Deliverable 4.3: The emergence of governance innovations for the sustainable provision of European forest ecosystem services: A comparison of six innovation journeys

| Work package | WP4 Innovation platforms for policy and business | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deliverable nature | Report (R) | |||

| Dissemination level (Confidentiality) | Public (PU) | |||

| Estimated indicated person-months | 12 | |||

| Date of delivery | Contractual | 30 October 2020 | Actual | 30 October 2020 |

| Version | 1.0 | |||

| Total number of pages | 82 | |||

| Keywords | Forest Ecosystem Services, governance, innovation, innovation journey, European Union |

|||

Executive summary

With this study we assess the process of developing novel niche innovations for sustainable forest ecosystem services governance. We chose a comparative qualitative analysis approach and conceptually built on, transfer and adapt insights from innovation research. In particular, we conceive of innovation as a process or a journey and not solely as a product. Our conceptual approach further acknowledges the need for taking into account the socio-ecological-technical context. We thus include a focus on the socially enacted interactions between niches that offer particularly fruitful innovation potential, established regimes as well as other socio-cultural, economic and political landscape developments and trends, against the background of which the more specific dynamics of particular regimes and niches evolve.

The Innovation Journeys are being reconstructed as an opportunity to get an overview of the mechanisms and dynamics of the innovation processes themselves. We proceed in an abductive manner, instead of a deductive-nomological logic. That is, both theoretical and empirical considerations flow into the structure and execution of the analysis. We emphasise that the methodology does not follow the theoretical assumptions, but the latter have developed in the light of the examination of the empirical material. The analytical categories for assessing and structuring our innovation processes have not been set in advance, but were developed with a view to the structure of the cases from the material analysis and partly, where appropriate, from the combination of different theoretical streams.

We find that (1) innovation development does not take place in isolated space. Rather, it is shaping and shaped by essential context conditions. (2) For innovation development the strategic orientation, i.e., the overarching aims and objectives are essential. (3) We highlight how regional innovations have been organized. (4) In the InnoForESt project, a process structure of measures was jointly developed, which provided for a number of measures to take place everywhere, such as three different types of CINA workshops. In addition, there were activities that were simply necessary to set the work process in motion in the regions. (5) Real world innovation development does not take place under ideal “laboratory” conditions. Rather it is shaped by problems, crises, stagnation and setbacks.

A closer look at the Innovation Journeys has revealed that (1) innovation processes have a rhythm, (2) which is very different depending on the local and historical situation in which it is embedded, (3) which is not simply going into the direction of the new, towards progress and (4) that stakeholder networks develop along with the rhythm of the innovation process. In addition, the role of the Constructive Innovation Assessment with its multi-phase approach became clearer.

Much has been achieved in the Innovation Regions during the course of the project by the Innovation Region Teams. In many cases, however, a quiet fading out was observable towards the end of the project, Partially due to the difficulties of meeting under Covid-19 conditions. At this stage it is up to the stakeholders themselves and the regional practice partners to decide whether they feel at ease or in a position to continue what they have achieved so far. The innovation work done is a good start, but still not enough for an innovation to fully take root.

In order to secure the legacy, stakeholders should initiate more meetings, either on invitation of the practice partner or of one of the stakeholders willing and able to organize an invitation and setup. Keeping in touch with the entire stakeholder network enables to stay up to date with further developments and with external relations and development influencing the innovation. At least regular meetings should enable to keep relationships vivid and to further debate on promising ways to secure achievements and ideally to keep on elaborating the innovation. The established digital platforms with its external and internal parts are ready to be used as technical support for information exchange and keeping the momentum alive.

List of figures

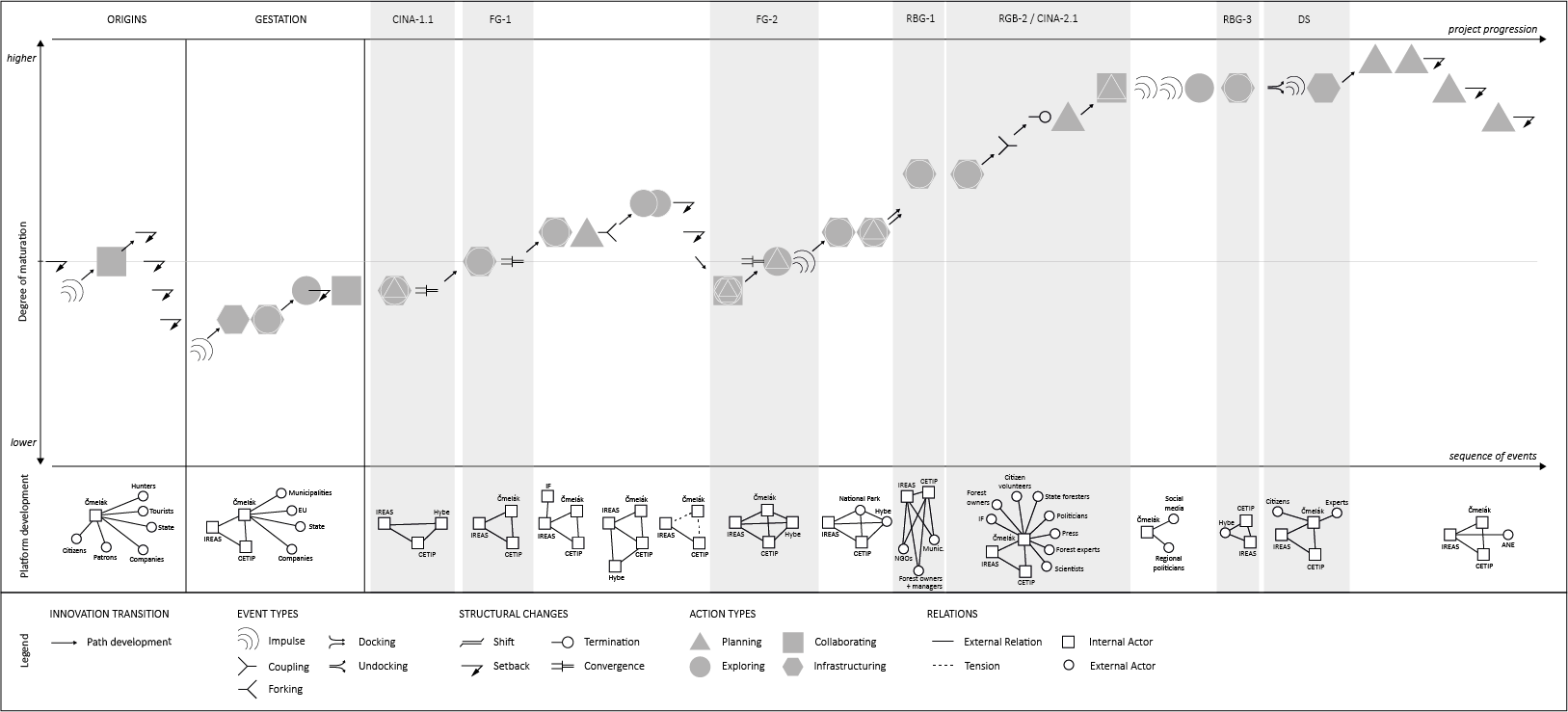

- Figure 1: Stylized approach of data collection and analysis

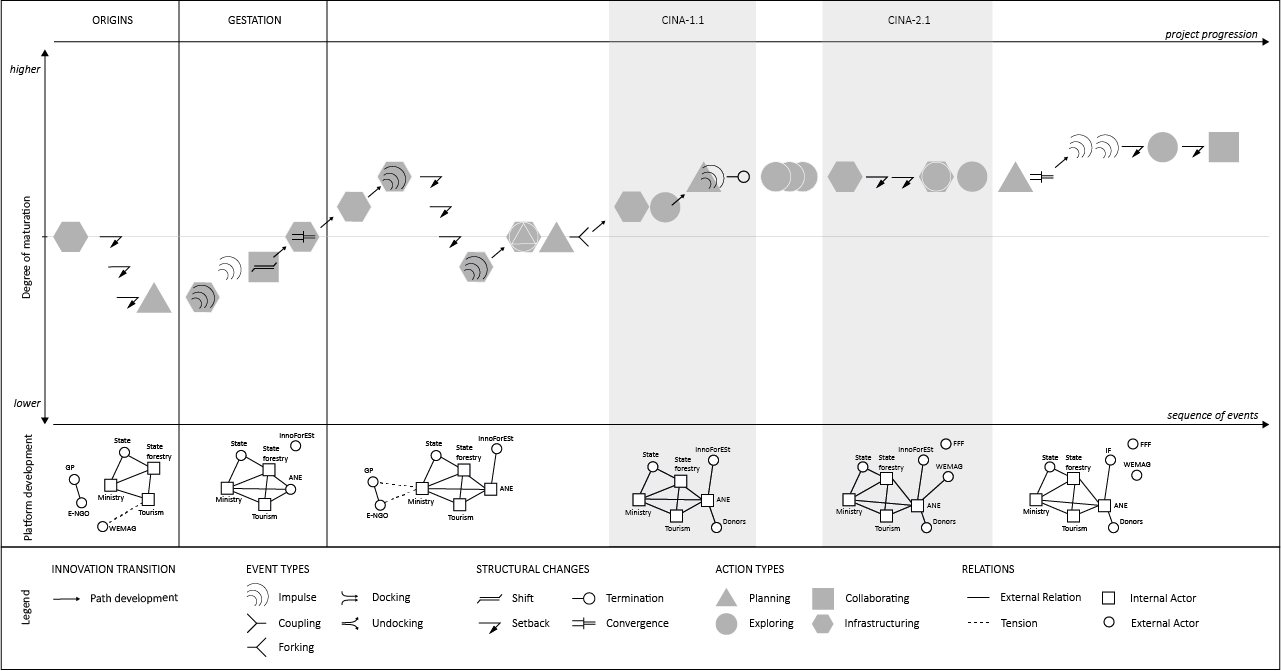

- Figure 2: Innovation Journey Eisenwurzen Forest-Wood value network

- Figure 3: Innovation Journey Habitat Bank of Finland

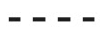

- Figure 4: Innovation Journey Love the Forest

- Figure 5: Innovation Journey Forest share payment scheme

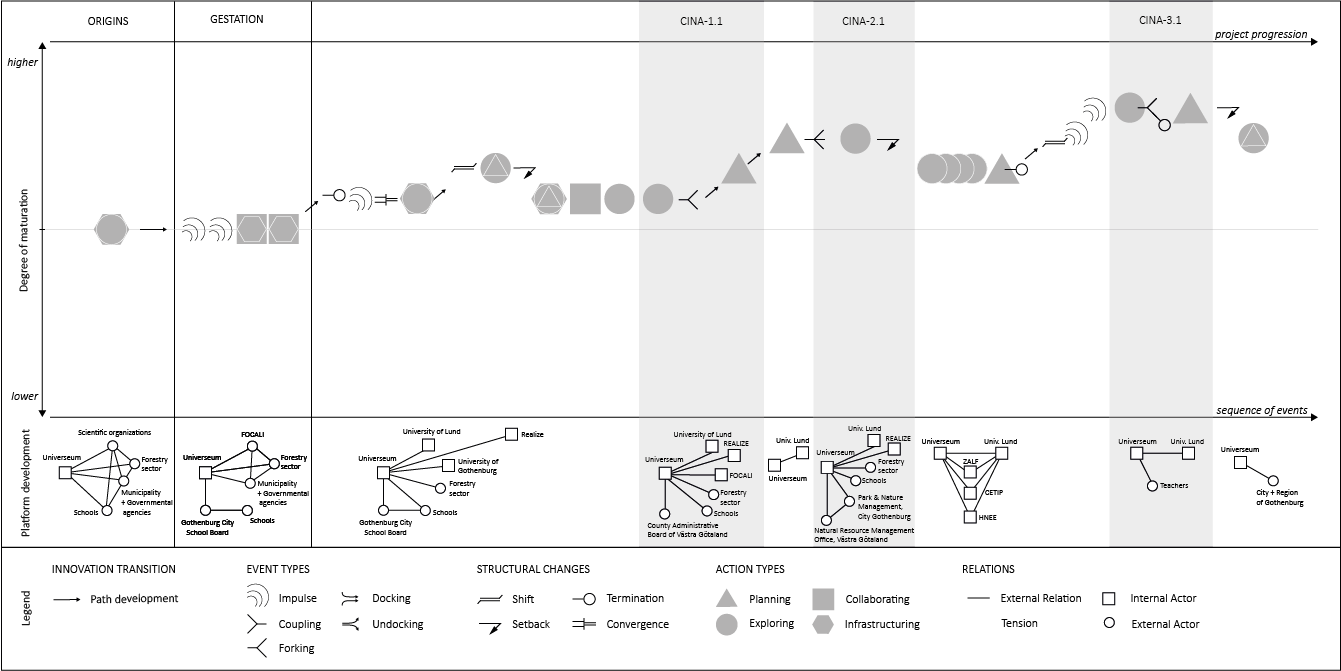

- Figure 6: Innovation Journey Fiera di Primiero forest-pasture management

- Figure 7: Innovation Journey Collective forest self-governance

List of tables

- Table 1: The heuristic categories used to describe forest ecosystem service governance innovation journeys

- Table 2: Type and number of CINA workshops carried out

Abbreviations

| AC | Alpine Club |

| ANE | Academy for Sustainable Development Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania |

| ARGE S’HOIZ | Working group wood from the community of Sauwald |

| BO | Breeder Organisation |

| CINA | Constructive Innovation Assessment |

| CETIP | Centre for Transdisciplinary Studies |

| Čmelák | Čmelák Land Trust Association |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| Covid-19 | Corona Virus Disease 2019 |

| D1.1 | Deliverable and respective number |

| DS | Discussion Seminar |

| E-NGO | Environmental Non-Governmental Organisation |

| EAFRD | European agricultural fund for rural development |

| EKOTEKO | Habitaattipankki tutkimuskonsortio (Habitat Bank research consortium) |

| EU | European Union |

| EU H2020 | Europen Union Horizon2020 |

| FES | Forest Ecosystem Service |

| FFC | Finish Forestry Centre |

| FF | Freelance Forester |

| FFF | Fridays for Future |

| FG | Focus Group meeting |

| FIBS | Finnish organization; promoting sustainable business |

| FO | Forest Owner |

| FOCALI | Forest, Climate, and Livelihood research network |

| FOREST-SME | Forest related small-medium enterprises |

| FD | Forest District |

| FS | Forest Service |

| FSC | Forest Stewardship Council |

| GP | Green Party |

| HNEE | University for Sustainable Management Eberswalde |

| HA | Hunters Association |

| HO | Hotel Owner |

| Hybe | Hybe Land Association |

| IF | InnoForESt project |

| IKEA | Ingvar Kamprad Elmtaryd Agunnaryd |

| INNO-1 | Innovation focus groups (1-4) |

| INTERREG | Program funded by the European Regional Development Fund |

| IR team | Innovation Region team |

| IREAS | Institute for Structural Policy |

| HSBC | Hongkong & Shanghai Banking Corporation Holdings PLC |

| L | Landscape |

| LEADER | Long-Term Social-Ecological Research platform Eisenwurzen |

| LTSER | Long-Term Social-Ecological Research platform Eisenwurzen |

| LUMACON | Lumacon Holztechnologie GmbH |

| METSO | Forest Biodiversity Programme for Southern Finland |

| MHC | Möbel und Holzbau- Cluster |

| MLP | multi-level perspective |

| Munic. | Municipality |

| NC | Nature Conservationists |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisations |

| NP | National Parks |

| PAT | Autonomous Province of Trento |

| PF | Private Farmers |

| PL | Private Landowners |

| REALIZE | Workshop facilitation organization |

| RBG | Role Board Game |

| SEC | Institute for Social Ecology |

| SETFIS | Socio-ecological-technical forestry innovation system analysis framework |

| SO | Sawmill Operator |

| SPES | Studiengesellschaft für Projekte zur Erneuerung der Strukturen |

| STUDIA | Study Group for International Analysis |

| SYKE | Finish Environmental Institute |

| TB | Tourist Board |

| UIBK | University of Innsbruck |

| Univ. Lund | University of Lund |

| UNITN | University of Trento |

| ÜBERHOLZ | Wood design training course “Überholz” at the University of Art and Design Linz |

| WEMAG | Westmecklenburgische Energieversorgung AG |

| WS | Workshop |

| ZALF | Leibniz-Zentrum für Agrarlandschaftsforschung |

1 Introduction

European forests have multiple functions and provide a range of forest ecosystem services to society (García-Nieto et al., 2013; Plieninger et al., 2013; Saarikoski et al., 2018). However, during the past decades, the objective of professional forest management systems has mainly been focused on timber and biomass production with an emphasis on increasing the efficiency of forestry, resulting in standardized forestry practices and uniform forest structures, even when the policy goals have been more multi-functional (Puettmann et al., 2009; Sutherland and Huttunen, 2018; Aggestam et al., 2020). Coinciding with intensified primary production processes, climate change, biodiversity loss, increasing urbanisation and pandemics outbreaks, societal demand has grown for the broad range of benefits that forests provide, in particular regulating and cultural forest ecosystem services, such as habitat provision, carbon sequestration and recreation. This has resulted in shifting emphases in forest management approaches and policy objectives towards sustained flows of goods and services, beneficiaries’ values and ecological functions (e.g., Bauhus et al., 2017; Grassi et al., 2017; Wolff et al., 2015).

The public good and common pool resources character of many forest ecosystem services (e.g., Farley and Costanza, 2010; Agrawal, 2007), institutional mismatch, different ownership structures, and insufficient information on demand and supply, governing the range of forest ecosystem services pose challenges for institutional adjustments. Furthermore, the forestry sector is shaped by a range of forest-related policies outside the forestry sector, such as agriculture, energy, biodiversity and nature conservation, climate protection, and rural development (e.g., Edwards and Kleinschmit 2013; Winkel and Sotirov 2016). These sectors and their formal systems of rules are only marginally aligned, leading to conflicts in objectives and management decisions for forest ecosystem services provision (Hauck et al., 2013). Overall, this calls for new and innovative approaches for actor and market coordination.

In the past decades, novel governance approaches emerged throughout Europe that support the provision of non-marketable forest ecosystem services, especially for regulating and cultural forest ecosystem services or bundles thereof. These include for example changing silvicultural practices to more close-to-nature management (e.g., Puettmann et al., 2009; Bauhus et al., 2017), the establishment of collaborative forest owner associations (Agrawal et al., 2008) or the setup of certification systems and the design of payment schemes for ecosystem services (Živojinović et al., 2015). Often these governance approaches emerge as pilot studies at local level. Some of them proved to secure conservation and social functions of forests, and were able to provide alternative income streams for forest owners (e.g., Živojinović et al., 2015), while for many other governance approaches a systematic evaluation of their design, implementation and outcomes are missing (e.g., Miteva et al., 2012; Vatn, 2009). In particular, it remains unclear how such novel and innovative modes of ecosystem service governance successfully emerged, which parameters constrain and enable their development process.

With this study we aim to contribute towards closing this knowledge gap by assessing the process of establishing / developing novel niche innovations for sustainable forest ecosystem services governance. We chose a comparative qualitative analysis approach and conceptually built on, transfer and adapt insights from innovation research. In particular, we conceive of innovation as a process or a journey and not solely as a product (Van de Ven et al. 1999; Kuhlmann, 2012). Our conceptual approach further acknowledges the need for taking into account the socio-ecological-technical context. We thus include a focus on the socially enacted interactions between niches that offer particularly fruitful innovation potential, established regimes as well as other socio-cultural, economic and political landscape developments and trends, against the background of which the more specific dynamics of particular regimes and niches evolve (Geels 2002; Geels and Schot 2007; Rip 2012; see section 3 for more detail).

The study is structured as follows: in the subsequent section we provide some background to the study context and the case selection, i.e., the EU H2020 InnoForESt project in the context of which forest ecosystem service governance innovations were (further) developed and assessed. In section 2, we state our case selection. In section 3, we describe our methodology. Section 4 details the Innovation Journey concept, i.e., it theoretical-conceptual foundations and the way in which we have further developed it. Section 5 then presents the innovation processes analysis of our six cases, followed by a discussion of the transversal/cross-cutting findings in section 6. We discuss this in section 7 and provide an outlook in section 8.

2 The InnoForESt project and case selection

We conduct this study in the context of the InnoForESt project (https://innoforest.eu/). InnoForESt is a European Horizon 2020 funded -Innovation Action. Its objective is to stimulate governance innovations for the sustainable supply and financing of forest ecosystem services. The project supports the emergence, development and mainstreaming of new payment schemes and business approaches as well as novel actor constellations and networks for forest ecosystem services provision through multi-actor assessments, networking activities, prototyping of good innovation practices and transdisciplinary research. Its outcomes are directed to boost governance innovation activities and to support future forest policy making, management and business, from regional to EU level.

The project aims to facilitate the understanding, improvement, transfer and/or up-scaling of governance innovations for sustainable forest ecosystem services provision. Such innovations respond to a growing demand for sustainable governance of forest ecosystems steered by awareness-raising initiatives at the European and national levels. By demonstrating the functioning of alternative financing mechanisms and actor cooperation, incentives for forest owners and administrators to supply non-market forest ecosystem services are provided.

InnoForESt’s is conceptually and methodologically rooted in innovation research, complex system thinking and multi-actor approaches. It accounts for, and acknowledges, regional differences with regard to forest ecosystems, ecosystem services provided, contributions to the economy as well as institutional landscape and stakeholder constellations. To take these context particularities into account, promising governance innovations are thoroughly analysed in a holistic way, optimised, maintained, and constructively put into future application scopes. The research and implementation is organised in six so-called Innovation Regions (IR), situated in Austria, Finland, Germany, Italy, in both Slovak, and Czech Republics, and Sweden, each differing in social-ecological-technical forest and forestry conditions. The six Innovation Regions represent a range of biogeographical regions of European forests (i.e., Atlantic; Continental; Boreal; Alpine, Mediterranean), forest ecosystem services types (provisioning, regulating, cultural, and combinations of those), as well as forest governance and business environments. Being closely shaped by the regional settings, they serve as loci for learning for particular types of governance innovation. These governance innovations are either payments for ecosystem services (Forest Share or “Waldaktie”, in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania Germany; “Habitat Bank of Finland”, Finland), new business approaches (“Value Chains for Forests and Wood”, Eisenwurzen, Austria), or new actor constellations and networks (“Forest Pasture System Management”, Trentino, Italy; “Collective governance of Ecosystem Services”, Liberec region, Czech Republic and in Hybe, Slovak Republic; “Love the Forest”, in the Gothenborg area, Sweden). Studying and assisting further innovation developments, InnoForESt cross-compares their co-designs’ effectiveness and effects, and further developing strategies that smartly incentivise the provision of forest ecosystem services as bundles in a context-sensitive and desired, hence sustainable way.

InnoForESt project activities in each Innovation Region have been managed by a team consisting of a local science and practice partner. While the science partner focused on coordination of in-country implementation of research tasks, the practice partners have been responsible for the operational management of innovation activities. These include network formation and maintenance from local to national level, related data collection, innovation assessments, visioning and road-mapping. Innovation Regions function as central hubs for network formation, and to carry out innovation activities. The stakeholder networks and teams of science and practice partners in each Innovation Region have been connected to, and exchanged with, teams from further Innovation Regions. This provides the possibility to successively enlarge innovation networks to inter-regional, national and EU level for common exchange, learning and consultation. Over the project lifetime, they act as regional nuclei for extending the innovation approach and its application to other regions and levels of governance (interregional, national, EU).

As such, InnoForESt supports the development of sustainable business and network opportunities, diversifies the forest ecosystem based goods and services, and maximises their positive ecological, social and economic impacts. This will lead to the more coordinated, efficient and sustainable governance and financing of forest ecosystem services in Europe and therefore, to the well-being of EU citizens and the ecological integrity of forest ecosystems.

3 Methodology

In this study we proceed in an abductive manner, instead of a deductive-nomological logic. That is, both theoretical and empirical considerations flow into the structure and execution of the analysis. We emphasise that the methodology does not follow the theoretical assumptions, but the latter have developed in the light of the examination of the empirical material. The analytical categories for assessing and structuring our innovation processes have not been set in advance, but were developed with a view to the structure of the cases from the material analysis and partly, where appropriate, from the combination of different theoretical streams.

3.1 The reconstruction of the Innovation Journeys: data collection, analysis and visualization

For each Innovation Region Innovation Journey, the data collection was based on a four-stage approach: In phase 1, we reviewed all reports and other forms of documentation of the innovation processes that had been produced since the beginning of the project in October 2017 until the beginning of March 2020. This included the reports on the Constructive Innovation Assessment (CINA) workshops (Aukes et al. 2020), various project memos, audio recordings of project meetings and relevant existing interviews with practical and scientific partners (see Annex A-D). Based on this, in phase 2, we completed the data collection by designing and conducting open narrative group interviews with teams of each of our six Innovation Regions, consisting of scientific and practice partners (see Annex A for Interview schedules and participants). The interviews were carried out in April and May 2020. Due to the Europe-wide Covid-19 lockdown measures at that time, interviews were carried out via video conference platforms instead of the planned face-to-face interviews. In phase 3, based on the empirical information generated in the first two steps, we compiled a document that contained a preliminary chronology and categorization of relevant activities and events, and asked the partners in the regions to correct, complement and validate the resulting documentation. Furthermore, Innovation Region teams were then asked to highlight key activities and events. On this basis, we discussed the resulting changes with each Innovation Region team in another online meeting. Finally, in phase 4, this compilation was condensed into an analytical innovation Journey for each Innovation Region and validated by the Innovation Region Teams (see section 4 below). The latter process was combined with a graphical design of the innovation journeys, which resulted in a continuous alignment and reflection of the path development, the degree of innovation maturation as well as the platform development in the respective stages.

3.2 Conceptual aspects

Our conceptualisation builds on existing frameworks for innovation journeys (Van de Ven et al. 1999; Voss 2007). We carefully adapted these concepts to our setting of forest ecosystem services governance innovation processes by probing categories from Van de Ven and Voss with one of our innovation cases, the Innovation Region Eisenwurzen, as a pilot. All categories have been further developed and tailored for our specific subject area (see section 4 below). This was again carried out in close collaboration with researchers of the Eisenwurzen Innovation Region Team and who had good knowledge about the details and dynamics of the innovation process. In comparison to Van de Ven et al. 1999 and Voss 2007, this led to a more specific and expanded list of analytic categories. Our set of analytical categories takes into account the particular interactions between the innovation processes and their socio-technical contexts, which are characteristic of the respective innovation journeys (see Table 1 in section 4.2). As soon as the adapted heuristic (Abbott 2004; Kleining 1995) had become sufficiently detailed and helpful to structure and categorize all relevant activities and events and to arrive at a comprehensive result, we used it to interpret a second case, the IR Trentino, while further extending and refining it. This allowed us to further adjust our set of analytical innovation process categories. During the subsequent analysis of the remaining cases, we further fine-tuned the heuristic. Following an abductive research logic (Reichertz 2007) this ultimately resulted in a generalised heuristic for innovation journeys commonly applied to all our six cases.

4 Theoretical focus: the Innovation Journey concept

4.1 Starting points and basic assumptions

In research on corporate innovations, Van de Ven et al. (1999) developed the concept of an ‘innovation journey’ to make innovation more tangible: to view an innovation not solely as a product, but as a process (Kuhlmann, 2012). In their initial version, Van de Ven et al. (1999) proposed a list of twelve process events to categorize the – sometimes quite unpredictable – development of innovation processes. In innovation studies, the concept was then taken up and further developed in order to counter a crucial disadvantage of the concept in its original form: the disregard of the organizational environment and the restriction to a company-related, purely internal view of innovation (cf. also Geels 2014). The resulting multi-level perspective (MLP) added a socio-technical context to the business perspective by focusing on the socially enacted interactions between niches that offer particularly fruitful innovation potential, established regimes as well as other socio-cultural, economic and political landscape developments and trends, against the background of which the more specific dynamics of particular regimes and niches evolve (Geels 2002; Geels and Schot 2007; Rip 2012).

Complementary, Voss (2007) further focused his adapted concept of innovation journeys on the “duality of social process as captured in pairs of terms like design and dynamics, management and politics or planning and (co-)evolution” (Voss 2007: 5) with regards to policy instruments of “emission trading” and “network access regulation” that are “embedded in broader co-evolutionary processes” (ibid.). While forest ecosystem services governance develops and uses policy instruments and struggles with their revision, reinvention or replacement under often changing circumstances, our particular focus on the innovation journeys is a novelty. The concept of a journey in innovation has early been used only metaphorically by Lovins et al. (1999), although not in a conceptual sense, for companies as “journeys toward natural capitalism” (Lovins et al. 1999: 148), and later by other authors speaking of journeys toward landscape sustainability (Wu 2013), community-based forestry (Paudyal et al. 2017), and social license to operate (Wang 2019). We suggest an elaborated innovation journey concept tailored to the field of forest ecosystem services governance.

With an approach, that emphasises the co-evolutionary character of the process and its context, we aim to avoid a common misunderstanding, i.e., that innovation processes are a matter of control, steering and management (cf. Van de Ven 2017) – the “command and control approach”, as Rip (2010) puts it. Rather, when taking a closer look at the contingencies during innovation, retrospective attributions of success to certain approaches or persons often prove to be misleading. Thus, following Van de Ven, we suggest to imagine innovation as a journey into uncharted waters (Van de Ven et al. 1999: 212). In order to achieve anything, managers and policymakers “are to go with the flow – although we can learn to manoeuvre the innovation journey, we cannot control it” (Van de Ven et al. 1999.: 213). For this reason, we developed an empirically grounded and theoretically informed conception of the innovation journey that “captures the messy and complex progressions” while travelling (Van de Ven et al. 1999: 212-213). This allows us to capture the uncertain open-ended process by reconstructing precisely the open ends and uncertainties, the more or less organised social actions and negotiations, and to identify patterns and typical key components. At the end of the day, apart from its scientific contribution, this kind of information may be exactly what policy-makers and practitioners need when navigating along uncharted rivers in their own efforts to pursue a governance innovation.

While not going into detail of the original categories by Van de Ven et al. (1999) and the adapted categories by Voss (2007), in the following section (4.2), we briefly point out the specific features of our further developed set of innovation processes analysis categories.

4.2 The adapted innovation journey framework

With the help of two particularly dense and detailed documented innovation cases from our project portfolio (Innovation Regions Eisenwurzen and Trentino, see section 5 below), we adapted the innovation journey frameworks from Van de Ven et al. (1999) and Voss (2007) to the special features of our forest ecosystem services cases. Where necessary, we adjusted definitions of existing categories and introduced additional categories. The aim of the category set for the innovation journey is to describe the spectrum of crucial structural events and relationships through generalisable and comparable analytical categories. The structural events and relationships were previously reconstructed empirically, as explained in the method section above (see section 3.1). There are numerous documentations of the innovation process elements and self-reflections by the Innovation Region Teams and others involved, that have been produced during the course of the project, i.e., since October 2017. The structure of the course of the innovation work and the circumstances of the same has been created on the basis of these sources and has been discussed intensively with the partners in the regions in order to be able to correctly assess relationships and include backgrounds. Table 1 lists the categories and their definitions from which the heuristic is made up. In the following, we have already included a number of examples from all six cases for better understanding. We have inserted a row with symbols for some categories as we have visualized with a figure for each of the resulting Innovation Journeys in section 4.

| Analytical category | Definition (in the context of the InnoForESt project) | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| Phases | ||

| Origins | Pre-history of the innovation journey (prior to the preparation phase of the InnoForESt project) | (None) |

| Gestation | Initiation phase: informal beginning of the innovation project work (tentative during preparation phase starting with the proposal writing process until the formal project start in November 2017) | (None) |

| Project progression | Main innovation journey: formal innovation project work within the InnoForESt framework | (None) |

| InnoForESt key action types | ||

| CINA workshops | Workshops with a variety of stakeholders who act as the linchpin of innovation work; to articulate strategies and needs in crucial phases of regional innovation efforts; used both to probe alternative scenarios and to collaboratively find binding directional decisions that stakeholders are satisfied with | (None) |

| CINA type 1 | Workshop to articulate needs and strategies with the aim of developing and deciding on viable and exciting options for innovation | (None) |

| CINA type 2 | Workshop for the early review of how a selected innovation approach and object develops (in other places we also say: assessment of a prototype) | (None) |

| CINA type 3 | Workshop in which strategies are developed in order to be able to continue the innovation work started even after the end of the project | (None) |

| SETFIS interviews | Opportunity to discuss the decisive factors influencing the innovation with key players (also the objective in the context of InnoForESt), which results in intense moments of reflection, stakeholders are actively involved and at the same time assessments of the situation from other Innovation Regions are offered for inspiration; can ultimately even contribute impulses to a reconfiguration of innovation in a region | (None) |

| RBG | Role-play with rational decision-making problems that have been used where appropriate to sensitize the stakeholders to key issues of forest use | (None) |

| NetMap | Interviews conducted at different moments in an innovation process to determine the actor constellations | (None) |

| Event type | ||

| Planning | Project plans are being developed (action), including decisions for future action; the emphasis is on the organisational character of the work |  |

| Exploring | Acquisition of useful knowledge about the people and the region involved as a basis for further activities and to build relationships (action); includes any learning effort, that is newly to the innovation work at the specific point in time or by using existing stocks of knowledge or knowledge from other sources |  |

| Infrastructuring | Building of the platform and network (action) Focus is on building / developing / stabilising the network, a meeting or a collaboration, i.e., the structure; extension or shrinking of stakeholder circle / network; inviting moderators |

|

| Collaborating | Tackle/work/act together and set something in motion (action) Focus is on content: a regional team and other stakeholders take action together and jointly and do something that goes beyond the usual process that the innovation team organizes something for the stakeholders (action); more than just sitting together and talking with more or less agreement, or than organising a workshop or platform building |

|

| Docking Undocking |

External events/projects/activities in relation to a given innovation effort temporarily join the innovation project for the time being, then either integrate or go separate ways again External efforts to hook up, such as the “satellite workshop” on a potential fourth innovation idea in Eisenwurzen; not yet integrated, or perhaps never will be |

|

| Forking Coupling |

Development of two or more ideas for scenarios out of a more general idea Conjunction of scenario ideas (potentially scenario selection) This applies to Innovation Region Team or InnoForESt project internal integration or differentiation, the focus is on scenarios and ideas |

|

| Impulse | Positive or negative event with an impact/impulse on the development direction Critical event, e.g., shock, crisis, push; incremental or radical, external or internal; only such of higher relevance |

|

| Shift | Change of focus regarding criteria, problem framing, participating personnel, aims and objectives, etc. (not per se a change of maturation level) |  |

| Process changes | ||

| Setback | Includes mistake, stagnation, crisis, severe doubt, deadlock, obstacles, and describes their effect due to both external or internal circumstances Focus on the innovation, which suffers from a setback: consequences of strong and various setbacks may degrade the level of maturation |

|

| Termination | Any deliberate termination at any time on content level (actors leaving or kicked out, scenario/theme ending, plans/ideas, path break-up, etc.) |  |

| Convergence | Aligning of new and old, or parallel projects, InnoForESt project and competitive projects |  |

| External Relations | External actors come in/play a punctuated role; no continued collaboration, only selective mutual reference in action |  |

| Tensions | Disagreement, mismatch, strongly drifting apart about knowledge or value basis, political/economic aims or interests (e.g., with external actors or others) |  |

| Range of the event / happening | ||

| Regime | When a niche process or event interacts with the incumbent regime development | R |

| Landscape | When a niche process or event interacts with the broader landscape development | L |

| Level of maturation | Relative degree / level of the specific innovation tendency in terms of progressive, constant (stagnation), or regressive development of the entire configuration of relevant actors and other elements (resources, commitment) | (None) |

- First, we have identified a number of ‘events’ that give direction to an innovation. These can be strategically significant actions or events in the narrower sense, i.e., occurrences that relate to a point in time.

- Second, we distinguish a number of ‘process changes’ associated with these events. This means which direction the innovation work is taking, which obstacles arise, and how this work relates to other innovations that take place in the relevant area but do not belong to the project.

- Thirdly, we divide each innovation process into chronological ‘phases’, during the course of the project (project progression) and the previous developments (origins, gestation).

The analysis focuses on the niche, in which the innovation happens. Having said that, we also take into account the fact whether changes and events relate purely to the niche area of innovation or the narrower context (regime) of the innovation or its wider context (landscape). This approach is taken from work on the multi-level dynamics of the regime transformation (Geels and Schot 2007) and it refers to the range of an occurrence.

Categories that capture ‘event’ types, i.e., what happened in the course of innovation work, are the following:

- On the one hand, plans are made (‘planning’), and, on the other hand, options and alternatives are explored (‘exploring’), how the plans can be concretised or implemented, or which plans are sensible and desired at all. ‘Exploring’ refers to the acquisition of useful knowledge about people and regions as a basis for further activities and building relationships.

- We differentiate between types of stakeholder interactions. ‘Infrastructuring’ refers to a platform and network building action, such as efforts for setting up an innovation platform and networks, targeted events and regular meetings, training opportunities and the like. The focus is on (a) stabilising/destabilising the network of stakeholders, for instance, through a meeting; or (b) consolidating or changing, developing and extending, or shrinking the stakeholder circle; also inviting a moderator for a workshop. In the case of the Eisenwurzen, for example, this became the core idea for the innovation of ecosystem governance in the region: to build an infrastructure for further collaborative innovation in more targeted, product-specific respects. In other cases, this was an accompanying topic that was supposed to open up an arena for negotiation and development to more specific innovations.

- Internally ‘collaborating’ in contrast to ‘infrastructuring’ is about working together, when, for example, regional teams and stakeholders take action together and do something together that goes beyond the normal process the core team carries out with the stakeholders.

- The categories ‘docking’ / ‘undocking’ refer to external efforts to hook up with content-related intentions, for example, in Eisenwurzen a group of actors (some from outside the project) used the project framework and the impressive list of participants as an opportunity to present a new pyrolysis technique, which could possibly have become another prototype for the project, and to test it out with the participants (docking). Ultimately, this did not result in a new initiative in the project itself (undocking).

- With respect to scenarios used in the innovation process as a means to pinpoint specific innovation options, we used the categories ‘forking’ / ‘coupling’. Forking, on the one hand, means the development of two or more ideas for scenarios out of one more general idea. The conjoining of scenario ideas, on the other hand, is a case of coupling. Both apply in most cases to IR team / InnoForESt project internal integration or differentiation of scenarios, but can also be the result of a workshop and stakeholders’ decisions on what to further pursue.

- A wide variety of internal and external signals and events that appear inevitable we call ‘impulses’, because they are not simply negatively connoted shock events (cf. Van de Ven et al. 1999; Geels and Schot 2007). These could, e.g., be a group discussion during a workshop with a significant effect on the further innovation work. Impulses can also be rather critical events like new insights, push, shock, crisis, rather incremental or radical – for instance, the bark beetle crisis in some regions, the forest fires in Sweden, or the Vaia storm causing damage in the Trentino and Eisenwurzen regions.

- By contrast, with ‘shift’ we indicate that something is moved to another level or area, be it actor roles, participating personnel, criteria for taking decisions, or problem perceptions or framings, aims and objectives. This is not a question of maturation per se, but of the perceived and conveyed interpretation of a problem around which the innovation work revolves.

When we look at the journeys, we collect various “moments” in which something decisive happens in order to peel out the cornerstones of the overall context. If we were to discuss individual actions or measures, we could call them actions. But we do not. Looking back, we observe that a special moment of cooperation has arisen; that forking or docking took place; etc. What exactly is behind it as an action, we cannot consider or “resolve” in so much detail. Therefore, we use the term ‘events’.

Categories for process changes are the following:

- A ‘setback’ is a step backwards or difficult obstacles that cannot be bridged on the innovation development path. What has already been achieved is questioned or lost, for example, a mistake that does not immediately lead to constructive impulses for continuation, a stagnation when that halts the innovation development flow or a deadlock when the innovation efforts come to a temporary standstill. This is about at least difficult obstacles that cannot be bridged (for now). This category is further used to describe their effect. Consequences of strong setbacks degrade the level of maturation. The analysis records a setback when it can be observed that it is not about the permanent end of an effort or a scenario or a course of action.

- ‘Termination’ addresses the permanent end of an effort, an innovation option or a sub-process, or actors leaving or a scenario/theme ending (cf. Stegmaier et al. 2014).

- ‘Convergence’ means the approximation or alignment of something within the innovation project and something from outside, such as elements of innovation entering the general policy in a sector or vice versa that what generally happens fits well with activities in the innovation project. An example is the state forestry policy in Trentino, which was pursued far after the start of the project. The policy relies on participative forms that fit well to the interaction with stakeholders in the project. Thereby the project suddenly acts as a pilot for major politics. Convergence also includes the fusion of the innovation with something that already exists outside of the project.

- ‘External relations’ refers to eventually or occasionally taking action together with external actors, such as entertaining close links to interest groups, a research institution, or potential but not (yet or anymore) participating stakeholders without direct and formal project participation.

- ‘Tensions’ address disagreement with internal or external actors about the knowledge or value basis, or political and/or economic aims or interests. The category refers to the occurrence of tensions with internal or external actors – for example, when criticism comes from outside an innovation project, but with a certain impact on the project, i.e., a political party or NGO that speaks out against the compensation strategy pursued in the project.

The above defined ‘event’ and ‘process changes’ categories do not imply a judgement about the maturation of an innovation idea or a prototype. The question of changes in maturation levels is an empirical one and thus answered for each incidence in the individual cases. A tension, setback or termination does not have to be bad per se for the progress of the innovation efforts, neither a convergence or external relation only positive, but can sharpen the focus, give new impulses, trigger clarifications, or pool forces.

In addition, there are analytical categories that characterize the event in terms of the direction and scope in which the innovation comes into play. We introduce two categories that do not describe individual events, mechanisms or activities, but serve to mark the context of the innovation. The first indicates the degree of maturity an innovation has reached – this happens in purely qualitative and relative terms, without numerical ranking, while the second group refers to the multilevel consideration according to Geels and Schot (2007):

- With ‘maturation’ we depict the degree of an innovation development in qualitative terms, as a step up to more and a step down to less matured innovation ideas, or remaining on the same level when either of both is the case. This is a judgement we make for each event or activity in the context of the innovation process. It will be clear from the narratives in the individual innovation journey sections below (see 5.1).

- We refer to the context of the ‘regime’, when a niche process or an event interacts with the incumbent regime development (e.g., the wood price drop in Trentino after the Vaia storm, or the new compensation regulation in Finland which was pending for quite a while and thus, some private sector stakeholders tended to wait before engaging more). ‘Regime’ stands for the immediate (endogenous) context to which the innovation relates to. In relation to the ‘regime’, innovation is to be understood as a niche process. This enables events to be shown in conjunction with the development of the established regime.

- When a niche process or event interacts with the broader landscape development, we refer to the context of ‘landscape’. Landscape stands for other indirect circumstances (exogenous context). In these contexts, we have found that events etc. such as impulses or setbacks can also occur. In relation to innovation as a niche process and ‘regime’, ‘landscape’ refers to events and trends in a broader context, such as climate change and related policies, framework laws at EU level.

Finally, we differentiate phases of innovation development that are important in the analysis of innovation processes. We use the term ‘origins’ (cf. Voss 2007) to capture the pre-history of an innovation effort in a region prior to the preparation and formal start of the project. ‘Origins’ are the earlier innovation efforts, policy initiatives, legal changes, or bio-physical developments that precede the actual project. During the phases, all kinds of activities and events can occur. ‘Gestation’ (cf. Van de Ven et al. 1999), by contrast, addresses the initiation period of the new innovation effort: the more tentative initial efforts undertaken during the preparation phase until the formal start and first period of actual project work: explorations with stakeholders, analyses assessing the situation and scanning of the horizon.

In the analyses of our regional cases, we noticed that the ecosystem services governance innovations sometimes look back on a long tradition and early attempts to start again, and that some existing formats already have an extensive history. In these situations, the history of the innovation needs to be well understood to be able to assess existing continuities and discontinuities. This includes pathways that may (need to) be continued or interrupted, and actor constellations that have to be critically assessed beforehand, when something is no longer functioning well, or where successful cooperation requires future oriented adjustments. In addition, InnoForESt was often not the only research or EU project initiative that ran in a region. Therefore, it is important to review this to be able to learn lessons from available knowledge or at least not to make mistakes again. The fact that InnoForESt as a EU Horizon 2020 Innovation Action started, does not imply that ongoing forms of service change automatically or that stagnant or non-existent potential suddenly opens up. Thus, a close look at what happened before the innovation work in the project context started is needed to understand the development of the innovation process.

5 Empirical Innovation Journeys

With the categories of the above adapted innovation journey framework we analysed each of our six regional innovation processes. In the following, we present the results of applying our innovation processes analysis categories to each Innovation Region in a coherent narrative. The pivotal points – i.e., the main results and structural changes in the innovation process and the stakeholder networks involved are furthermore visualized in a comprehensive process and network figure for each innovation journey.

Both the narrative and graphical representation of the innovation processes must subsequently compress and stretch the strictly taken time. If something happens, it is discussed and shown, if nothing happens, it is not. The x-axis is therefore not the time, but the sequence of events that are important for innovation work. If more happens in a workshop than over the months between the workshops, then the density of events is also zoomed in. This makes it clear that the workshops are in many cases decisive moments in the negotiation between the stakeholders.

5.1 Eisenwurzen Forest-Wood value network, Styria/Lower Austria/Upper Austria, Austria

Origins

In Eisenwurzen, efforts towards a sustainable regional development with emphasis on stakeholder participation, nature conservation, and value creation go back to the 1990s. In 2004, a Long-Term Social-Ecological Research platform Eisenwurzen (LTSER) was established with the Study Group for International Analysis (STUDIA) as coordinator for the Upper Austrian region. This LTSER platform is a network of research institutes, national parks (NP), and other organisations that has already hosted a range of research projects, including on nature conservation and sustainable ecosystem management (impulse, infrastructuring, regime ↑). Between 2011 and 2013, an EU-funded INTERREG project “Modular furniture from National park regions” and international art and design colleges, also coordinated by STUDIA, explored the connection of regional joinery handicraft and contemporary design in Eisenwurzen. Despite these efforts, however, the stakeholder network along the forest-wood value chain in the region remained rather fragmented before the start of InnoForESt (infrastructuring, regime). At that time, innovation primarily depended on individual action. Furthermore, activities started in the INTERREG project petered out after the project ended. In particular, regional stakeholders like joineries did not feel sufficiently integrated in the project and appeared somewhat discouraged and reluctant to engage in similar project-related activities again. However, the network established during the INTERREG project has arguably remained intact regardless, albeit dormant (setback ↓).

Gestation

During the preparation of the proposal for InnoForESt, one scientist who became part of the Innovation Region Team on behalf of the University of Innsbruck (UIBK), Christian Schleyer, was affiliated with the Institute for Social Ecology (SEC) – a founding member of the LTSER platform Eisenwurzen and host of the LTER Austria. The institute’s contacts were used to reach out to the then scientific coordinator of the LTSER platform, Andrea Stocker-Kiss (Environment Agency Austria), when exploring options for an Austrian Innovation Region. Consequently, STUDIA was invited to participate in InnoForESt as a practice partner due to their good connections to both practitioners (e.g., through the INTERREG project) and scientists (e.g., LTSER platform) in the region (infrastructuring, impulse). As STUDIA had been involved in and coordinated the INTERREG project on Modular Furniture, joined InnoForESt, initially seeing the project as an opportunity to reinvigorate that idea (planning ↑). Further, the InnoForESt network was enriched by inviting actors from the LTSER platform to become affiliated partners. This included the LTSER platform’s scientific coordinator, Ms. Stocker-Kiss (LTSER), and Mr. Wölger (NP Gesäuse) acting as two of the InnoForESt platform’s key nature-conservation related partners (forking).

Project progression

Conducting a stakeholder and governance system analysis

When InnoForESt started , the general aims of the project team were to bring out stakeholders’ already existing but often hidden innovation activities and ideas and to promote those to enable bottom-up innovation (planning). In particular, since there was only little information on how the results of the INTERREG project had been perceived by the regional stakeholder, it was unclear at first, whether pursuing the modular furniture idea was at all promising and whether stakeholders, who had previously participated in the INTERREG project, would be willing to engage in this matter once again. This potential – or at least anticipated – reluctance on part of stakeholders in the region also informed STUDIA’s initial cautiousness about InnoForESt’s chances. To resolve this, remove some of the uncertainties, and explore ‘alternative’ ideas, the scientific partner UIBK conducted a comprehensive stakeholder analysis in the first half of 2018 to learn about the regional actors interests, visions, and concerns (exploring, infrastructuring). In these interviews, but also in further bilateral talks, both scientific and practice partners engaged with stakeholders to (a) introduce the stakeholders to the project aims, potential benefits, and applied methods, (b) establish a spirit of Eisenwurzen as an Innovation Region, and (c) explore who else could contribute to the innovation process. Additionally, the interviews established contacts and fostered stakeholder commitment to participate in the upcoming InnoForESt-related events (exploring, infrastructuring, impulse ↑) (see D5.1, 5.2). Overall, this led to a better understanding of stakeholders’ expectations and ideas, for example, fostering forest education, and involved stakeholders in the innovation process right from the start. Insights gained from the stakeholder analysis informed the IR team’s decision to pursue several – instead of only one – forest-related governance innovation ideas in parallel; at least for the time being and only as long as a sufficient number of stakeholders showed interest. This decision represented an evolution of the initial project idea (shift). Instead of immediately committing to one innovation idea, such as modular furniture, the IR team opened up to allow for even more new ideas and input from the stakeholders. As a result, three first main innovation ideas (furniture and design, mobile wooden (tiny) houses, and tours to experience the forest) emerged early on (planning, forking).

Focus groups and InnoForESt General Assembly in Trentino

In October 2018, a set of three focus groups (see D4.2) – one per innovation idea – brought together the mostly different stakeholder groups (infrastructuring ↑). This was an essential probing of the three previously collected ideas which were sufficiently interesting to the stakeholders and prepared both the project team and the stakeholders for the CINA workshops. During each of the focus groups (INNO-1, INNO-2, INNO-3), participants elaborated on various aspects of the respective innovation idea, such as potential results/outcomes/effects or obstacles, but also identified other stakeholders/organisations that would need to be included in further activities (exploring).

In October 2018, the first annual InnoForESt General Assembly meeting took place in Trento, Italy. At this meeting, amongst others a focus was put on presenting the outcomes of the Governance Situation Analysis, the Stakeholder Analysis and the discussion of scenario drafts among all InnoForESt project partners (exploring).

The first CINA workshop – Introducing the three innovation ideas

Based on the outcomes of the three focus groups, the IR team started the preparation of the first CINA workshop. Apart from deciding to continue to feature all three innovation ideas, in particular STUDIA followed up on the list of stakeholders to be encouraged to join the CINA workshop by calling more than 60 regional stakeholders and inviting them to the workshop, but also approaching (non-regional) experts who could provide some input (exploring, infrastructuring, planning).

The first CINA (1.1) workshop, which took place in February 2019, brought together a broader range of regional, but also non-regional stakeholders (see D4.2). This was partly due to the extensive communication efforts on part of STUDIA including not only personal phone calls but also the public announcement of the workshop in regional newspapers and other media outlets. In the first part of the workshop, for each of the three innovation ideas (1. Furniture, design and region (INNO-1), 2. Mobile wooden houses & tourism (INNO-2), 3. Experiencing forest and wood (INNO-3), one member of the project team and one regional stakeholder gave input presentations (exploring).

In the second part of the workshop that featured some extensive group work, for each innovation idea it was explored what each individual stakeholder could contribute, what interested him/her with respect to the innovation idea, what specific opportunities and obstacles were, and how the idea could be promoted. The engaged discussions of all three innovation ideas showed that most stakeholders were keen on connecting and pursuing two or more of those ideas (exploring ↑).

Triggered by the plenary discussion on the innovation ideas, but also by an impulse presentation by Veronika Müller on the wood design training course “Überholz” at the University of Art and Design Linz and the successfully established wood-related stakeholder platform ‘Werkraum Bregenzer Wald’ in Vorarlberg (Austria), workshop participants reiterated the importance of platform and network building (external relations). This was perceived as even more important since stakeholders expressed the wish to create synergies between different separated innovative activities and to strengthen relations within the region but also to increase visibility and to motivate other stakeholders to join the network and to get public funding (infrastructuring, impulse).

Until the second CINA (1.2) workshop in May 2019, many activities were undertaken by the IR team, such as smaller-scale meetings with regional stakeholders but also analysing and discussing the results of the first CINA workshop, to keep the innovation process running and to plan the workshop (exploring, planning). Legal issues for implementing tiny houses continued to appear unsolved. Regional tourism associations as an important partner for a planned pilot realisation began an internal reorganization process and therefore stopped their involvement, which provoked one of the major protagonists for tiny houses (SPES) to pull out from platform activities (setback).

As a result of the continued high interest in all innovation ideas, the IR team decided that all of them should be pursued further and that the idea of establishing an innovation platform forest-wood should be picked up as well as an organisational construct that could, among others, allow for integrating the three already existing innovation ideas as well as enabling and facilitating stakeholder exchange in general. This innovation platform was conceptualised and introduced as a fourth, complementary innovation idea (shift, forking ↑).

The second CINA workshop – Introducing the fourth innovation idea

This second CINA (1.2) workshop took place in a different location, the neighboring Enns valley, to better reach potential stakeholders (especially forest related small-medium enterprises) from the province of Styria (see D4.2). In general, it proved to be difficult during the workshop to account for the high number of stakeholders who did not attend the first CINA workshop, which was to a large extent caused by the change in location. While the new ones needed to be ‘filled in’ with respect to previous discussions, ‘old’ stakeholders perceived this as being too repetitive (setback ↓). The workshop started with an external input from Gabriel Gruber presenting the wood-related innovation success story of the work group ARGE s’Hoiz (“Working group wood”) as an illustrative example of an organised stakeholder network/platform (external relations, impulse). The following parts of the workshop were structured in a way that was intended to activate stakeholders – partly working in smaller thematic groups – and create a sense of ownership for one or more of the innovation ideas. To that end, the stakeholders had to present the results of respective group work themselves (exploring, infrastructuring).

Contentwise, the necessary steps towards implementation of the three existing innovation ideas plus the added fourth idea on the innovation platform forest-wood were discussed. With regard to these innovation ideas, the stakeholders expressed concerns that bureaucratic and administrative obstacles will hamper their implementation. Some stakeholders questioned the economic viability and competitiveness of a focus on regional wood (setback). Further, actors from the forestry sector pointed out that so far they did not feel the innovation ideas were connected to their interests and that forest owners were not sufficiently represented in the workshops (setback ↓). Concerning the establishment of a platform, it turned out that some stakeholders first wanted to decide on which concrete innovation idea to pursue further before they felt able to decide on the organizational form of the platform. On a more general level, in comparison to the first, rather enthusiastic CINA workshop, the stakeholders expressed more skepticism about the continuity and sustainability of the project as such and raised fundamental questions regarding the actual goal of InnoForESt, the role of InnoForESt in the region, how the self-organization of stakeholders should work, and especially the continuity of the innovation ideas after the end of InnoForESt (setback). Adding to this, the establishment of a digital platform which was very broadly introduced as an idea during the workshop did not attract much interest among stakeholders.

The first Task Force meeting, InnoForESt-supported workshop, and planning an excursion

Following the second CINA workshop and the rather limited progress regarding the individual innovation ideas, the IR team decided to look for ‘champions’ of strongly motivated and committed stakeholders for – ideally – all three thematic ideas, so that further work on the individual innovation ideas could be organised in smaller groups and would become more (regional) stakeholder-driven with fixed responsibilities among stakeholders. To identify those ‘champions’ and to discuss the overall strategy of further developing the innovation platform, the IR team approached potential ‘key’ stakeholders and invited them to join a task force meeting (planning).

Some weeks before the task force meeting, Josef Lumplecker (LUMACON Holztechnologie GmbH), who took part in the second CINA workshop, initiated an InnoForESt-supported workshop (June 2019) as a small satellite event where a concept of a business park was presented and discussed with local forest owners, forestry companies, and employees of the municipality of Weyer, and representatives from the LEADER region (docking). The park’s operative purpose is beech wood processing for construction in combination with pyrolysis of residues (for energetic use), and thus tackles a major unused forestry potential of the region Eisenwurzen. The initiative was developed outside InnoForESt, but needed InnoForESt as a neutral platform to gain further confidence in the region and among business partners. As this project relied on investments of private forest owners and public co-financing, the idea is further pursued by these partners.

At the task force meeting that took place in July 2019, purpose, objectives, and principles of the innovation platform (INNO-4) were discussed including the option to develop a ‘Memorandum of Understanding’ for all interested regional stakeholders to sign at the next CINA workshop and beyond (see D4.2). Further, the idea of organising an excursion to Vorarlberg to visit, among others, the successful wood-related platform ‘Werkraum Bregenzer Wald’ and to learn from this ‘best-practice’-example was very welcomed (impulse, infrastructuring, exploring). In contrast, the first rough mock-up of the regional InnoForESt digital platform was presented, yet – in this form and without progress on developing the physical platform – not perceived as an essential keystone for establishing the stakeholder network (setback).

While the task force meeting had essentially failed to identify ‘champions’ for any of the three thematic innovation ideas and to initiate substantial progress here (setback). Further, the discussions during the meeting introduced ‘beech wood’ as ‘topic’ that seemed to be relevant for all three thematic innovation ideas and which could have some integrating function (exploring ↑).

As an outcome from the task force meeting, activities planning the excursion to Vorarlberg in early autumn 2019 intensified (planning), yet due to a lack of substantive interest it was first postponed and later merged with an initiative by MHC, planning to visit the same sites in Vorarlberg (docking). As a second outcome of the discussions, exploring options of an appropriate organizational form of the innovation platform were initiated (planning).

In September 2019, a SETFIS interview with members of the scientific team took place. It had no discernible effect on the innovation’s development.

The InnoForESt General Assembly in Schlierbach: Market place and excursion

On the occasion of the InnoForESt-Consortium Assembly (October 2019) in Schlierbach, a ‘market place’ was organised as a side event. Here, regional stakeholders were invited to learn from the other IRs in InnoForESt and exchange with the respective IR teams. This event was complemented by an excursion ‘Forest-wood-value-chain Eisenwurzen’ the following day where InnoForESt members were given insights into the forest-wood value chain of the Eisenwurzen region and some of the regional stakeholders had the opportunity to communicate innovative approaches to and to exchange experiences with an international community (external relations, impulse, exploring, infrastructuring ↑). Both events triggered the regional stakeholders’ awareness of the importance of getting organised in the form of a stakeholder platform/network and the positive feedback from the other IR teams encouraged the participating regional stakeholders to continue along this path.

In November 2019, a SETFIS interview with the leader of the practice team took place. It had no noticeable effects on the development of this innovation, but was very helpful for the overall project in order to keep an overview of the regional developments.

The third CINA workshop

At the third CINA (2.1) workshop (January 2020), the main focus relied explicitly on the platform development and on discussing options of – and thus further developing – the organizational form of the innovation platform to ensure their sustainability/permanence after the end of InnoForESt (shift) (see D4.2). Further, Gabriel Gruber once more presented the work group ARGE s’Hoiz as best practice example, focussing here on organisational features (external relations, infrastructuring, impulse).

Based on fact sheets on three organizational forms (ARGE-work group, Association, and Cooperative) that had been prepared by the IR team beforehand, benefits and disadvantages of different organizational forms were elaborated discussed in detail with respect to pros and cons as well as fit to the needs of the ‘Innovation Platform Forests-Wood’ during some group work at the workshop (exploring). Although interesting and engaged discussions – somewhat hampered, though, by the fact that 25 students from a regional (Raumberg-Gumpenstein in the Styrian part of the Eisenwurzen) forestry related vocational training class had joined the workshop who were otherwise not directly involved in the innovation process (external relations) – there was no clear preference among the stakeholders, although a work group seemed – for the time being – the most cherished idea. It still remained unclear who of the stakeholders would take responsibility in any of these organisation forms. When the question was addressed, stakeholders reacted reserved, possibly because they could not yet agree upon a goal of the platform (setback).

The third CINA workshop highlighted that there is a strong need to create a common vision and a concrete goal among the stakeholders to ensure a continuation of the innovation platform development and related activities after the end of InnoForESt. Thus, the IR team planned to organize a second task force meeting in March 2020 to decide on a joint vision/set of objectives, but also to hand over responsibility to the stakeholders (planning).

A rescheduled Task Force meeting and outlook

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, emerging in early March 2020, first, the planned task force meeting had to be postponed until June 2020. Second, between March and June 2020, it was also difficult to keep up contact with the stakeholders and the possibilities for exchange were restricted because of the reduced capacities of the IR team and most regional stakeholders during this phase of the pandemic (setback/L ↓). This is particularly problematic as the last nine months of InnoForESt were supposed to be used to hand over responsibilities for furthering the innovation process to the regional stakeholders.

For the second task force meeting (June 2020) (see D4.2), which was carried out as a hybrid event with some of the stakeholders meeting in Schlierbach, and other stakeholders and members of the IR team joining via Zoom, the IR team had compiled and clustered the main statements related to common objectives made by stakeholders during all previous meetings and smaller-scale discussions. During the task force meeting, which also functioned as a road mapping CINA-Type-3 workshop, the main objectives and the clustered subordinate objectives were discussed, detailed, modified and complemented by all participants (infrastructuring, exploring). While there was some form of consensus with respect to the more general objectives (creating appreciation of wood from the region for the region; linking innovation, ecosystem services and region), there remained a greater variety of opinions and preferences with regard to the sub-goals and their operationalisation among the participants. Compared to the first task force meeting, a smaller number of participants joined the – Covid-19 induced – hybrid-virtual format (setback/L). Eventually, however, no individual or groups of stakeholder(s) stepped forward proactively taking the lead in continuing organizing further meetings of the platform or the (further) development of the platform in general beyond the end of InnoForESt in December 2020 (termination ↓). One effect of the platform activities relates to the planned construction of bus shelters made of local wood from the Almtal region. Some participants from this subregion of the Eisenwurzen, who were involved in most of the workshops and activities, decided to leave the platform and continue to develop projects independently from the InnoForESt platform (termination). Due to ongoing Covid-19 restrictions, another final meeting of the InnoForESt platform is very unlikely. However, the regional management and two LEADER Local Action Groups (Nationalpark Region Oberösterreichische Kalkalpen, Traunviertler Alpenvorland), who have been involved in the InnoForESt platform from the beginning, stated that the promotion of the value chain forest/wood is expected to stay on the regional agenda.

In retrospect, one can see the innovation journey of the Eisenwurzen Forest-Wood value network characterized by a strong, intensive start and main part, as well as a comparatively less progressive late phase mainly due to the reluctance of stakeholders to take the further operation of the platform into their own hands, and on top of that the difficulty of meeting under Covid-19 conditions.

No concrete further activities have been planned. There is still the idea to find post-Covid-19 an opportunity for the scientific team to present the results of InnoForESt, including those from other Innovation Regions.

5.2 Habitat Bank of Finland, Helsinki, Finland

Origins

The idea of using economic instruments for steering biodiversity compensation had already arrived in Finnish forest governance years before InnoForESt launched: from 2002 onward, a national scheme called “METSO” provided Finnish landowners with monetary payments for voluntarily implementing biodiversity conservation measures in forest areas, which would then be protected either temporarily or even forever. This also included the idea of compensating for lost biodiversity values, paid by those who cause the loss. METSO laid the groundwork for stakeholders’ general acceptance of the idea of receiving monetary payments for conserving biodiversity in their forests (impulse ↑). The stakeholder networks already in place because of METSO were fertile ground for SYKE, the Finish Environmental Institute and later science partner of InnoForESt, to show the idea of the Habitat Bank of Finland, which is envisioned as a market mechanism for the conservation of biodiversity (infrastructuring).

In 2015, SYKE and University of Helsinki enrolled the idea of Habitat Bank of Finland ecological compensation in a research impact competition called the “Helsinki Challenge”. Later also the University of Jyväskylä joined, along with several stakeholders. Their idea “Biodiversity Now!” succeeded in obtaining seed funding, which initiated the collaboration (collaborating ↑). At that time, the idea of ecological compensation had also gained momentum due to EU stimuli such as the habitat restoration target or the No Net Loss policy (impulse). Through “Business and Biodiversity” trainings, SYKE and a Finnish organization promoting sustainable business (FIBS) also sensitized private companies for the topic by suggesting options to realize corporate social responsibility activities (infrastructuring).

SYKE intensified its work on a voluntary biodiversity compensation scheme and acquired funds for developing the Habitat Bank of Finland concept in an at the time of writing ongoing project called “EKOTEKO”, which is devoted to developing a calculation method for the ecological value of areas with deteriorated biodiversity and potential compensation sites that will make these sites comparable (planning). EKOTEKO, which is led by the University of Helsinki, and what would become InnoForESt, which is led by SYKE, are meant to cross-fertilize each other (docking). The aim was to test the feasibility of ecological compensation and to develop a pilot project that should promote cooperation between business and administration.

The emergence of the Habitat Bank of Finland occurred in a broader context of a discussion on biodiversity offsetting. In this discussion, the concept of “ecosystem services” with all its facets remained relatively less important. From 2016 onwards, ecological compensation climbed up the political agenda: the Ministry of the Environment commissioned and funded studies on biodiversity offsetting (external relations, impulse ↑). They picked up offset payments as a way to involve private actors in ecological compensation schemes.

Gestation

The InnoForESt proposal was closely linked to existing ideas about the Habitat Bank of Finland and the EKOTEKO project. The Habitat Bank of Finland was introduced in InnoForESt as an innovation idea of organising private sector habitat banking to compensate for the ecological harm its activities cause. From the start, there was no specific limitation to the kind of activities or businesses to be included, as long as they were eligible for compensation.

The Finnish IR team members complemented each other well in terms of scientific and practitioner background. Due to previous collaborations, the science partner SYKE and the practice partner Finish Forest Centre (FFC) were well-positioned for the work on the Habitat Bank of Finland. This included the activation of the relevant forest stakeholder networks and the awareness of stakeholders’ interests (infrastructuring, exploring). The work of the IR team, therefore, did not need to concentrate on building new networks, but on operationalising and piloting the Habitat Bank of Finland (planning). An important step was to link supply and demand of ecological compensations, bringing together companies intent on collaborating with forest owners.

Project progression

Laying the groundwork

In the first six months of 2018, the main focus of numerous meetings organized by the IR team was to create a shared vision and knowledge base among the key stakeholders, including forest-owners (Central Union of Agricultural Producers and Forest Owners), the Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment of Central Finland and representatives of the city of Jyväskylä (infrastructuring, exploring). In particular, the IR team’s strategy was to meet with each stakeholder or organisation individually to create an atmosphere in which the stakeholders could freely express their thoughts and requirements. The general attitude towards innovation was positive at those meetings, but it quickly became clear that two preconditions were considered necessary for the implementation of the pilot project. First, a kind of intermediary or broker would be required to manage the remuneration agencies and finances. Second, the exact compensation criteria and mechanism needed detailed elaboration to convince companies to commit. This led to three rough scenarios for those mechanisms: an authority-driven mechanism, a voluntary contract scheme, and a nature value bank (planning, forking). Among others, these rough scenarios were based on a stakeholder analysis and governance situation assessment undertaken as an InnoForESt activity (exploring).

First CINA workshop and landmark decisions