knowledge of ecosystem based solutions vs sectoral | Technology for sustainable forest management, Virtual marketing | Novel technology for FES sustainable provision, Marketing, evaluation + justification of environmental impacts, approaches for collective action |

| Discourse context | Lack of financing, legal, institutional misfit: Nature conservation vs forestry | Market price pressure to increase wood production, market competitiveness of local wood (less intensive harvesting/more expensive wood?) support of local economy |

Corporate social responsibility Carbon footprint |

| Key trends | Possible new regulations for EU on carbon targets growing environmental awareness | Possible new regulations for EU on carbon targets, stronger private governance and liberalization, incentives for low carbon (business) environments Rising of environmental awareness + rising demand for local/regional products |

Possible new regulations for EU on carbon targets, growing environmental awareness, biodiversity Collaborative approach for low carbon business model, effective ecosystem service governance Rising of environmental awareness |

| Uncertainties | Forest damages, real carbon storage, prevent the release of carbon (fires, harvesting etc.). | Demand side (for local timber), demand for certified local wood by local businesses | Demand for CO2 certificates and profitability of ES innovations real carbon storage |

| Future prospect | Lack of findings for state nature conservation regime | Market based PFES and regional goods Focus more on local/regional economy than on FES production |

Continuous payments for long term provision of FES regime based on the self-organization of the community Focus primarily on long-lasting FES provision |

4.1.2 Setting

The workshop was divided into the following sections:

- Introduction of the project, program and stakeholders – introduction of researchers, project logic and all participants and outline expected outcome from the discussion.

- Innovation process and its stages – stakeholders identified the key actors who were directly involved in the innovative process and those who have indirectly influenced it, they also identified important dates/milestones in development of their innovation activities.

- Identification of key issues for the innovation development – stakeholders identified key issues which represent barriers or obstacles for innovation development.

- Identification of key “motivation” factors for the innovation development – stakeholders examined the main “motivation” factors which influence the innovation development.

There was also a short excursion in surrounding forests managed by Forest commons Hybe.

After the workshop, the focus group (round table discussion) was conducted in Liberec with representatives of the Čmelak association. The focus group had exactly the same arrangements as the workshop and provided additional findings for future scenario development. Thus, the workshop contributed to the visioning and analysis of what was going to be the innovation prototype. The workshop was organized on 3 July 2018. The focus group was organized on 11 July 2018.

4.1.3 Participants

Mainly key stakeholders from Urbar Hybe were invited for the first workshop in Hybe and focus group in Liberec. There were rather internal actors who are working in innovation regions. In Hybe main managers from the forest commons Hybe participated together with invited external experts on the carbon forestry and researchers from CETIP and IREAS. In land Trust Čmelak only internal actors were invited. Both meetings were organized in rather smaller arrangements to have focused discussions: 10 participants in Hybe and 5 participants in Liberec.

4.1.4 Key thematic findings

Key findings form the workshop in Hybe (Urbar Hybe, 2018) and the Focus Group in Liberec (Čmelak, 2018) were used for mapping of historical development (see chapter 2.1) and the stakeholder analysis (see chapter 2.1).

In Urbar Hybe the forest community face to the challenge in relation to establishment of more effective communication between community members as well as with external actors, such as NGOs, National part, state institutions, etc. According to the leaders, there is needed a change in attitudes of members, mitigate conflicts among them and to enforce adaptation of forest management closer to carbon smart forestry. The reforestation of damaged forest results in young diverse forest not only spruce monoculture and increased a carbon sequestration. All the activities are aiming to increase forest resilience and well-being of the local community and other users of forest ecosystem services (opportunities for recreation) and contribution to climate change mitigation by carbon sequestration (Urbar Hybe, 2018).

In Čmelak, studied innovative activities towards more diversified New virgin forest are based on the sale of the certificates, cooperation with companies, public grants as well as voluntary work of association members. However, the financial sources from selling certificates (used for buying new land) is decreasing, as well as money from public grants (used for forest management activities). In the beginning public expressed positive interest (public money collection, certificates, volunteers), but innovation doesn’t currently attract new buyers. Buyers bought the certificates mostly only one time, they do not buy it again/repeatedly, thus it is only one-off source of money (as described in section 1.2). In these days it seems, that most of the potential buyers have bought the certificates, number of new buyers is decreasing. Therefore, Čmelak is looking for some new product/innovation which will bring continuous sources of money (Čmelak, 2018). Possibilities are to stimulate legislative changes: non-productive ecosystem services should be more supported by the legislation (e.g. government-paid PES). Stakeholders’ common interest is to establish a working group, which will prepare materials for legislative change and lobby for that. They are also thinking about new types of certification, such as for CO2 compensation. In the past few months before writing, Čmelak has intensified its PR activities (new website, Facebook etc.) and developed new project/campaigns (not all of which are directly related to forests). For more details see chapter 4.1.1 Scenario used in CINA workshops.

In both communities there is income stagnation these days and leaders of both communities are searching for new opportunities to finance their innovative activities. So far, innovative activities are not really based on any policy instruments and they are based on the (voluntary) activities of the community members and management. From this point of view, our experience is, that sustainable (innovative) forestry management in common forests is possible without any governmental interventions, but it is time demanding and it needs much of enthusiasm and effort by members of the communities. On the other hand, the stakeholders from our IR agreed, that for faster innovations implementation on a larger scale (in terms of new PES schemes, more focusing on non-provisioning FES) of governmental interventions would be useful (e. g. governmental subsidies for particular forest management activities), but the stakeholders from IR should be involved in designing the governmental intervention.

Activities are partly perceived as negative by some groups of stakeholders. For, example the president of the land trust Čmelak is an important local politician and due to the connection with his public function some activities are seen in negative light (this is supported mainly by opposition). In Urbar Hybe some forestry activities after natural disturbances are seen as problematic by the environmental NGOs because of the extensive calamity harvesting in National Park and slow reforestation after calamity due to natural reforestation (which is more time consuming) – see also section 2.1.

4.1.5 Detailed thematic findings

Participants of the workshop consider as innovation the self-organization of their community and their ability to adapt to several social and natural disturbances that are happening in forest management due to the new legislation and forest calamities.

Despite the fact that self-organizing forest management communities already exist for quite a long time , their flexibility to respond to new challenges it is still an innovative forest management model in the Czech-Slovak context. It can respond more flexibly to new challenges. We have the experience that the majority forest owner (in CZ as well as in SK the state owns more than 50 % of forests) does not respond so flexibly and does not take into account the needs of the local community (non-productive FES provision). Connection with the needs of community living in neighborhood to the forest (FES provision) as well as the flexibility and readiness for actions are of the most important innovative issues self-organized communities in forestry sector.

Internal structure: This forest community is successful because of their special internal sophisticated structure consisted from General Assembly, Committee and Supervisory Board that is not usual for other forest communities. The reason behind is that people in this community simple had / have the courage and willingness to work.

Process of selling the wood: This community is also particularly innovative because they own their own expedition warehouse and sawmill allowing them to sell wood for better price in the market comparing to the other forest communities that sell wood directly in the forest where it is cut down.

The fastest response to disturbances: The community was the first one from the groups of forest owners/managers in the fallen forests area that took the action and actively started to fight against natural disturbances – strong windstorm followed by beetle infestation (Ips typographus and Hylobius abietis). This action saved some of their economical returns. However, because of late response of neighboring forest areas, this community also have to face the bark beetle infestation spreading to their health forests from surrounding infected forests.

Certification and its threat: This community also got the PEFC certificate for sustainable forestry as one of the first forest communities in Slovakia (in the year 2008). However, above described natural disturbances have caused that community cannot sell certified wood anymore. They have to do only calamity logging in next few years due to the extensive damages caused by wind storms and bark beetle. They are worried how the economic situation of the community will change because calamity wood can be sold only for lower prices.

The deterioration of economic prospects also causes internal conflict between the approximately 1000 community members. Most members expect continuous reimbursement for their shares in spite of difficulties to sustain forest community revenues after natural disturbances and funds required for forest regeneration.

Conflicting legislation: National legislation in Slovakia complicates the forest community’s management and recovery from natural disturbances. Two laws that foresters have to follow are in conflict (see also section 2.2). While the Forest law requires the removal of deadwood from the forest, Nature Protection law prohibits such removal without a permission process, especially now that part of this forest community’s forests are located in a National Park. For example diversified environmental NGOs can freely enter into this process (citizens’ initiatives, activists) and has the right to argue why not to permit the removal of deadwood. This is the big issue for this community because civil initiatives postponed the permission process and bark beetle spread even wider to healthy forests. (This community is the only one with a hunting area, which makes this community lucrative.)

Possible solution – carbon management practice in future?: Participants of Focus Group can see possible solution in forest management adaptation to more carbon forest management but firstly they have to stabilize forests after natural disturbances and secondly there is the question of financial support to do such type of management.

The community uses horses, cable yarding or tractors for timber skidding for years. These mechanisms compared to heavy harvester causing less carbon losses. Community also applied selective cutting instead of clear cuts. However, it is not possible anymore because of natural disturbances. Today, they started to spread natural regeneration of forests and participants of focus group expressed the willingness to apply another management practice of carbon forestry – leaving biomass in forest to cover soil and thus minimize carbon losses. However, the most effective way to realize this practice would be to make chips from left branches by machine and then put chips back to the forest on the soil. It would be beneficial for foresters because weeds would not grow so much, soil would stay moist and fertile as well as for global goal to keep carbon in the soil. But proper technology is necessary for this management practice and it costs too much money for such small community. However, if there is the payment mechanism for such ecosystem service provision they see it as a great solution. They see no problem if they would receive money from state and pay this money to the private owner of chipper for taking branches from forest, making chips and returning them back to the forest. Participants of Focus Group are open to collaborate because they think that knowledge sharing and cooperation across the sectors is important for community well-being.

A: Innovation process and its stages

Together with stakeholders we have identified the whole innovation process, in particular key milestones and key actors involved. Stakeholders described in detail the story of their innovative activities. This part of the workshop addressed questions:

- What is the innovative process? Which are key innovative activities? When your innovation started? Who was the key actor at a particular stage?

- Are there any policy instruments currently used (or associated with) the innovation? Which are they and how they work?

- What are the main outcomes/(expected) impacts of your innovation? Has the innovation so far produced any unintended side effects?

These discussions contributed to the creation of the innovations timelines (see chapter 2.1.) and identification of key stakeholders (see chapter 2.2.). The results at the workshop (Hybe, 2018) and focus group (Liberec, 2018) were originally created in form of timelines developed by stakeholders (see Figures 1-3).

B: Identification of key issues for the innovation development

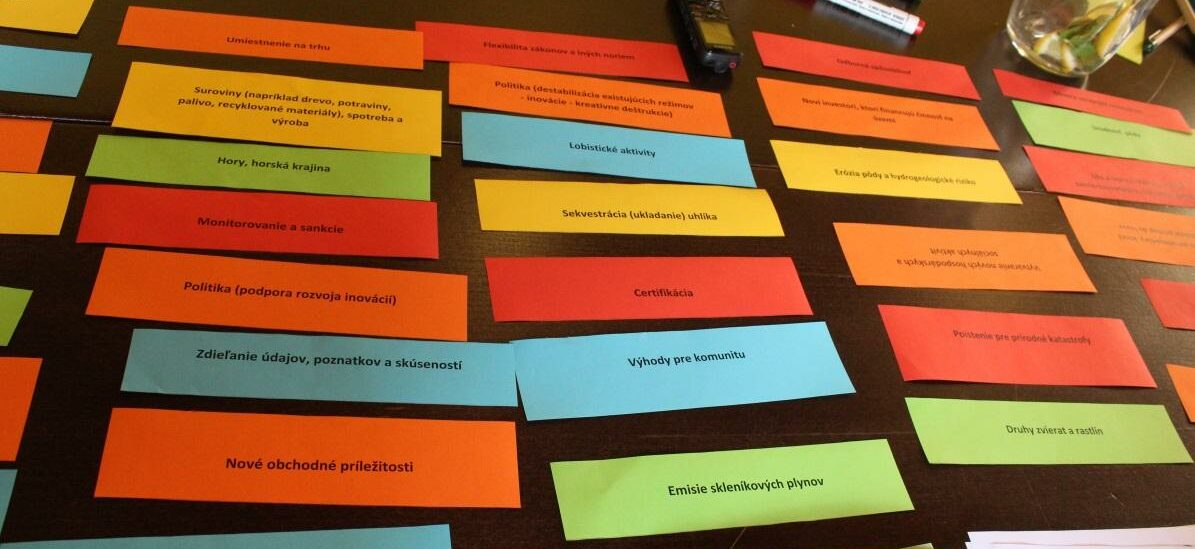

The aim of this activity was to identify key issues which represent barriers or obstacles for innovation development. Stakeholders could individually write maximally 6 critical issues (barriers or obstacles) for their innovations – each issue per one coloured post-it. All notes were collected and clustered on a board/large paper (Figure 4). Stakeholders later discussed about each topic/cluster to address following questions:

- Which past/current issues could be seen as barriers or obstacles that needed/need to be tackled for innovation development?

- How do you deal with these issues? How you can overcome these issues?

Stakeholders discuss and explained which are the most critical for the innovation development. They mentioned a problem with land accessibility as one of the most important as it connects many related issues. mentioned that forest management is easier in part of forests that are closer to the village. Forests in this part are easier to access as well as to transport timber. Moreover, less restrictions of nature conservation are in this area that makes forest management less complicated. On the contrary, remoted forests are poorly accessible and horses are the most suitable to use for timber transport. In addition, mountain terrain causes the problems for transport of the timber from the forests and wood processing. At the same time, there are also problems to build new roads in the forest (for harvesting as well as for fire protection) due to strict nature conservation restrictions. There is the conflict between our community and tourists as well as cyclists. As the community members built up the roads for vehicles to be able to access forest to manage which is not primary intended for the tourists/cyclists but at the end they are the main users who to some extend limits work of forest commons members and who leave their garbage there (in Slovakia everybody can access forest regardless of who owns it.). However, if the aim of nature conservation will be achieved and 25% of our forests will be in untouched zone, it means not only restrictions in forest management for our community but also tourists and cyclists access to this part of forests will be prohibited.

Participants discussed also general issues related to the limited infrastructure, e.g. limited internet connection and poor telephone signal, or to the out migration and aging population in the region which may limit innovation potential.

Another issue is decreasing income from the forestry in future. So it seems that people do not care how much they will receive from forest community income coming from sold timber. However, most of members do not realize that the period of receiving income from mining will rapidly decrease in next five years (because of natural disturbances). According to the workshop participants, it will be necessary to reassess the whole structure of the community.

There was also mentioned a conflict between Urbar Hybe and nature protectionists (environmental NGOs), even if they see that they have many common interests and goals. Participants of Focus Group admit that the environmental NGOs is so successful in activism of entering into the forest management process permission because their campaign to protect nature/forests was great. Participants also admit they should promote community´s goals, activities, values, etc. better and make their vision more visible.

Some participants think that there are problematic, non-functional and low financial compensations, because of the conflicts with nature conservation. They see possible opportunity in applying of EU funds, however other participants were sceptical as they think that compensations just simply do not work in Slovakia.

Within the Czech focus group same activity was held to identify key issues and obstacles. The biggest issue for Čmelak was conflict with Municipality with extended power (extended competences, delegated act on behalf of state government) – department of hunting protection (on behalf of state government; State administration of hunting; same officials as in the department of forest protection).

Local hunters have lodge a complaint on behalf of this department to remove a fence (five hectares of fenced area protected the plant from over-populated game), because it impede the movement of game. Building Authority concurred with this argument (“fence has interfered in good welfare of game”). Therefore the fence should be removed, at Čmelak own expenses. Act (no. 289/1995 Coll., section 32, article 7) “it is forbidden to fence the forest for reasons of ownership or to restrict the general use of the forest, this does not apply to forest nurseries, fencing to protect forests against game and fencing the game preserve.” It is also forbidden to make constructions in the forest. The hunters were claiming that the fence hinders hunting (that was their main motivation). They wanted to remove the fence. One of the way, how to remove it, was to label the fence as a construction (which is forbidden in the forest). So officially was this legal controversy mainly about form of the fence – the dispute about it is or it is not a construction (under Construction law). Department of hunting protection maintained that this fence is a construction, which is in the forest forbidden. Within a conflict of interest the Department of hunting protection is biased in favour of local hunters.

Second biggest issue for Land Trust Cmelak is decreasing income. The main innovative activity is PES scheme based on the sale of the certificates for establishing ‘New Virgin Forest’. These sources of income have been on decreasing trend. The main reason is that certificates are based on a one-off payment basis instead of periodic payments.

C: Identification of key “motivation” factors for the innovation development

The aim of this activity was to examine the main “motivation” factors which influence the innovation development. Stakeholders were dealing with the following questions:

- Which are the key “motivation” factors for the innovation development?

- Why they are important? How they influence the innovation activities?

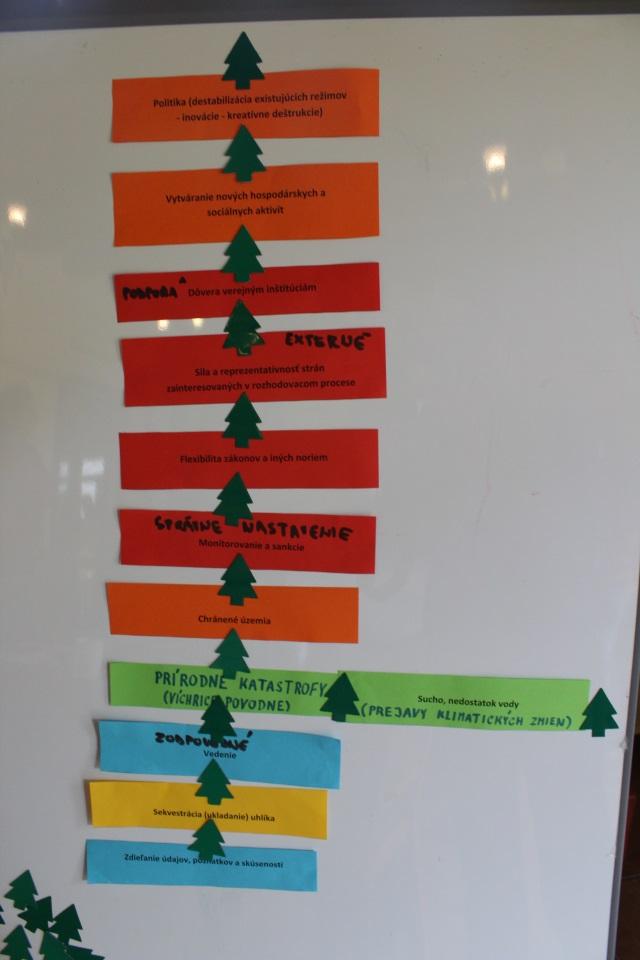

A list of different possible factors was prepared in advance (Annex I) and participants selected from the list of different factors those which are seen as the most important for their innovations (Figure 5). Stakeholders could identify their own factors besides the list or modify factors from the list. Final selection (Figure 6) of 8-10 most important factors was discussed into the detail in relation to the importance of particular factors and to the way in which they influence innovative activities in IR.

- Policy (Destabilising existing regimes-innovations- creative destruction),

- Protected nature areas,

- Creating new economic and social activities,

- Climate change (drought, lack of water),

- Flexibility of Institutions for transition (laws and norms),

- Opportunities for carbon sequestration,

- Exchange of information and knowledge

Redefined factors:

- The strength and representativeness of the stakeholders in the decision-making process,

- Support from and trust in public institutions,

- Monitoring and sanctioning (with correct/right settings),

- Responsible management/leadership,

New factors:

- Natural disturbances (storms, winds, …)

Among the key factors affecting the development of innovative region in Czech part of the IR are:

- Protected areas

- Biodiversity conservation

- Environmental awareness

- Monocultures and decreasing area adaptability

- New investors, financial sources

- Policy (Destabilizing existing regimes – bias in favor of hunters),

Subsequent discussion about key factors showed, that protected areas (Natura2000) was the initial factor for the transition from single crops to mixed stands. Čmelak requested the Natura 2000 to extend nearby protected area to Čmelak’s parcels respectively. This action helps with receiving grants. Biodiversity conservation and environmental awareness are the main internal factors which motivate Čmelak’s founders, members, employees and volunteers. Major objective of Čmelak activities is the biodiversity conservation in order to increase the area adaptability. Positive effects of new investors and financial sources allow to continuing and to further develop both activities, restoration of monocultures and expansion of owned land. On the contrary, the policy regime and its bias favoring hunters is a factor with a negative impact on innovation activities.

4.1.6 Process

The workshop was well prepared in advance and there was clear logic of particular activities. Activities were designed to promote discussion among participants. Rather smaller arrangement enabled to gain knowledge from each participant and everyone had opportunity to express his/her opinion. There was no deviation from the plan (expect three participants apologized for absence just before the start of the workshop). There was very pleasant and stimulating atmosphere which lead to very interesting proposals (such as promotion of wood chopping). We plan to keep our workshops in this rather smaller arrangements, although in extended range of stakeholders (up to 20 participants).

When the discussion was going to be rather general, our moderator (Tatiana Kluvánková) was able to quickly get it back to the track. The choice of this moderator/facilitator seems to be important because she is well known in the community but at the same time she is external expert. In addition, she is well oriented in the InnoForESt project.

4.1.7 Stakeholder interactions

In both, the workshop in Hybe and focus group in Liberec there was rather homogeneous constellation of stakeholders. It was evident that all of them were aware of actual challenges of forest commons – Urbar Hybe and Land Trust Čmelak and they follow the same objectives. There were no conflicting situations among stakeholders. The discussion was very open and even if there was not always consensus among all actors there were able to handle with it without any conflict.

4.1.8 Lessons learnt

The workshop and particular examinations were well prepared which enabled fruitful discussion about the current situation and future perspectives. The discussion with local participants resulted in identification of key internal and external actors important for development of innovations. They also identified the key stakeholders which influence their current innovative activities. Research team plans to include wider spectrum of stakeholder in future workshops.

There was an agreement on continuing collaboration in relation to develop innovative solutions to identified issues. Representatives of Forest commons Hybe expresses their willingness to adopt some novel practices (e.g. wood chopping) towards SMART carbon forestry. We also agreed on future individual interviews and development of potential scenarios and organization of other workshops.

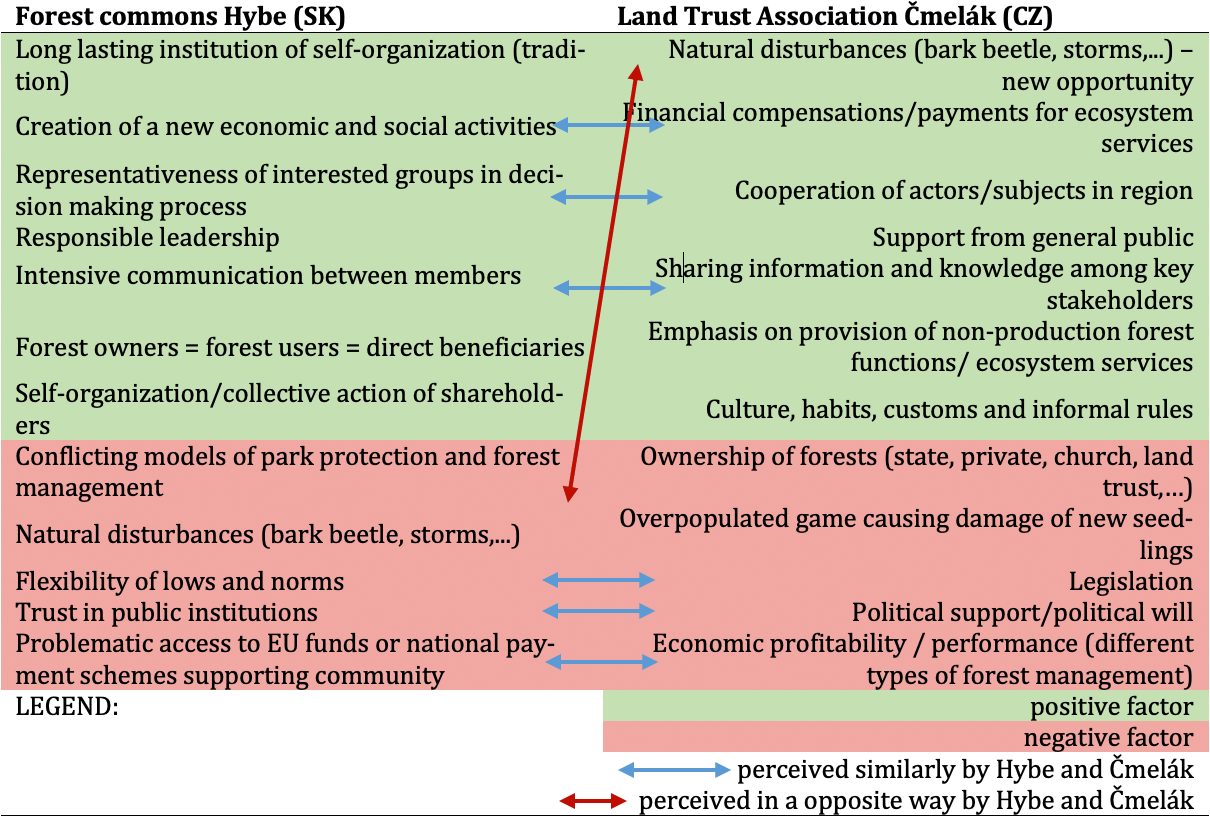

4.1.9 Reflection: factor reconfiguration

The first set of factors was created before the first CINA workshop in HYBE based on our expert knowledge. Set of factors consist of almost 40 factors. Key “motivation” factors were identified by stakeholders during the workshop and the focus group and some missing factors were added. These identified factors created the fundament for the scenario development and further prototype development:

- Policy (Destabilising existing regimes-innovations – creative destruction),

- Protected areas,

- Creating new economic and social activities

- Climate change (drought, lack of water),

- Flexibility of Institutions for transition (laws and norms),

- Carbon sequestration,

- Exchange of information and knowledge

Among factors redefined or added are:

- The strength and representativeness of the stakeholders in the decision-making process,

- Support and trust form public institutions,

- Monitoring and sanctioning (with correct/right settings),

- Responsible management/leadership,

- Natural disturbances (storms, winds, …).

This set of factors was further revised due to the SEFTIS analysis. For final identification of ca. 10 most influencing factors (discussed by broader range of stakeholders), another discussion of factors for the 2nd CINA workshop was prepared.

4.1.10 Reflection: governance modes

During the workshop these factors were discussed in relation to the designing of the general role board game concept and scenarios. Especially, different governance modes of ecosystem provision were discussed: state compensation, self-organization, private payment schemes. Based on the discussion in Hybe a first concept of the role board game was designed and later presented during General Assembly in Trento. Afterwards discussion in our team takes those factors and RBG design also into account when developing three possible scenarios. The discussion about scenarios was held in Liberec with the key representatives of Čmelak before the 2nd CINA workshop. Representatives of Čmelak expressed more or less interest in all of three scenarios but mostly to the scenario 3 – private payment scheme (CO2 indulgences/offsets). They did not reject any of them. During the discussion with Čmelak some opportunities for the implementation of scenario 3 were discussed.

5 Type 2 workshop(s): Prototype development workshop

5.1.1 Scenarios used

The scenarios were developed based on the outputs from the first workshop and focus group. After some partial discussion with some stakeholders they were developed further and text parts were prepared. They were changed into a shortened text and were presented to stakeholders during the workshop. In response to the discussion during the second workshop, the scenarios were adjusted and they will be further discussed in future.

Scenario 1: State compensation for economical management

The first scenario develops the idea of the state support to all forest land owners – it sets up a governmental compensation scheme to meet Czech/European nature conservation or climate regulation goals. The aim of compensations is to increase provision of non-production FES.

The first scenario depends primarily on the amendment of legislation and the introduction of compensatory fees for sustainable forest management supporting the provision of non-productive FES. The compensation fees will be paid by local or national government or other institutions of public administration, possible even by EU-Funds, e.g. Common Agricultural Policy. A prerequisite is the valuation of the cost of environmentally friendly methods, practices and forest management techniques, as well as the values of non-production functions of the forest / ecosystem services that will be supported through the application of these practices. In this case/scenario the valuation should be done by independent experts following a transparent methodology, because public money will be spent (in the other two scenarios the valuation will be useful as well, but not necessary. At least not necessary done by independent expert, because the payment for FES will be determined on the market) Payments could be based on clear demonstration of a positive impact (in measurable units) on the production of ecosystem services (this option is preferred) or on lost profit for “inactivity” (reduced logging) and reduced timber production. Some of the stakeholders, who were present on the second CINA workshop, came with an idea, all forest owners should become some universal and regular payments (from government), because they are already providing many FES to the society without any compensation. They suggested similar payments as the farmers receive (something like SAPS – single area payment schemes). However, after long discussion the stakeholders agreed, the compensation should be conditional on specific practices / activities leading to nature-friendly forestry and not paid across the board.

This option would support the conservation of nature, FES provision and the promotion of biodiversity in forest ecosystems, and by economic incentives would motivate forest owners to conserve their management in a way that does not reduce their profits. Research institutions would also play an important role here, aiming to reward ecosystem services and lost profits and set up a compensation mechanism.

To implement this scenario in practice, amendment of legislation is needed. During the second CINA workshop it was agreed, that a special working group will be established. This working group will further discuss possible legislative amendments, prepare some suggestions for these amendments and lobby for it. Establishing and activities of this working group are part or the scenario 1.

Scenario 2: Local Resources – Local Economy – Local and Global Benefits

The second scenario is based on value added of the local wood on local/regional market. It is expected a creation of a local certification provided by a trusted certification authority which will connect local wood producers with local/regional customers, restaurants/hotels/public administration. The certificated will be issued only in relation to the certain sustainable management of the forest reflecting the non-production FES.

Greater involvement of regional firms and actors in the forestry – wood product value chain. It uses the support of the local economy and the willingness to pay for regional but more environmentally sustainable products. There is a growing demand for local products in the region. This is especially true for food, but why not apply this principle to wood products. This wood from sustainably managed forests can be more expensive than conventional wood, but forests can provide more non-production functions in a given area and, moreover, reduce the negative impact of transport. Wood from such a forest is certified by a recognized authority (regional wood from sustainable management) and the buyer thus supports the provision of forest ecosystem services and environmental protection in their region.

This scenario was inspired by the practice of the Austrian Eisenwurzen, where typical buyers include local governments, designers or companies. Town halls furnish regional wood with furniture, designers work with local wood, and competitions are held in the region under the auspices of a local art school. They all show their environmental awareness, local authorities and local governments set an example for citizens and support the development of the local economy. The region also attracts tourists who can stay in certified log cabins and stay in the countryside. In essence, it is about giving wood its own story and thus greater economic added value.

In this option, the demand for sustainably produced regional timber and the provision of a certifying / umbrella body are essential. Currently, this scenario seems not to so attractive for the stakeholders. Maybe is too complicated to (artificially) start a new market and find a certification authority. During the second CINA workshop, this scenario was not directly excluded by the participant, but there were not much enthusiasm to discuss it or develop further. The participants were much more interested in the other two scenarios. Another possible reason, why (in the workshop participating) stakeholders were not so much interested in this scenario may be, that nobody (except of forest owners) from the potential wood product value chain did not participate in the workshop.

Scenario 3: Payments for forest ecosystem services

The third scenario develops the payments for ecosystem services designed and managed by the community itself. It is expected to have the payment scheme based on a selling of carbon offsets to reduce a carbon footprint in a way of certificates of CO2 reduction for tourist, local businesses, wide public or based on the idea of forest ecosystem services as a marketable goods in a way of continuous financial resources for wood chipping, planting new trees/forests, other carbon forestry technologies. Voluntary ecosystem payment instruments can be used as a long-term (recurring) source of finance for innovative forestry approaches. Users of ecosystem services (residents, businesses, tourists, etc.) will pay voluntarily (e.g. by purchasing certificates) for the provision of ecosystem services.

One option is certificates for the provision of forest ecosystem services linked to the carbon cycle. CO2 emissions are a socially resonating issue. Many businesses and people want to be “carbon neutral”. Charged ecosystem services in the case of innovative and sustainable forestry (gentle logging – horses, mixed forest planting, reduced timber production, forest expansion, selective logging, chipping, etc.) may be, for example, carbon storage and selling so-called CO2 indulgences/offsets. To do this, a CO2 calculator is available, which is able to calculate the carbon footprint of a person / company, etc. For simplicity, the equivalent of payment is the cost of planting new trees that are able to capture the same amount of CO2 per year (adult). People from Čmelak believe, that in the region will be a demand for such kind of certificates. Good marketing needed. An alternative tradable function may be to promote biodiversity, which Čmelák now sells in the form of its New Forest patronage certificates. However, payments would again be made on an annual basis in the form of carbon offsets.

This scenario can also be used in the local economy, where these carbon offsets would be bought by local firms that present themselves as carbon neutral. A typical example is a pizzeria with home delivery or other delivery. This carbon capture service would go through the market and the customer would decide whether to order food imports from a responsible carbon neutral company or a cheaper company but with a higher environmental impact.The sources of financing for these forests may also be payments from companies from other regions, which also present themselves in terms of environmental friendliness. The web interface would combine demand (eco-friendly companies that want to plant trees and reduce carbon footprint, promote biodiversity, etc.) and supply (forest owners who have the resources to plant new forests. Again, the price of this forgiveness should be “market-driven”). therefore, it should include not only the price per seedlings, but also the costs of aftercare or the purchase of land for planting.

In general, this scenario means an extension of current practices of Čmelak. They are already selling certificates (focused on biodiversity only), but they are usually purchased only once by each customer. The goal of this scenario is to find from financial point of view a sustainable source of money to extent the innovative forestry practices of Čmelak. Advantage of these kind of financial resources is, that the community could decide itself about the use of money and they are not restricted by rules given by the subsidy provider. Typically, is this money used for purchase of land, which is not possible to pay from subsidies or grants. On the other hand, Čmelak and other stakeholder are aware, that using only this scenario/payment mechanism will not enough for the innovative practices in larger scale. That’s why it should be combined with other scenarios.

5.1.2 Setting

The workshop was divided into the following sections:

- Short introduction of the project to stakeholders – introduction of researchers, project logic and all participants and outline expected outcome from the discussion.

- Simulation of decision taking in form of two treatments of InnoForEst Role Board Game – stakeholders were divided into two groups and discuss about different factors influencing the forest management.

- Focus group after the game with exercise for selection of the most influencing factors for the innovations in forestry in Liberec region with the focus on Čmelak’s activities – Stakeholders selected 11 key factors and weighted them based on their importance (positive/negative).

- Introduction of the project to stakeholders (some new came only for the afternoon part) – brief introduction of researchers, project logic and outline expected outcome from the discussion, the emphases were put on introduction of the other InnoForESt innovation regions.

- Introduction to activities of Čmelak with the focus on their financial aspects + historical overview.

- Introduction of scenarios and discussion about barriers and opportunities for the development of innovative activities in the region and potential for following innovative approaches from abroad. Summary of the results and wrap up.

5.1.3 Participants

The workshop was attend by diversified groups of actors. There were key persons from Čmelak civic association (director, former director, and key employees), volunteers, there were also forest managers and experts (state/private), private forest owners, representatives of state forests, local and regional politicians and representatives of academia. In total there were 18 stakeholders from the region and 9 representatives of InnoForESt partners.

The participants form Čmelak represented the regional forest management innovators. They have implementing innovations since more than 15 years and they are also a key partner in the innovation region for the Innoforest project. Their agenda was to present to other stakeholders their activities and visions for future as well as discuss the possible ways for change of forest management in the whole region with other participants. The representatives of state forests presented and discussed the position of the largest forest owner in the region and country (more than 50 % of forests are still owned and managed by state). All forest owners in Czech Republic should have a forest expert who helps them with forest management. Small forest owners (less than 50 ha) should have access to an expert paid by the state. The participating forest expert works as an expert for several small forest owners (including Čmelak, municipalities, other private forest owner). He is very innovative and open for “alternative” forest management (which far not the case of all such forest expert). He wants to support new ways of forest management in the region. Small private owners (incl. municipalities) are also often more open to innovation. Especially municipalities are often focused on non-production FES. During the workshop, they discussed their point of view on the topic.

Many participants of the workshop they knew each other, but were not in regular contact. Some conflicts have arisen between the representatives of state forest and other participants. The state forest oriented purely on production of wood and they are not very open to innovations. But they agreed, a follow-up discussion/workshop is needed, especially to discuss the current situation in forest strongly affected by climate change/bark beetle calamity.

5.1.4 Key thematic findings

Results from the RBG show that all key actors have very pro-environmental behavior and that it is quite easy to find a common strategy even if it is costly sometime. Based on the discussion during the RBGs it is clear that biodiversity and nature conservation is one of the key aspects for individual decision taking. Discussions also revealed some key leaders of the innovations who are influencing others. There is very important tandem of former director of Čmelak and their forest managers/experts who are very active in developing new ideas for the future development. Among other important are stakeholders a current director of Čmelak should be mentioned and regional politician/expert from academia.

Key finding from the CINA workshop 2 is the identification of the 10 key influencing factors. Key influencing factors were highlighted based on the discussion and individual assessment provided by each stakeholder. Key aspects of the Čmelák’s are the emphasis on provision of non-production forest functions/ ecosystem services and different ways of financial compensations/payments for ecosystem services.

Very important factor for the success of the innovative activities is the cooperation among actors from the regions (NGOs, forest owners and managers, local/regional politicians and administration) which is connected with the need of sharing information and knowledge among key stakeholders.