D5.5: Ecosystems Service Governance Navigator & Manual for its Use

| Work package | WP5 Innovation process integration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deliverable nature | Report (R) | |||

| Dissemination level (Confidentiality) | Public (PU) | |||

| Estimated indicated person-months | 5 | |||

| Date of delivery | Contractual | 31 December 2020 | Actual | 31 December 2020 |

| Version | 1.0 | |||

| Total number of pages | ||||

| Keywords | Forest Ecosystem Governance Innovation, SETFIS, Biophysical mapping, Governance Situation Assessment, Stakeholder Analysis, Constructive Innovation Assessment, Role Board Games | |||

Executive summary

We aim for the Navigator to be a practical tool that should help finding orientation and direction for (forest) ecosystem innovation processes. To that end we provide suggestions for practical application throughout most of the sections.

Deliverable 5.5 presents a Navigator to be used as a guidance to improve understanding on Forest Ecosystem Services governance innovations. The Navigator comprises the InnoForESt approach, as it has emerged in the course of this innovation action project. The Navigator entails a compendium of “heuristics” understood as a set of practical tools (rooted in theory) integrating the project knowledge generation and communication approach to forest ecosystem services (project glossary, analytical framework, fact sheets, typologies, workshops, etc.). It aims at giving orientation, not setting hard rules. The Navigator dedicated to the interested public outside this project for a first impression of the InnoForESt approach.

A governance innovation Navigator, as we understand it in InnoForESt, is strongly rooted in the socio-political context of the innovations that are studied and cannot instantly be separated from this context. To understand the variation across the innovation contexts, we have mapped the biophysical and institutional features of forest ecosystem service provision as well as studied the governance and stakeholder contexts of the innovations. All methods applied are tailored to the innovations to be analysed and further developed. In turn, this also means that a presentation of methods is not complete without outline of the innovations themselves. Hence, this Navigator also refers to empirical findings from the regional socio-political innovation contexts including the respective project’s practice and scientific partners, entities we term Innovation Regions. There are InnoForESt Innovation Regions, in which payment schemes for ecosystem services or variants thereof are introduced or developed further, for example, in Finland and Germany. Others rethink the way they convey knowledge about forest ecosystem services, as it happens in Sweden and Austria. In Italy, the provincial forest management agency undertakes efforts to innovate its management practices of their special land-use type, the mid-elevation forest-pasture landscape. Finally, in the Czech and Slovak Innovation Regions, new practices of collective forest management are explored.

After the introduction, in section 2, we present an overview of the theoretical background of the project (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 3.1, Sorge & Mann 2019) as well as the analytical approaches used to come to the empirical orientations based on Stakeholder Analysis (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 5.2, Schleyer et al. 2019), Governance Situation Assessment, and a reconstruction of the regional Innovation Journeys (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 4.3, Loft et al. 2019). Section 3 provides a deeper look at the methods used in InnoForESt, including a technology-assessment-based, multi-stakeholder-driven Constructive Innovation Assessment (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 4.2, Aukes et al. 2020a), experimental Role Board Games and the systematic development of prototypes (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 3.2, Kluvánková et al. 2019). In section 4, the Navigator ends with an outlook on plans how to convey the knowledge and methods acquired in the project in training circumstances, practice interactions, as well as the digital innovation platform which InnoForESt is developing.

This deliverable, elaborated under WP5 leadership, has been co-authored with colleagues from the entire project and is thus a true joint deliverable. It draws information from the other InnoForESt work packages by integrating their analytical approaches, tools, and methods employed. It reflects on possibilities and limitations, options and alternatives of the elements currently in use. It also builds on the experience of the six Innovation Regions identifying basic patterns of forest ecosystem services governance innovation in practice “that work”.

In the text, we refer to other results of the project that illustrate exciting aspects and from which further knowledge can be obtained: on the basis of which you can see how we did it in the project.

Non-technical summary

We aim for the Navigator to be a practical tool that should help finding orientation and direction for (forest) ecosystem innovation processes. To that end we provide suggestions for practical application throughout most of the sections.

This document outlines the approach the InnoForESt project has developed. It provides all project members and all others interested orientation about how InnoForESt worked. This is the reason why it is called a Navigator.

The report provides overview, examples, and guidance. It is less of a scientific character than a manual:

- In section 2, we present an overview of ways we do analysis and come to orientations about relevant processes influencing novel developments in the Innovation Regions.

- Section 3 provides a deeper look at the methods used in InnoForESt, including a method for “Constructive Innovation Assessment”, and experiments called “Role Board Games”. It also describes methods for developing test cases (“prototypes”) for the innovations, and for the reconstructions of the journey of an innovation (“Innovation Journeys”). The latter supports a better understanding of the innovation during the process and afterwards. A number of fact sheets about the methods employed are also available in this report.

- In section 4, we describe which training resources and interactions with practitioners were developed during InnoForESt. This section also includes a reflection on the digital innovation platform which InnoForESt has developed.

In the text, we refer to other results of the project that illustrate exciting aspects and from which further knowledge can be obtained: on the basis of which you can see how we did it in the project.

List of figures

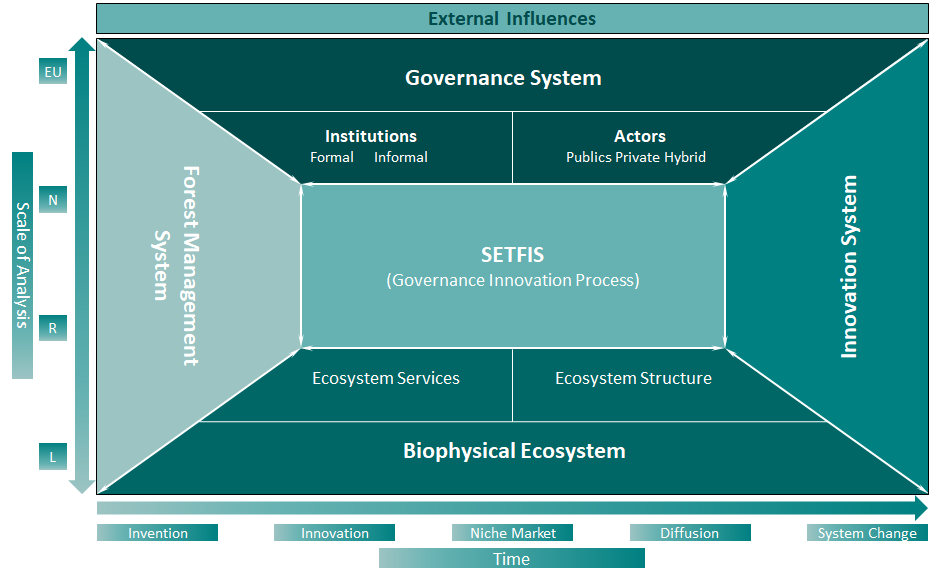

- Figure 2.1: Graphical representation of the Social-Ecological-Technical Forestry Innovation System framework

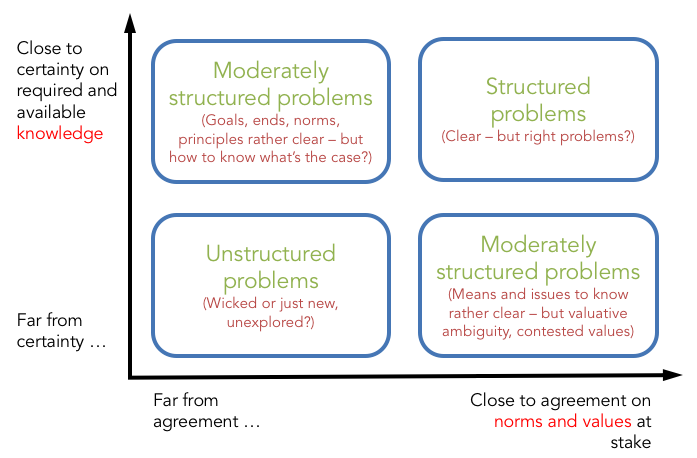

- Figure 2.2: The level of structuredness of problems on the axes of norms/values and knowledge

- Figure 2.3: Exemplary application of focus on structuredness of problems to forest ecosystem services issues

- Figure 2.4: Overview of the InnoForESt idealized innovation process

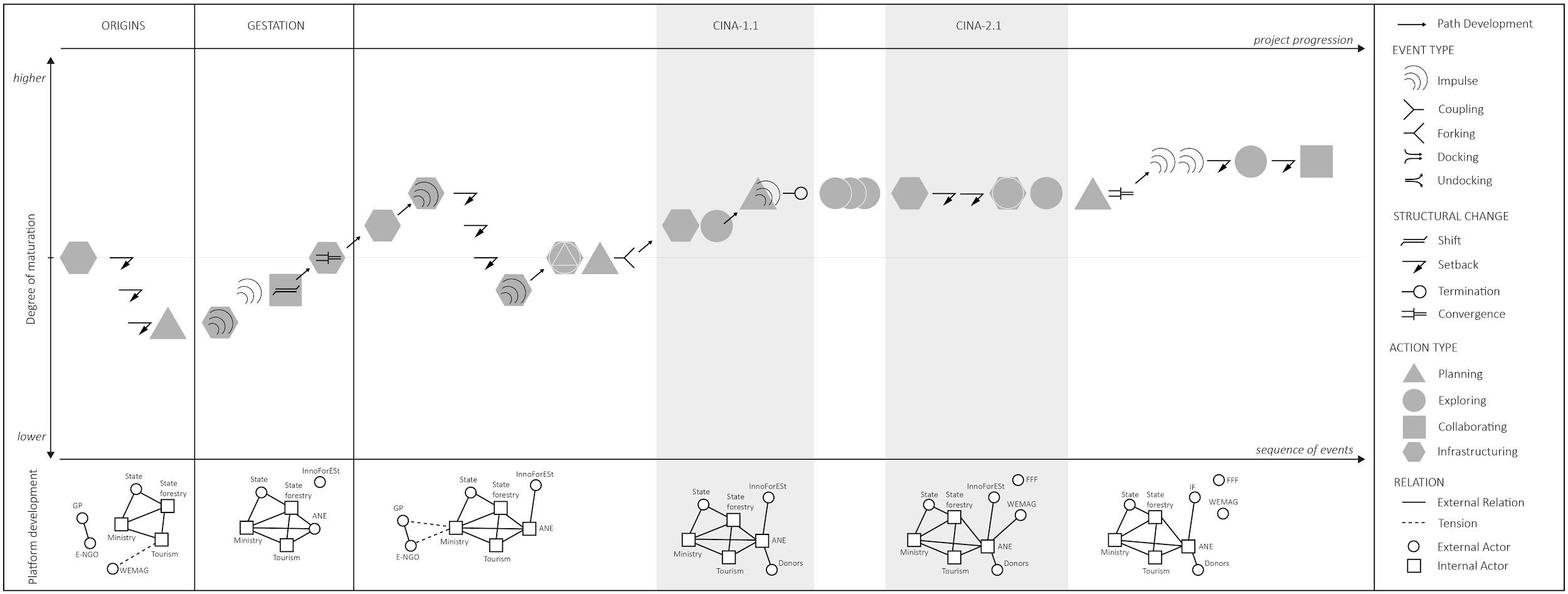

- Figure 2.5: Example of a visualization of a reconstructed Innovation Journey

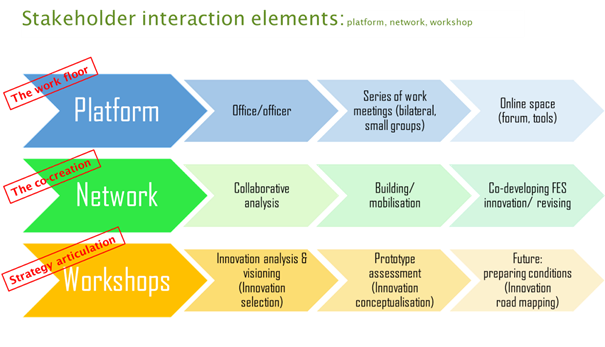

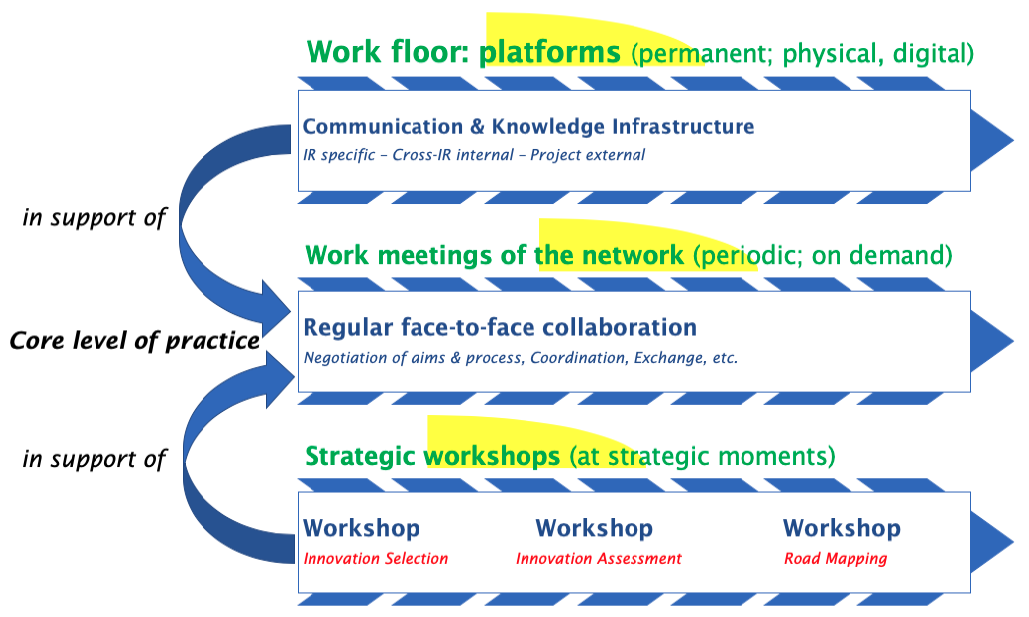

- Figure 3.1: The three types of processes in support of stakeholder interaction

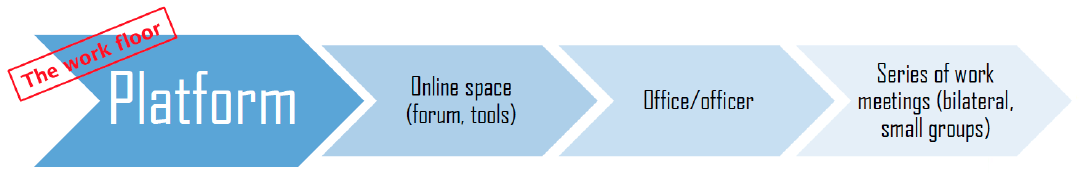

- Figure 3.2: The digital and physical meeting platforms

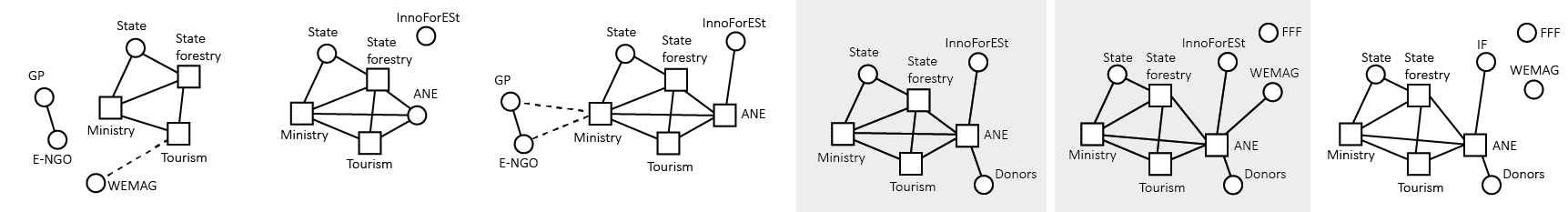

- Figure 3.3: InnoForESt Innovation Regions examples of stakeholder network development: a stable network in IR MVP

- Figure 3.4: InnoForESt Innovation Regions example of stakeholder network development: a dynamic network in IR Eisenwurzen

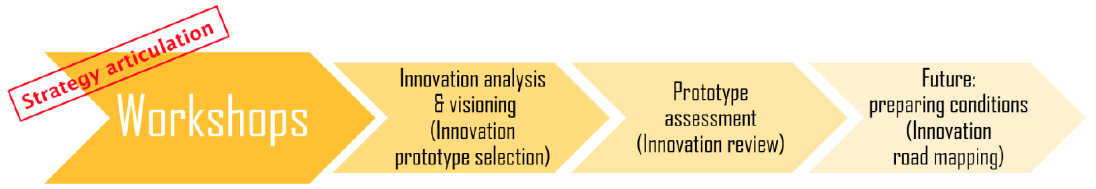

- Figure 3.5: Three directions of the strategy of the strategy articulation workshops

- Figure 3.6: Reconfigurations towards Innovation prototypes

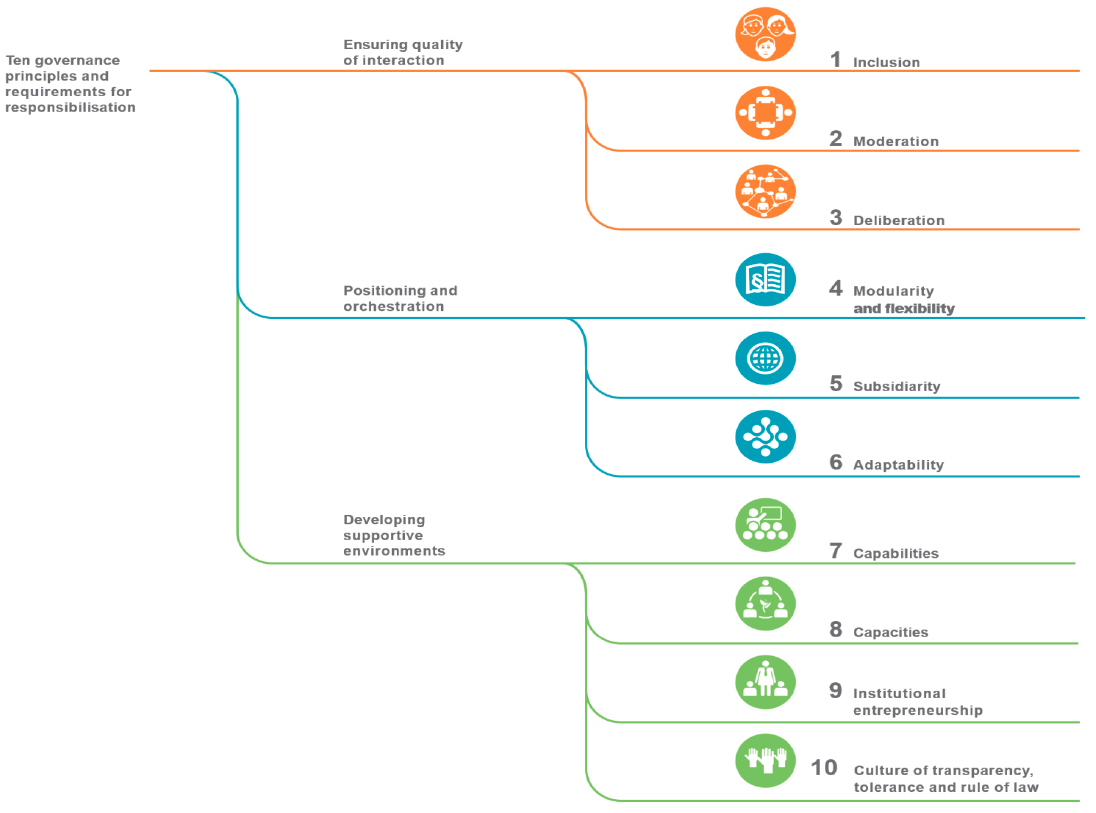

- Figure 3.7: Responsibility Navigator as developed in the FP7 Res-AgorA project

- Figure 4.1: Representation of scenarios as telescopes directed at the future

- Figure 4.2: Scenario combinations (colour groups) and their general thrust

- Figure 4.3: Principle coupling of CINA and innovation network processes

- Figure 4.4: Generic conceptualisations of a governance innovation situation

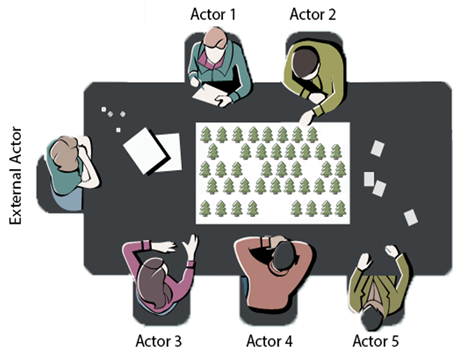

- Figure 4.5: Graphical illustration of InnoForESt Role Board Game

List of tables

- Table 1.1: Ecosystem services targeted in the Innovation Regions

- Table 2.1: Glossary of key terms and concepts used in this Navigator, and their definition characteristic for the InnoForESt project

- Table 2.2: Time scheduling help for the Stakeholder Analysis

- Table 2.3: Time scheduling help for Governance Situation Assessment

List of acronyms

| CINA | Constructive Innovation Assessment | LIB | Liberec region, Czech Republic |

| CICES | The Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services | MAES | Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services |

| CLC | CORINE Land Cover | MLP | Multi-Level Perspective |

| CORINE | Coordination of Information on the Environment | NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| CTA | Constructive Technology Assessment | Oppla | Operationalisation of Natural Capital and Ecosystem Services |

| Dx.y | Deliverable x.y | PAT | Provincia Autonoma di Trentino (Autonomous Province of Trentino), Italy |

| EU | European Union | PES | Payments for Ecosystem Services |

| EW | Eisenwurzen region, Austria | RBG | Role Board Game |

| FES | Forest Ecosystem Services | STA | Stakeholder Analysis |

| FIN | Finland | SETFIS | Socio-ecological Technical Forestry Innovation Systems |

| GSA | Governance Situation Assessment | SME | Small and Medium-sized Enterprises |

| HYB | Hybe (region in Slovak Republic) | WP | Work package |

| InnoForESt | Smart information, governance and business innovations for sustainable supply and payment mechanisms for forest ecosystem services |

Deliverables

| D2.1 – Deliverable 2.1: | Mapping of forest ecosystem services and institutional frameworks, draft report |

| D3.1 – Deliverable 3.1: | Analysis framework for governance of innovation factors in business and policy processes for forest ecosystem services |

| D3.2 – Deliverable 3.2: | Application Summary of Prototypes for Ecosystem Service Governance Modes – Demonstrator |

| D4.1 – Deliverable 4.1: | Mixed method matching analysis: Suggested methods to support the development and matching of prototypes to the different Innovation Regions |

| D4.2 – Deliverable 4.2: | Set of reports on CTA workshop findings in case study regions, compiled for ongoing co-design and knowledge exchange |

| D4.3 – Deliverable 4.3: | The emergence of governance innovations for the sustainable provision of European forest ecosystem services: A comparison of six innovation journeys |

| D5.2 – Deliverable 5.2: | Report on stakeholders’ interests, visions, and concerns |

| D5.3 – Deliverable 5.3: | Final report on CINA workshops for ecosystem service governance innovations: Lessons learned |

| D5.4 – Deliverable 5.4: | Design on training events to develop innovation |

| D6.3 – Deliverable 6.3: | Set of policy recommendations for EU wide governance strategy for sustainable forest ecosystem service provisioning and financing |

Work packages

WP1 – Project management and coordination

WP2 – Mapping and assessing forest ecosystem services and institutional frameworks

WP3 – Smart ecosystem services governance innovations

WP4 – Innovation platforms for policy and business

WP5 – Innovation process integration

WP6 – Policy and business recommendations and dissemination

WP7 – Ethics requirements

1 Introduction

This InnoForESt Navigator provides an integrated view on the core approach chosen by the project partners. Its main aim is to observe existing innovations and stimulate new and further innovations of forest ecosystem services governance. We take stock of what has been developed in the InnoForESt project. It collects, interprets and explains, as well as translates useful strategies for forest ecosystem services governance innovations into practical terms. We aim for the Navigator to be a practical tool that should help finding orientation and direction for (forest) ecosystem innovation processes. To that end we provide suggestions for practical application throughout most of the sections.

As a project, InnoForESt was constructed to assist innovations in six different practice contexts. We called these practice contexts ‘Innovation Regions’. This comprised all of the practices, stakeholders, policies, and places that encompass the targeted innovation. The six Innovation Regions revolved around the following innovations:

- Eisenwurzen, Austria (EW): exploration of ways to strengthen existing and constructing novel value chains around forest products, potentially including material products (e.g., furniture, tiny houses) as well as educational programmes and tourism activities

- Southern Finland, Finland (FIN): operationalisation of a ‘payments for ecosystem services’ scheme in the form of a habitat bank acting as intermediary for (corporate) investments in forest biodiversity protection

- Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany (MWP): expanding an existing payment for ecosystem services scheme involving tree planting by investors

- Fiera di Primiero, Trentino, Italy (PAT): exploration of new ways to maintain and sustain existing management practices for a specific landscape type: mid-elevation forest-pastures

- Gothenburg, Sweden (GOT): Redevelopment of a multi-stakeholder program for increasing childrens’ and young adults’ knowledge about forests and their ecosystem services in times of climate change

- Liberec, Czech Republic/Hybe, Slovak Republic (LIB/HYB): exploration of new ways to manage forests in a collectively-owned, self-organised forest socio-ecological systems.

The innovations pursued in the Innovation Regions selected by the project involved a variety of forest ecosystem services. This gave us a comprehensive overview of practices ‘that work’ in terms of making our societies’ relation to forests more sustainable. Table 1.1 shows which services in the broader sense were targeted in which Innovation Region.

The Navigator shows how the individual analytical approaches, tools, and methods applied in the project fit together despite their diversity. It reflects on possibilities and limitations, options and alternatives of the elements. Thus, drawing on the experiences of the six Innovation Regions, this report helps to identify and clarify basic patterns of forest ecosystem services innovation practice ‘that work’.

| Ecosystem service | EW | FIN | MWP | PAT | GOT | LIB/HYB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timber | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | -/✓ | ||

| Non-timber products | ✓ | |||||

| CO2 sequestration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓/✓ | |||

| Water regulation | ✓ | |||||

| Biodiversity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓/✓ | |||

| Natural hazards protection | ✓ | |||||

| Tourism and recreation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓/✓ | ||

| Spiritual values | ✓ |

2 Set of utensils

In this section, we present and briefly explain the heuristics that helped the project to explore and assess the six Innovation Regions. This includes a glossary of core terms; the mapping of associated political and biophysical circumstances for forest ecosystem services governance innovations in the seven countries where the innovations took place; a conceptual framework developed by InnoForESt to analyse influential factors in socio-ecological technical forestry innovation systems (SETFIS; cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 3.1, Sorge & Mann 2019); suggestions for how to study the involved actors and governance situation (cf. InnoForESt Deliverables 5.2, Schleyer et al. 2019, and 5.1, Aukes et al. 2019); a description of how InnoForESt envisioned the ideal innovation process; and an analytical method helping to understand and learn from the course, i.e., ‘journey’, of an innovation retrospectively.

These utensils are used side by side. They complement each other: the glossary defines the key terms so that one has a common language regulation in the project, SETFIS offers the conceptual framework so that one shares coherent basic assumptions in the project, the mapping provides an overview of the other forest ecosystem services landscape, the Stakeholder Analysis and the Governance Situation Analysis translate all of this into specific questions for the site in the regions in which the innovations are to take place before the innovation work begins, and the other tools help to bring all of this into a concerted process and allow for systematic reflection on what is actually happening.

Each topic in this section follows a similar structure. First, it describes what the item or method is meant to be. Second, it describes how one may use it. Third, the limitations of the item or method in question are listed. Finally, the item or method is presented as it was applied or used over the course of InnoForESt.

We would like to point out that the texts that follow in sections 2.4 and 2.5 had the character of manuals or handouts in the project context.

2.1 Utensil 1: Glossary of core terms and heuristics

What is this?

- Large international projects encompassing multi-actor approaches, like InnoForESt, require a shared terminology in order to develop a common conceptual understanding.

- This glossary is an alphabetical compendium of key terms with common usage in the project. It served as a pivotal element for coherent communication and to be able to link findings within the project.

- Several of the key terms in Table 2.1 originated in the InnoForESt proposal. These were continuously complemented based on discussions during periodic project meetings. The compilation of the glossary was an ongoing activity of improving and reviewing shared terminology throughout the course of the project.

- The common terminology of notions summarized in the glossary served as a point of reference – as an integration device on project level.

How to use it?

- The concepts presented below offered the chance to get a better idea of what we meant with certain terms in this project as a whole, as compared to specific literature or individual use.

- The glossary was used as a reference to enable clarifications during project meetings or workshops with different stakeholders.

Limitations of use

- We are aware that other – in some cases also scientific – meanings of some terms exist, and we do not claim exclusiveness.

- Indeed, the glossary was neither supposed to replace the local language, which may have relevance for the actors in the Innovation Regions, nor to render readers’ translation of the notions into the local mindsets and practice contexts unnecessary.

| Key term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Biophysical and Institutional Mapping | Europe’s biophysical forest ecosystem services are well understood on a general level. InnoForESt refines the knowledge base by providing fine-grained maps of the supply of selected, relevant forest ecosystem services in Europe. The institutional mapping component adds knowledge about future societal demand for forest ecosystem services based on public policy. These mapping processes are not a stand-alone effort. They also provide relevant background knowledge for the Innovation Teams to understand and manage their innovation in their specific local context (WP4 and WP5). |

| Business model | “Representation of a firm’s underlying core logic and strategic choices for creating and capturing value within a value network” (Shafer, Smith, & Linder 2005: 202) Key components: the sample of strategic choices, the creation of value, the network, and the value preservation |

| Constructive Innovation Assessment (CINA) | Constructive Innovation Assessment (CINA) is the method for innovation assessment in InnoForESt, inspired by Constructive Technology Assessment (Schot & Rip 1997). It consists of a series of workshop activities, including preparation and evaluation, reflection, and learning materials, for multi-stakeholder constructive visioning and assessment of the six governance Innovation Regions in focus. |

| Digital innovation platform | Digital innovation platforms are virtual spaces for knowledge exchange. As part of the InnoForESt webpage (www.innoforest.eu), each Innovation Region will be provided with a space, which has an open public part presenting the innovation in the respective local language and in English; and a protected space which the Innovation Teams can use for sharing information with their local network. The digital platform, like a physical one, should serve the stakeholders communication and exchange, and are co-designed with Innovation Teams. |

| Ecosystem service governance innovations | The six initial governance innovations in InnoForESt are different Payment schemes for forest Ecosystem Services (PES) and new partnerships, network approaches, or actor alliances. Payment schemes are in focus in Germany, Slovakia, Finland, and Italy; network or partnership approaches characterise the innovations in Austria, Czech Republic (as well as PES), and Sweden. |

| Ecosystem service governance Navigator | The Ecosystem service governance Navigator has the function for the project to provide an integrated view on the core approach chosen to stimulate and observe innovations of forest ecosystem governance. In this interim’s version, we take stock of what has been developed during the first year of the project. It collects, interprets and explains, as well as translates useful strategies for forest ecosystem services governance innovations into more practical terms. |

| Fact sheet | These overviews provide easily accessible information about the diverse set of methods used in InnoForESt. By detailing the processes and suitability of the methods in different phases of an innovation process, the fact sheets present innovators in other innovation contexts with a toolbox to enrich the understanding of their Innovation Region and help them push their innovation. |

| Factor reconfiguration | Factor reconfiguration means hypothetical or real experimenting with changes in (key) factors when seeking a different design that can potentially work on a larger scale or in a different context. |

| Factors | Factors are “observed conditions or processes that influence the innovation and its development process.” (InnoForESt Deliverable 3.1, Sorge & Mann 2019: 3) |

| FES | Forest Ecosystem Services |

| Forest Ecosystem Service categories | 1. Provisioning: Includes all material outputs from forest ecosystems, such as wood, mushrooms, berries or game. These are tangible things that can be exchanged or traded, as well as consumed or used directly or processed, e.g., for construction, energy or food.

2. Regulating: Includes all the ways in which ecosystems regulate ecosystem characteristics, functions or processes, such as drought resistance, carbon sequestration or water cycles. People benefit from these services directly and indirectly. 3. Cultural: Includes all non-material ecosystem outputs that have symbolic, cultural or intellectual meaning or value (including, e.g., recreation). |

| Governance Situation Assessment | The Governance Situation Assessment in InnoForESt serves two purposes. Knowing about governance arrangements, histories, structures and processes not only provides an overview of the socio-political context in which an innovation is taking place or is planned, but also lays the groundwork for the development of scenarios that can be used in strategic workshops for the purpose of Constructive Innovation Assessment. |

| Idealised innovation process | The idealised innovation process depicts what should happen in Innovation Regions in order to best analyse, develop, and foster governance innovations for forest ecosystem service provision. The process consists of three interlinked elements: innovation platforms, networking activities, and workshops. |

| Innovation Journey | Innovations are conceived as a process or a journey and not solely as a product. The Innovation Journeys are reconstructions of innovation processes as an opportunity to get an overview of the mechanisms and dynamics of the innovation processes themselves. |

| Innovation Partner (IP) | Refers to the practice partners in Innovation Regions. |

| Innovation Region (IR) | Refers to the six initial governance Innovation Regions in InnoForESt (formerly ‘Case Study Regions’). |

| Innovation Team (IT) | Innovation Teams (ITs; formerly ‘Case Study Teams’) consist of the science partner and the practice partner who are cooperating in the Innovation Regions. |

| Matching framework | The matching framework offers methods to assist in innovation and prototype development and assessment, which includes the assessment of their transferability to other places (matching). |

| Matching tool | The matching tool helps to identify contexts in which certain prototypes have potential to be fed into another context. The methods used for matching could be something very simple like an Excel table or much more complex (e.g., Stakeholder Analysis, Governance Situation Assessment, Net-map, etc.).

The idea – in this project – is to develop a European matching tool to identify places with potential for innovations, e.g., as web-based devise, potentially to be integrated into the Oppla website . |

| Partners: Practice partners Science partners | Together, as multi-actor teams, practice and science partners facilitate the innovation processes in the six Innovation Regions, starting as regional innovation network approaches that become scaled up (and interconnected) to national and to EU-wide networks on good innovation practices for exchange and learning.

Practice partners provide or establish the innovation network and stimulate the forest ecosystem services governance innovation idea. All scientific work and effort is supposed to contribute to the practice partners’ objectives. Practice partners include public policy agencies, private forest owners and enterprises, industry partners, environmental NGOs, as well as tourism and hunting associations. Science partners are research institutes from – or linked to – the six Innovation Regions collaborating with the practice partners to analyse and support the innovations scientifically. |

| Prototype | A prototype refers to a vision (a scenario, scenario narrative, and model) that describes the future development of governance innovation in focus. Future development directions are agreed upon by the Innovation Teams and stakeholders of governance innovation in terms of its upgrading and upscaling potentials. A prototype is based on the reconfiguration of factors (factors analyses) that improve the initial innovation. Prototypes of innovations are different from the initial innovation as they are a future vision that allows for an abstraction of conditions (i.e., decontextualized from the initial innovation context). |

| Role Board Games (RBG) | A Role Board Game is used for testing the innovation factors as well as testing and making visible behavioural changes of stakeholders in different settings. It also facilitates the stakeholders (or partners) to learn from each other during the game and to develop a mutual understanding. This is expected to foster innovations and problem solution strategies and sustainability-oriented behaviour, from individual towards collective level which, ideally, enables more sustainable behaviour of all stakeholders involved. |

| Scenario | A scenario, as InnoForESt understands it, is at the same time a ‘useful fiction’ and a ‘holding device’. A ‘useful fiction’ is a coherent story or plot of a world, in which the innovation has taken on a specific shape. A ‘holding device’ is a condensation of what is known about one specific possible development. In other words, a scenario is a thoughtful, systematic, rich mixture of creativity based on prior knowledge of the governance situation. See section 5.1 for more detail. |

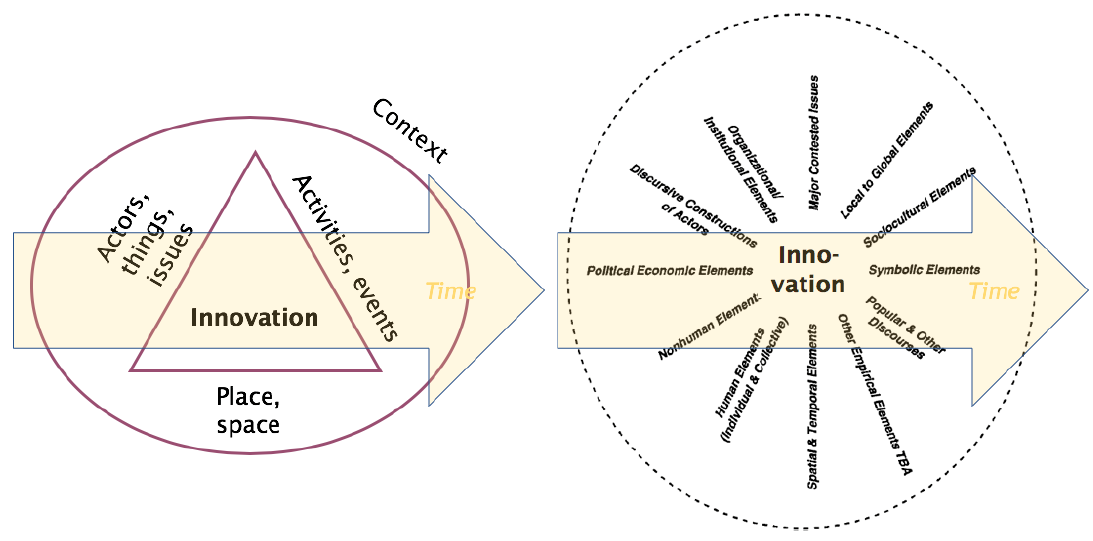

| Socio-ecological technical forestry innovation systems (SETFIS) | This is the analysis framework for the governance of policy and business innovation types and conditions. It serves as an analytical lens to support the exploration of influencing factors on governance innovations to secure a sustainable provision of forest ecosystem services. The creation of the analysis framework builds on the idea of complex processes within linked social-ecological-technical-forestry-innovation systems (SETFIS) of the InnoForESt Innovation Regions. |

| Stakeholder Analysis | InnoForESt has carried out a stakeholder analysis in each Innovation Region. Such a mapping exercise is meant to find out about a broad range of stakeholder categories. It is necessary to cover such a broad, exploratory range of stakeholders as characteristics that are (potentially) important when shaping or fostering the governance innovation processes will differ across innovation contexts. |

| Strategic workshop | Constructive Innovation Assessment (see elsewhere in this glossary) is carried out in strategic workshops. As opposed to regular work floor interactions, these strategic workshops are characterised by a careful preparation including the (further) development of scenarios representing possible innovation prototypes. |

| Support products | InnoForESt produces a range of tailor-made support products that assist workshop activities and networks. These products are available at different points in time and relate to different innovation activities. Science partners in Innovation Teams function as translators for scientific support requests. Products are listed in the Appendix presenting “The idealised innovation process” and will be available on the digital innovation platform. |

| Training | InnoForESt’s approach will be translated into a training manual for practitioners. The training materials are based on internal training sessions as well as other products and deliverables of the project. This contributes to InnoForESt’s sustainability and enables the transfer of the approach to other innovation contexts. |

| Typology of Forest Ecosystem Services Governance Innovation Situation | The assessment of the governance situations in the Innovation Regions delivered a preliminary typology of governance innovation situations (see elsewhere in this glossary). Eleven categories were distinguished to meaningfully compare governance situations across such different innovation contexts. Based on the innovation analytical approach taken in InnoForESt, these categories cover different levels of the socio-technical system that is the innovation, e.g. regime, niche, and landscape developments. In addition, it maps the core issues in the innovation context and assesses their structuredness (see Fact sheet on Governance Situation Assessment for more details). |

| Typology of Forest Ecosystem Services stakeholders | Based on a thorough stakeholder analysis in InnoForESt’s Innovation Regions, patterns of stakeholders were distinguished. The typology differentiates between stakeholders’ (a) sphere, (b) business type, (c) scale, and a qualitative assessment of their (d) openness to innovation. |

| Work floors / work meetings | As opposed to strategic workshops, work floors or work meetings are all interactions between the Innovation Team and stakeholders that are not linked immediately to the discussion of scenarios. Think of simple phone calls to catch up with certain stakeholders, discussions in preparation of workshops or bringing stakeholders in contact with each other. |

2.2 Utensil 2: Biophysical and institutional mapping

What is this?

As both ecological and institutional contexts matter for innovations in the forest sector, InnoForESt provides a first basis for a context-relevant analysis of innovation evolution, which supports both evaluating where innovations originate, and learning from innovations elsewhere. In general, there is a good spatial understanding of Europe’s biophysical forest ecosystem services (Maes et al. 2013), but ecosystem service supply and demand have been matched only as rough estimates of scarcity (Burkhard et al. 2012). InnoForESt has complemented this understanding by elaborating forest ecosystem service provision through an analysis of biophysical bundles and clusters in the European landscape (Orsi et al., 2020), through an institutional analysis of forest ecosystem service demand, innovations and governance (Primmer et al., 2021), and rights and responsibilities (InnoForEst Deliverable 2.2, Varumo et al. 2019).

InnoForESt Deliverable D2.1 (Primmer et al. 2019) proposes that societal demand can be derived from formal goals and argumentation in public strategies and laws, as these are the results of processes engaging societal actors and experts. In the past years, several European policies have gradually taken up the notion of ecosystem services, and the European Forest Strategy fares well in reference to and integration of the term (Bouwma et al. 2018). To complement this understanding, InnoForESt analyses the ways in which national forest related policies recognise forest ecosystem services and how this recognition coincides with biophysical ecosystem service supply at the spatial scale.

The biophysical mapping of forest ecosystem services focuses on the supply of ecosystem services, identifies the relevant services and defines indicators to map the selected ones. Pan-European maps are produced using the ‘Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services’ (CICES) as well as the ‘Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services’ (MAES) indicators using ‘Coordination of Information on the Environment Land Cover’ (CORINE or CLC) and MAES data and published literature, as reported in InnoForESt Deliverable D2.1 (Primmer et al. 2019). The relevant forest ecosystem services are:

- Presence of plants, mushrooms and game

- Biomass

- Bioenergy

- Mass stabilization and control of erosion rates

- Water retention potential

- Pollination potential

- Habitat maintenance and/or protection

- Soil organic matter

- Carbon storage

- Experiential and recreational use

- Symbolic value.

The institutional mapping is designed to identify future societal demand for forest ecosystem services, as formalized and expressed in policy, i.e., policy demand. The policy demand is analysed through detailed policy document analysis, for which a protocol and database are developed and reported in InnoForESt Deliverable 2.1 (Primmer et al. 2019). The mapping focuses on forest strategies in the Innovation Regions and their countries as well as in other forested countries of Europe. Also, biodiversity strategies and bioeconomy strategies are analysed in the Innovation Regions or their countries.

Based on the combination of biophysical and institutional mapping, InnoForESt recognizes the connection between abundance or scarcity of forest ecosystem services and their coincidence with strategic commitment to innovations and new governance mechanisms. The mapping supports the transfer of innovation as well as upscaling and further co-learning in comparative high potential context regions.

How to use it?

- InnoForESt innovations can be included in the output map as pins with pop-up boxes of information.

- Innovation Teams and Innovation Regions in InnoForESt and beyond can look for similar forest ecosystem services and/or institutional conditions for transferring their ideas.

- Innovation promoters, such as policy-makers can look for biophysical and institutionally favourable innovation and governance settings for the promotion of sustainable use and provision of ecosystem services.

Limitations for use

- The six InnoForESt innovations provided much detailed understanding of innovation processes, but this kind of rich data cannot be mapped.

- The mapping is coordinated with InnoForESt’s sister project SINCERE , to include over a hundred innovations as pins onto the map. If this does not eventuate, the map will include relatively little about innovations.

2.3 Utensil 3: Social-Ecological-Technical Forestry Innovation Systems (SETFIS)

What is this?

For a better understanding of governance innovations for forest ecosystem service provision, InnoForESt developed an analysis framework (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 3.1, Sorge & Mann 2018).

The framework helps stakeholders to gain a good understanding of what influenced innovation development in terms of fostering or hindering context conditions. It explains the emergence, growth, and spread of successful governance innovations for the sustainable provision of forest ecosystem services taking ecological, social, institutional and technical context conditions into account.

Assuming that all types of innovations emerge in interconnected social-ecological-technical forestry systems, the analysis framework serves as an analytical lens to explore key factors that are influencing governance innovation types, processes and outcomes. Insights from such SETFIS analysis support local decision makers from forest science, policy and practice in two ways:

a) Retrospectively, to gain a good understanding of the emergence and development of forest governance innovations (i.e., what factors have influenced the innovation, from early ideas of its emergence and its developments until now); and

b) Prospectively, on crucial conditions enabling their upscaling and upgrading potentials (i.e., what is needed for a similar innovation elsewhere, or an improved version of the innovation in the current context; how to reduce risks for failure).

However, systematic connections between social, biophysical, and technological context conditions on innovation development are scarce. Consequently, InnoForESt’s SETFIS (Social-Ecological-Technical Forestry Innovation System) analysis framework builds on and combines theories and concepts in the realm of social-ecological systems (e.g., McGinnis & Ostrom 2014; Ostrom 2011), institutional economics (e.g., Hagedorn 2008; North 1990), environmental and transformation governance (e.g., Armitage et al. 2009; Gunderson 2002; Jordan 2001; Kemp et al. 2007; Olsson et al. 2004), and socio-technical and innovation systems (Asheim et al. 2011; Geels & Schot 2007; Voß & Fischer 2006) to describe the complexity of governance innovation development. As an inherent part of SETFIS, ideas of multiple-administrative levels and sectors, multiple actors, and multiple rationalities (Loft et al. 2015) are integrated in the design of the analysis framework.

However, systematic connections between social, biophysical, and technological context conditions on innovation development are scarce. Consequently, InnoForESt’s SETFIS (Social-Ecological-Technical Forestry Innovation System) analysis framework builds on and combines theories and concepts in the realm of social-ecological systems (e.g., McGinnis & Ostrom 2014; Ostrom 2011), institutional economics (e.g., Hagedorn 2008; North 1990), environmental and transformation governance (e.g., Armitage et al. 2009; Gunderson 2002; Jordan 2001; Kemp et al. 2007; Olsson et al. 2004), and socio-technical and innovation systems (Asheim et al. 2011; Geels & Schot 2007; Voß & Fischer 2006) to describe the complexity of governance innovation development. As an inherent part of SETFIS, ideas of multiple-administrative levels and sectors, multiple actors, and multiple rationalities (Loft et al. 2015) are integrated in the design of the analysis framework.

To allow and navigate users through such kind of analysis, we translate the system dimensions and the related influencing factors into qualitative questions to identify and explain how innovations emerge, develop, and unfold. This creation of knowledge with help of focused interviews with stakeholders closely involved in innovation activities helps to explicate the connection and interrelation between social-ecological-technical influences on governance innovations in a holistic and comparative way in Europe. As such, SETFIS analysis allows to detect key factors that influence governance innovation development in particular situations such as in our Innovation Regions, but also identifies similarities and differences across Innovation Regions. Over the time of SETFIS application, insights are gained on factors that play a general crucial role for innovation development where decision-makers can concentrate/focus on.

InnoForESt project partners have empirically applied the SETFIS analysis framework in the six Innovation Regions. In qualitative interviews and/or as part of strategic CINA workshops, stakeholders reveal the development history of ‘their’ governance innovation and are guided through the exploration of the forestry innovation system (InnoForESt Deliverable 4.2, Aukes et al. 2020a). In this process, both scientific partners and practice partners gain a good understanding of past and present innovation dynamics, which enables them to purposefully create an innovation-friendly environment, such as the adaptation of key influencing factors that are favouring certain intended development paths (see also InnoForESt Deliverable 5.3, Aukes et al. 2020b).

The analysis reveals critical forestry innovation system conditions and factor interdependencies together with stakeholders. These insights can be integrated into road mapping strategies for improving governance innovations in the light of the vision and ideas of participating actors. As such, the SETFIS analysis framework supports collecting information in a comparable way across Innovation Regions by analysing, diagnosing, explaining, and predicting system dimensions, influencing factors, outcomes, and requirements for governance innovations to emerge, develop, and work in an intended way. In combination with the CINA workshops (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 4.2, Aukes et al. 2020a) and the Role Board Games (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 3.2, Kluvánková 2020), these insights are one important basis for respective policy and business recommendations that create enabling conditions for the sustainable provision of forest ecosystem services (InnoForESt Deliverables 3.2, Kluvánková et al. 2020, and 5.3, Aukes et al. 2020b).

Forest and forestry-related decision-makers gain a better understanding of conditions and contexts that encourage and foster governance innovations and their uptake in the forestry sector. The implications for forest owners, and other local stakeholders, are to diversify their product and service portfolios. Ideally, service providers in the Innovation Regions benefit from creating favorable innovation conditions that allow new business opportunities, the creation of new income streams and job possibilities. Ideally, this leads to an increased provision in particular of regulating and cultural forest ecosystem services, such as carbon storage, improvement of biodiversity habitat, and recreational opportunities, etc.

How to use it?

- Application of the framework: The analysis framework serves as a checklist for comprehensively analysing the context conditions (organised as system dimension and potentially influencing factors) that have influenced governance innovation development in a region. The framework also offers a set of questions (Appendix of framework document, cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 3.1, Sorge & Mann 2019) asking for current information on biophysical, social, institutional and technical conditions in order to organise and generate insights into historical developments, and assumptions of future developments of the innovation in focus.

- Data generation and analysis: Information about innovation development is generated with help of semi-structured interviews, focus groups or workshops with key stakeholders in Innovation Regions. The set of questions helps to categorise and evaluate the influence of framework dimensions and factors that might have played out in particular contexts.

- Translating results into future steps & strategies: Results are translated into future steps for action (Road map) for concerned stakeholders in Innovation Regions. Based on insights on crucial influencing factors that are fostering certain innovation developments as well as the challenges and threats for innovations, strategies can be jointly developed to create favourable conditions in a structured and targeted way.

Limitations for use

- SETFIS provides an orientation, not a prescription: The set of questions is meant as an orientation to elaborate on factors influencing innovation. It is designed to detect further influences which are deemed important by stakeholders. We inserted open questions to improve our understanding of governance innovations design and functioning, and also to constantly constantly improve the conceptual understanding of innovation development by each application. Also, not every question has to be asked, in particular when information has been already gathered by other project activities.

- Dimensions, no sequence: The sequence of analysis questions does not need to follow the sequence of dimensions as presented in this guideline; interviewees are free to reshuffle, combine questions or change them to ‘yes-no’ answers to ease the evaluation. However, for reasons of comparability among the different Innovation Regions, all dimensions should be covered in innovation assessment.

2.4 Utensil 4: Stakeholder Analysis

What is this?

This tool describes the analytical framework and provides practical guidance for identifying (potentially) relevant stakeholders in an Innovation Region and for assessing their characteristics including their interests, visions, and concerns as well as interlinkages between them (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 5.2, Schleyer et al. 2019; see Appendix I). While the main focus lies on stakeholders at the local and regional level, the tool can also be used to identify and assess relevant national, European or even ‘global’ stakeholders. The generic Stakeholder Analysis carried out here is one cornerstone of the subsequent Governance Situation Assessment (cf. section 2.5 below); it allows for comparative analyses of relevant characteristics and stakeholder types across Innovation Regions, and contributes to the development of a corresponding Stakeholder Analysis cutting across the entire project.

How to use it?

- In practice, this tool suggests, first, a broad and rather comprehensive list of stakeholders and stakeholder types potentially relevant for fostering or hampering the governance innovation (process) in an Innovation Region. This does not mean that all stakeholder types are likely to be relevant in each and every Innovation Region and thus would need to be analysed in depth. Rather, it can be seen as some kind of ‘checklist’ Innovation Teams can use to decide which stakeholder (groups) might be relevant and thus would need to be considered in the Stakeholder Analysis in their Innovation Region. At the same time, this list can be complemented by stakeholders not yet featured in the list, but with high relevance for the respective governance innovation.

- Second, the tool provides an extensive overview of analytic categories to be covered by the empirical analysis, i.e. the potentially relevant stakeholder characteristics. Again, this is meant to be an initial starting point for, for example, designing semi-structured interview guidelines. It can – and should – be complemented with questions about additional characteristics considered particularly relevant for the governance innovation (process) under scrutiny.

- Third, a diverse set of empirical approaches is suggested, from which Innovation Teams can choose when planning the Stakeholder Analysis. Which approach to choose certainly depends, among others, on the already existing knowledge of stakeholder constellations and stakeholder interests and characteristics, the resources available to carry out such a Stakeholder Analysis, and the number and types of stakeholders to be covered.

- Forth, the visualization of stakeholder mappings (e.g., in Venn diagrams) as well as the presentation as posters at physical meetings of the Innovation Teams may facilitate the comparison of and reflection on the different stakeholder networks in the Innovation Regions and thus stimulate discussions between the Innovation Teams.

Limitations for use

- Although the tool neither prescribes a concrete number of stakeholders to be analysed, nor the level of detail on which to explore stakeholder characteristics, nor the empirical approach for collecting the stakeholder-relevant information, the sheer range of potential stakeholders and their characteristics potentially worthwhile to investigate may be perceived as overwhelming by the Innovation Teams.

- Time and other resources may be critical and/or limited on part of the Innovation Teams, or the team members tasked to carry out the Stakeholder Analysis. First-hand experiences with some of the empirical methods suggested may be limited. Here, a careful, yet thorough assessment of the knowledge gaps with respect to stakeholders and their characteristics and their relevance for the governance innovation under scrutiny is needed to enable the Innovation Team to choose the appropriate range and level of their empirical approach.

- Synergies with the concrete way of carrying out the Governance Situation Assessment that builds upon the Stakeholder Analysis will need to be explored.

- Even a carefully and properly conducted Stakeholder Analysis will only be able to capture the status quo. With the governance innovation (process) progressing, stakeholder constellations may change, as may the vested, specific interests of stakeholders involved in the governance innovation (process). Thus, procedures would need to be defined for updating and/or expanding the Stakeholder Analysis to account for the changes in context or focus of the respective governance innovation (process).

2.4.1 Main purpose of Stakeholder Analysis

The project aims for an integrated approach to knowledge generation, stakeholder interaction, and triggering governance innovation. For such a purpose, it is crucial to identify and map a diversity of stakeholder characteristics, including their interests, visions, and concerns (e.g., civil society perceptions, user demands, facilitators’ suggestions etc.) both regarding forest ecosystem services and in general. The Stakeholder Analysis is not carried out by an external party, but by the local innovators, i.e., the Innovation Teams, themselves, as they already have a feeling for potential conflicts and sensitivities in the area. Findings from the Stakeholder Analysis can feed into a typology for understanding the bigger picture and comparing the Innovation Regions and the respective governance innovations (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 5.2, Schleyer et al. 2018). As a second aim, a deeper understanding of the stakeholder constellations in an Innovation Region enables a confident and cognisant facilitation of the co-production process of the innovation.

2.4.2 Typology and analysis of Forest Ecosystem Services stakeholders

In practice, Innovation Teams are chiefly responsible for the empirical work. To allow for the comparison of stakeholder constellations across Innovation Regions, the categories of the stakeholder analysis have to be harmonised somewhat (i.e. targeted stakeholder types, analytical categories for stakeholder characteristics, and appropriate empirical methods). While harmonisation for the purpose of comparison is necessary, one needs to make sure that the special characteristics and peculiarities of the Innovation Regions are still visible and reflected in the findings. This will lead to the development of a cross-cutting stakeholder typology.

Note that the results of the individual Stakeholder Analyses are crucial ingredients for the innovation processes: Innovation Teams need them to plan the innovation co-production activities.

The Innovation Teams probably have some level of knowledge about the relevant stakeholders already. Whatever actual or perceived knowledge gaps exist on part of the Innovation Teams influences the data gathering method as well as the categories used to analyse those data. In addition, which stakeholders to interview or to enquire about as part of the Stakeholder Analysis depends on the required knowledge and expertise.

The following contains a suggested list (a) stakeholder types to be considered; (b) analytic categories of stakeholder characteristics; and (c) a range of possible empirical tools and methods to be employed:

- Stakeholder types that might be considered in the Stakeholder Analysis include (not restricted to; might be partly overlapping):

- Forest owners (public, private, collective)

- Land owners (outside forests) (public, private, collective)

- Forest managers/farm managers (might overlap with owners, but not necessarily so)

- Protected Areas organisations (National Parks, biosphere reserves, etc.)

- Public administration (national, regional, local)

- Civil society actors (NGOs, forestry organisations, environmental, nature conservation, tourism, hunting, leisure, sport, other interest groups)

- Municipalities (local community, villages)

- Forestry industry (including sawmills and other major wood-processing, wood traders)

- Small or Medium Enterprises (SME) (e.g., (wood) craftsmen, carpenters, (wood)-designers, tree-nurseries)

- Networks for forestry or wood processing, federations of forest-/wood-related companies

- Consumers, including various types of tourists (day tourists, overnight tourists, hunters, youth organisations, ‘everybody’, locals)

- Scientific/Research organisations (universities, research institutes)

- Educational stakeholders (kindergartens, schools, universities)

- Tourism industry/enterprises

- Locals (using forests through collecting wood, fruits, mushrooms; for leisure and recreation; traditional use; religious use)

- Financial enterprises (e.g., banks, funding agencies; business support funds).

There are many ways to categorise and ‘sort’ stakeholders. For example, they may have different actual or potential roles with respect to the governance innovation (process) under scrutiny, being, for example, funders, implementers, or mediators/intermediaries. They may come from different societal spheres, such as public or state, private sector, and civil society; or they might be (actual or potential) beneficiaries of, or (negatively) affected by the governance innovation under scrutiny. Further, they might be situated and active at various spatial and administrative scales, such as local, regional, national, or perhaps even international; and some might even be active at several scales at the same time. Furthermore, they might be enablers of the governance innovation, or slow down and oppose the innovation (process). Finally, the different stakeholder groups might also hold different levels of power (resources) to influence the governance innovation and affect the innovation process.

Indeed, the first step of the Stakeholder Analysis is to identify those actors that are actually or potentially involved in or affected by the governance innovation in the respective Innovation Region and at what levels and different realms they operate.

- Some categories of stakeholder characteristics may refer to individual stakeholders, others more to the organisation, administration, or interest group they represent; sometimes both will be relevant, and perhaps distinct. Some of the characteristics might be directly related to the governance innovation, others might be more or less independent. If possible and appropriate for the individual Innovation Region, the analysis should shed light on the following characteristics for each type of stakeholder identified as relevant:

- Interests and motivations with respect to forest ecosystem services, forest governance, and the governance innovation (process)

- Actual or potential role and influence within his/her organisation, within forest governance and, if applicable, the governance innovation (process)

- Knowledge, competencies, educational background

- Power and other resources (including positional power, coercion, financial); control over resources

- How and to what degree affected by forest governance or the governance innovation (positively or negatively; politically, scientifically, financially)

- Forms and means of communication employed between relevant stakeholders

- Visions with respect to management and use of forest ecosystem services, forest governance, and the governance innovation (process)

- Concerns with respect to management and use of forest ecosystem services, forest governance, and the governance innovation (process)

- Differentiated rights to access and use forests and forest resources.

- There is a wide range of empirical tools and methods that can be used to identify, describe, and assess stakeholder interests, visions, and concerns. Empirical approaches for Stakeholder Analysis include identifying and analysing written sources, such as relevant published research, legal documents, planning materials, policy documents, etc. Considered as particularly fruitful are:

- interviews: these can be exploratory, open, semi-structured; with all or a selection of relevant stakeholders; face-to-face or by telephone;

- group interactions: focus group discussions, other kinds of workshops, meetings with practice partners,

- surveys, and

- Stakeholder Network Analysis: such a comprehensive method could be used in a complementary way if time and resources allow.

These approaches may be employed separately or in combination. Which empirical method(s) to choose, depends on several factors. These factors include: the time and personnel available for the analysis; the intended degree of detail and comprehensiveness of the results; the availability and quality of relevant previous stakeholder analyses; and the complexity of the stakeholder context.

2.4.3 Time scheduling for the Stakeholder Analysis in project context

| What | Who | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| Draft heuristic for each Innovation Team (stakeholder types and categories, analytical framework for stakeholder characteristics, and empirical methods suitable) | ||

| Discussion, revision of heuristic | ||

| Pre-final heuristics for Innovation Teams; Example: Fact sheet on Austrian case study (Eisenwurzen) (Appendix III) |

||

| Case-specific implementation plans, i.e., translation of heuristic in Innovation Region-specific plans for Stakeholder Analysis (iterative process) | ||

Carrying out Stakeholder Analysis at Innovation Region level

|

||

| Compiling the results of Stakeholder Analysis at Innovation Region level – draft Innovation Region report | ||

| Discussion, and perhaps revision of Stakeholder Analysis at Innovation Region level | ||

| Cross-Innovation Region comparison, typology, integration of biophysical and institutional mapping results (Stakeholder Analysis national and EU levels) – draft report |

2.5 Utensil 5: Governance Situation Assessment

What is this?

- Mapping: This tool shall give early orientation for carrying out the analysis of the governance situations, into which forest ecosystem services innovations may be placed.

- Process, situation, and change in focus: It combines a situational view on the constellation of stakeholders currently involved and their relations with the dynamic perspective of the prior, current, and future (planned, imagined, expected) developments.

- This heuristic builds upon the generic Stakeholder Analysis (cf. section 2.4 above), while now also emphasising the politics regarding what innovation shall be pursued and which role might be played by whom.

- It conceptually anticipates the SETFIS framework (cf. section 2.3 above), which is better usable at a later stage in the innovation trajectory when more knowledge has been gathered and the nature of the innovation has become clearer, thus has the role of a ‘SETFIS light’ or SETFIS starter-kit (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 3.1, Sorge & Mann 2019).

How to use it?

- Analysts should use this “heuristic” as a guideline to include all crucial dimensions of the starting situation. It is a lens for discovering the situation, not a ready-made explanation of what the case is.

- Answer the questions under topics 1-5 to assess the situation in direct view of preparing activities and meetings in the Innovation Region with the stakeholders. It helps to sketch the conditions under which any option for pursuing an innovation needs to be seen.

- Use the answers and your knowledge of the situation to develop or elaborate the scenarios for the CINA workshops (cf. sections 3.4 and 4.1). It anchors the CINA scenarios in the (political, business) reality (cf. InnoForESt Deliverable 4.2, Aukes et al. 2020a).

Limitations for use

- Since the Governance Situation Assessment heuristic implies concepts which are not necessarily common knowledge, it requires the assistance of experienced facilitators (in this project through WP5) in a number of intensive meetings with each Innovation Team. It is also useful to hold a short workshop, during which the approach is elucidated.

- The first version of the findings may require extensive commenting by the facilitators and some collaboration in order to achieve the right density of analysis. Templates will be developed for future use.

- Users may find the approach time consuming or too detailed. However, the usefulness of having this overview at hand may become visible only during the scenario writing, the discussion of the scenarios during the first CINA workshop, or even during the analysis of the workshop results.

Further suggestions about how to use this heuristic are explained in detail below (see Appendix II for the original fact sheet as used in the project).

2.5.1 Assessing the governance situation: topics

The following list is a set of guiding questions that should assist you to get a more comprehensive idea about the situation that characterises the innovation you are trying to tackle and foster in your Innovation Region.

We often look at complex relationships between actors, innovation ideas, institutional and economic conditions. Innovation is an ongoing process that does not lead to results at the push of a button. Governance can best do justice to this if the variability is taken into account by improving and developing unsuitable specifications (Kuhlmann et al. 2019).

Topics 1 and 2 are the link to the Stakeholder Analysis (section 2.4). We are speaking of the ‘forest ecosystem governance innovation’, in brief: “the innovation”. We are speaking of ‘actors’ in general, because it may be worth looking beyond the stakeholders already identified. It might be enough to describe the situation on one page per topic. Use more pages and be more detailed if convenient.

Topic 1: Actors

In the Stakeholder Analysis, the actors are mapped as such; here, the focus is on their roles and interests in the governance and policy-making process; so, what’s the actors’ political agenda in the broadest sense, etc.

- Which actors are currently involved in the innovation? (Just fill in a table, please; in order to avoid redundancy, you can refer to the Stakeholder Analysis for more detail)

- How do they perceive the innovation?

- How do they perceive other actors and the interactions with them?

- Are there actors who are purposely or unintentionally excluded from involvement in the innovation? If so, why?

Topic 2: Actor interactions

Emphasis here is on how actors play together and against each other; crucial to know regarding the political atmosphere.

- What is the general character of the interactions among actors? Are there long-standing business or policy relations or rather recent ones; are there (a) permanent, (b) temporary, (c) formal, (d) informal occasions or combinations of these, on which actors meet and interact? Which are they?

- Are relationships cooperative or competitive, asymmetrical or symmetrical (i.e., referring to aspects of power)? Are there relationships or interactions which are rather conflictual among specific actors; are there tensions, also very informal ones or on a personal level; if yes, which and among whom?

- Which issues do actors mainly discuss when they interact? What’s at the core when they talk to each other?

- Are there actor alliances that pursue or at least support the innovation – or such that work against it? Specify!

- Are there specific actor relationships which are more and which are less fruitful than others? Specify!

- How do actors deal with disagreements and conflict situations? Please give examples!

Topic 3: History of the innovation

You could use a timeline here, e.g., in the form of a table listing the main features of the process line-by-line.

- What is the innovation’s history: (a) main phases, (b) main events, (c) previous efforts, (d) drawbacks, (e) founding narrative or ‘myth’? Could you also characterise the process of change and innovation?

- Who initiated the innovation? How? Why, for which purposes and reasons? What was the first impulse for the innovation?

- How did the innovation come to be accepted as such by the involved actors?

- What were the main barriers and how (far) was it possible to overcome them?

- How has the actor constellation changed over time?

- How have changes in the social context of the innovation changed its course or made adaptation of the innovation necessary?

- How has non-forest ecosystem services governance changed? Has this made adaptation of the innovation necessary?

- Is the innovation based on any similar governance pattern somewhere else? Has it been derived up from a totally different context?

- Which are the main (and the secondary) physical and ecological conditions under which forest ecosystem services governance developed in the past in your case?

Topic 4: Current situation of the innovation

- Which activities currently constitute the innovation process?

- Which policy instruments are currently used (or associated with) the innovation?

- What is currently perceived as key problems now to take care of regarding the innovation in the Innovation Region (by the stakeholders)?

- In terms of some imaginary project life cycle, at what point has the innovation now arrived for the key actors? Same for all?

- Has the innovation so far produced any unintended side effects?

- Are there any parallel developments that are (more or less) competing with this innovation?

- How is the innovation perceived in its direct and indirect social environment: (a) overall public image/perception, (b) support, (c) critique?

- Which are the main (and the secondary) physical and ecological conditions under which forest ecosystem services governance currently functions (more or less well)?

Topic 5: Expected developments for the innovation

This could be core to the workshop scenario alternatives!

- Is the journey of the innovation presently seen rather open-ended or closed – according (a) to the main stakeholders’ views and (b) to your view as observers?

- Do you expect moments at which large choices have to be made which may (radically) influence the direction the project takes? If so, how would one know?

- Which problems with the innovation are perceived and which solutions are currently discussed (and which ones not?)

- Is the innovation part of or connected to a more general development in the broader landscape (trends, events, external pressures, etc.)?

- Which are the trends and directions towards which the main (and the secondary) physical and ecological conditions under which forest ecosystem services governance function?

2.5.2 Assessing the governance situation: the key problem structure

This part aims at identifying the problem structure of the case: the main struggles and agreements. If you know these, you basically address them strategically.

Look back into part 2.5.1 and collect the current key problem issues in the advancement of the innovation in your case studies. „[P]eople’s involvement is mediated by problems that affect them“ (Marres 2007: 759). They mobilise such problem issues and are mobilised through them when dealing with public affairs. Key problem issues are those aspects of the innovation or its context that are perceived and eventually communicated in the Innovation Region as to be taken care of. These problem issues likely refer to a set of obstructions that need to be tackled in order to advance the innovation. They may actually characterise the crucial dimensions of the innovation.

(1) In a first step, identify and summarise these issues:

- Make a list of all problem issues associated with the innovation (political, business, physical, cultural, technological, actors, etc., whatever you think characterises the state of affairs for the innovation for those involved), as found in section 2.5.1.

- Decide which are the most important ones (a) from local innovators’ viewpoints and (b) from an observer’s point of view.

(2) In a second step, describe each problem issue in terms of the ease or difficulty with which it can be handled.

- We suggest allocating the problem issues into four (one more or less) different categories.

- Please describe your problems in terms of their structure (see Figure 2.2; cf. Hoppe 2010).

Please, describe in your words how it makes sense to categorise each of the crucial issues in such a way (you can be as brief as you think it sufficient to understand also for case outsiders).

2.5.3 Problem categories

This section is supposed to elucidate how the figure on key problem issues works. The figure is based on what has been called the “governance of problems” and attempts to categorise types of problems depending on two dimensions:

- How much is known about the problem?

- How much do involved actors agree on the norms and values related to the problem?

To make this a little bit more concrete, we provide a similar figure including examples related to forest ecosystem services (Figure 2.3). These are just some examples. Based on your deeper knowledge and understanding of forest ecosystem services problematics you may as well categorise the examples differently. However, we hope, the figure can serve as a first hunch for how to describe “all issues associated with the innovation (political, business, physical, cultural, technological, etc., whatever you think characterises the state of affairs for the innovation)” in terms of their problem structure.

2.5.4 Time scheduling for Governance Situation Assessment in project context

| What | Who | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| Heuristic for case study partners | ||

| Discussion, revision of heuristic | ||

Governance Situation Analysis on Innovation Region level

Draft reports (in order to be able to link this with the Stakeholder Analysis) |

||

| Governance Situation Analysis on Innovation Region level Final drafts (in order to be able to use this for preparing the strategic workshops) |

||

| Discussion, (if necessary) revision of Governance Situation Assessment | ||

| Final reports | ||

| Cross-Innovation Region comparison, typology, integration of biophysical and institutional mapping results (Stakeholder Analysis national/EU levels) Navigator (Interim version) |

2.6 Utensil 6: Idealised Innovation Process

The Idealised Innovation Process is the overarching concept pulling together InnoForESt’s multi-stakeholder, scenario-based innovation process, which allowed us to analyse, develop and foster forest ecosystem services governance innovations for sustainable forest/natural resources management and ecosystem service provision (see Figure 2.4). You will find the detailed description of each Idealised Innovation Process element in dedicated sections below.

What is this?

Activities that helped analysing, developing and fostering innovations for sustainable futures consist of three sub-processes that were closely linked to each other (Figure 2.4):

- Establishment of Innovation Platforms: through these platforms, InnoForESt offered meeting places for communication, knowledge exchange and common activities, such as seminars or workshops (see section 3.1 for more detail).

- Innovation Network activities: involving partners in the region that help foster innovation and carry the innovation forward through the negotiation of aims and processes, collaboration and exchange (see section 3.2 for more detail).

- CINA Workshops: Networks became involved in a series of workshop activities in the Innovation Regions. Case-specific scenario narratives were the main input. The workshop series consisted of three core types that are an integral part of innovation action: Innovation analysis and visioning, Prototype assessment, Preparing future conditions (see sections 3.3, 3.4 and 4.1).

How to use it?

The establishment of platforms was the essential structure required for the process facilitation. This requires a functioning work and meeting space and sufficient devoted time by the process manager. Once this was set-up, stakeholder engagement and networking activities started to form a group of committed partners for further advancing the innovation ideas and preparing them for the structured CINA process. Here, it was important that all these three CINA workshop types (Innovation analysis & visioning, Prototype assessment, and preparing future conditions) occurred in each application context. However, the implementation very much depended on the context, so decisions about which types to emphasise when had to be taken by the local innovators themselves. This implied that combinations of these types in one or more workshops were possible, as well as further innovation activities, workshops, etc.:

- Adaptation is crucial. Each application context differs in terms of innovation type, context conditions and innovation development stage.

- It is of crucial importance to adapt the idealized innovation process to the specific context and needs of the case study, when applying the three core elements of platform, network and workshops.

- It is important that stakeholder interests are closely incorporated in the innovation process, providing as much room and freedom for own ideas as possible.

- Keep the availability of support products in mind and make sure the core elements of workshop content are part of the process. This is important to allow for interaction and exchange.

Limitations for use

- It requires resources to set up and run innovation platforms, foster network establishment, management and workshop conduct.

- It also requires trained personnel (InnoForESt training material available on www.innoforest.eu).

- And it requires dedicated participants. The more the innovation activity is in line with stakeholder interests, visions and demands, the more involved over time they can be.

2.7 Utensil 7: Innovation Journey reconstruction and use

In research on corporate innovations, the concept of an ‘innovation journey’ had been developed to make innovation more tangible: to view an innovation not solely as a product, but as a process. While forest ecosystem services governance develops and uses policy instruments and struggles with their revision, reinvention or replacement under often changing circumstances, our particular focus on the innovation journeys is a novelty. We suggest an elaborated innovation journey concept tailored to the field of forest ecosystem services governance (cf. InnoForEst Deliverable 4.3, Loft et al. 2020).

With an approach that emphasises the co-evolutionary character of the process and its context we aimed to avoid a common misunderstanding, i.e., that innovation processes are a matter of control, steering and management (cf. Van de Ven 2017) – the “command and control approach”, as Rip (2010) puts it. Rather, when taking a closer look at the contingencies during innovation, retrospective attributions of success to certain approaches or persons often prove to be misleading. Thus, we suggest to imagine innovation as a journey into uncharted waters (Van de Ven et al. 1999: 212). In order to achieve anything, managers and policymakers “are to go with the flow – although we can learn to manoeuvre the innovation journey, we cannot control it” (Van de Ven et al. 1999: 213). For this reason, we developed an empirically grounded and theoretically informed conception of the innovation journey that “captures the messy and complex progressions” while travelling (Van de Ven et al. 1999: 212-213). This allowed us to describe the uncertain open-ended process by reconstructing precisely the open ends and uncertainties, the more or less organised social actions and negotiations, and to identify patterns and typical key components. At the end of the day, apart from its scientific contribution, this kind of information may be exactly what policy-makers and practitioners need when navigating along uncharted rivers in their own efforts to pursue a governance innovation.

What is this?

- Innovation Journey: a conceptual approach from innovation studies that regards an innovation not solely as a product, but as a process.

- The reconstruction of an Innovation Journeys is the description and analysis of the development of innovation processes along a set of event categories.

- This analysis focuses on the niche innovation but also considers its socio-technical context by taking into account the socially enacted interactions between the niches, established regimes as well as other socio-cultural, economic and political landscape developments and trends, against the background of which the more specific dynamics of particular regimes and niches evolve.

- Applied in InnoForESt it provided the grounds for a comparable analysis of the innovation developments within our Innovation Regions.

How to use it?

- Analysts should apply the adapted concept as a guideline to include all crucial events in the innovation development process.

- It provides an understanding of the innovation process. In particular, it helps to analyse and reflect on reasons for certain turns in the development process.