Deliverable 6.3: Set of policy recommendations for EU wide governance strategy for sustainable forest ecosystem service provisioning and financing

| Work package | WP 6 Policy and business recommendations and dissemination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deliverable nature | Report | |||

| Dissemination level (Confidentiality) | Public | |||

| Estimated indicated person-months | 9.5 PM (Carolin Maier, WP6-FVA)

3 PM (Lena Holzapfel, WP6-FVA, Student assistant) 2 PM (Wiebke Hebermehl, WP6-FVA, Student assistant) (2.5 PM Carol Grossmann, FVA own contribution) 0,25 PM per practitioner and scientist from all IR and WP |

|||

| Date of delivery after first extension | Contractual | 31.07.2019 | Actual | 31.07.2020 |

| Date of delivery after second extension | Contractual | 31.12.2020 | Actual | 18.12.2020 |

| Version | 0.0 | |||

| Total number of pages | 84 | |||

| Keywords | FES provision, policy recommendations, options for action, Innovation Regions, forest owners and managers, entrepreneur, NGO, policy-maker, scientist, transdisciplinary research | |||

Executive summary

Global environmental problems, increasing urbanisation, industrialisation pressures, and market dynamics among others, hamper the balanced provision of the full range of forest ecosystem services (FES). At the same time, societal demand, particularly for regulating and cultural FES is increasing. Yet thus far, forest owners are usually unable to generate revenues off the broad range of ecosystem services their forests provide, forcing them to base management decisions on marketable goods, mainly on timber production. Between 2017 and 2020 InnoForESt has worked with and in six local level initiatives across Europe to analyze and (further) develop innovative governance mechanisms for securing FES provision and financing. The governance innovations in focus can largely be grouped into network-centered and payment mechanism-centered approaches.

This report draws on project findings regarding stakeholder network development, governance innovation development for FES-related income opportunities, and payment mechanisms for FES provision and financing to present targeted recommendations to the following actors:

- Forest owners and managers (chapter 2.1)

- Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) & associations (chapter 2.2)

- Non-sectoral Entrepreneurs (chapter 2.3)

- Local-level policy-makers (chapter 2.4)

- National & EU level policy-makers (chapter 2.5)

- Scientist and future research funding (chapter 2.6)

In addition to actor-oriented recommendations, the following overarching conclusions have emerged:

- Governance mechanisms (potential) impacts on forest management, FES provision, and forest-based income can vary considerably. These are three distinct elements and not necessarily mutually reinforcing.

- Payment mechanisms financing the provision of FES require a clear denomination of the (different) FES addressed, clearly defined FES related objectives and context specific solutions.

- Securing FES provision and financing hinges on public policy and support which can be integrated into public policies and initiatives that already exist in the fields of rural economic development, climate change resilience, and biodiversity protection and should be addressed more explicitly in new and emerging related policy strategies.

- Currently policy demand for FES provision is largely reactive to shortage. Needed is a turn towards proactive policy formulation. A number of ongoing related policy initiatives may offer windows of opportunity to pro-actively foster the future provision of FES, in particular regulating and cultural FES, others may reduce their future availability. FES assessment and monitoring systems should be prerequisites for respective public support and should include data on ecologic forest conditions, societal demand for FES, as well as information on the institutional setting and economic revenue streams.

- The biggest political potential for advancing means for the sustainable provision of FES lies in the further development and implementation of the ‘Green Deal’ and the EU Forestry Strategy provided the structural change actively integrates the important role of multifunctional sustainable forest management.

- While FES-related innovation systems are inherently a context-bound social-ecological-technical issue, a certain level of homogenisation of national FES-supportive regulation and legislation within the European Union is expected to enhance FES provision and financing.

- Building diverse stakeholder networks is important for local level governance innovation development. Forest owners and managers play a key role in these networks.

- Findings indicate that the potential of private market based innovative governance mechanisms is limited to complementing policy led and public efforts to secure FES provision and financing.

List of tables

- Table 1: Overview Innovation Regions

- Table 2: Validation of the most influencing factors by IRs’ representatives

- Table 3: Overarching themes and targeted actor groups

- Table 4: Overview Innovation Regions

List of figures

- Figure 1: Pre-recommendations-workshop survey – questions directed at InnoForESt scientists

- Figure 2: Pre-recommendations workshop survey – questions directed at InnoForESt IR practitioners

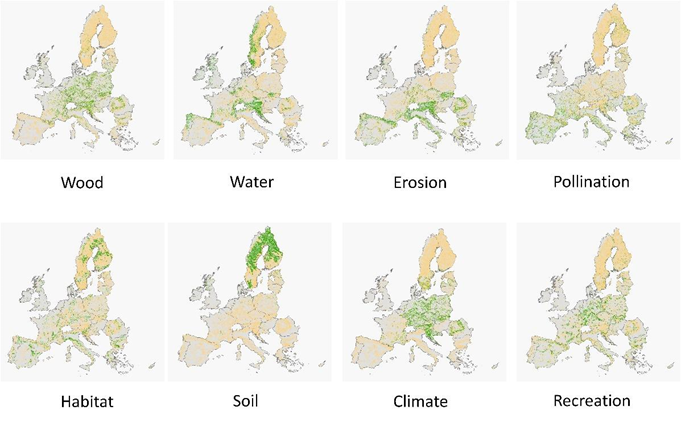

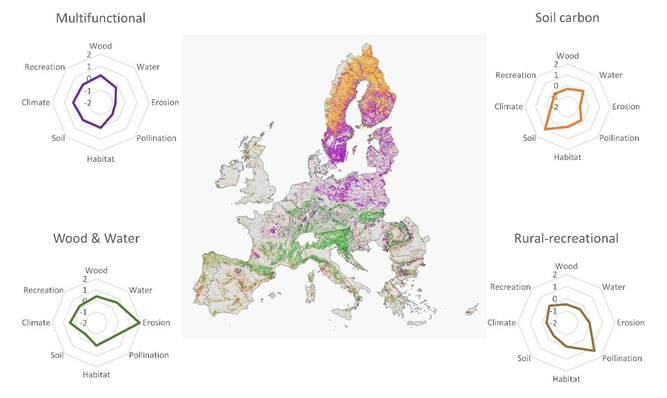

- Figure 3: Biophysical and Institutional Mapping

- Figure 4: The InnoForESt Approach

- Figure 5: The InnoForESt multi-actor-approach

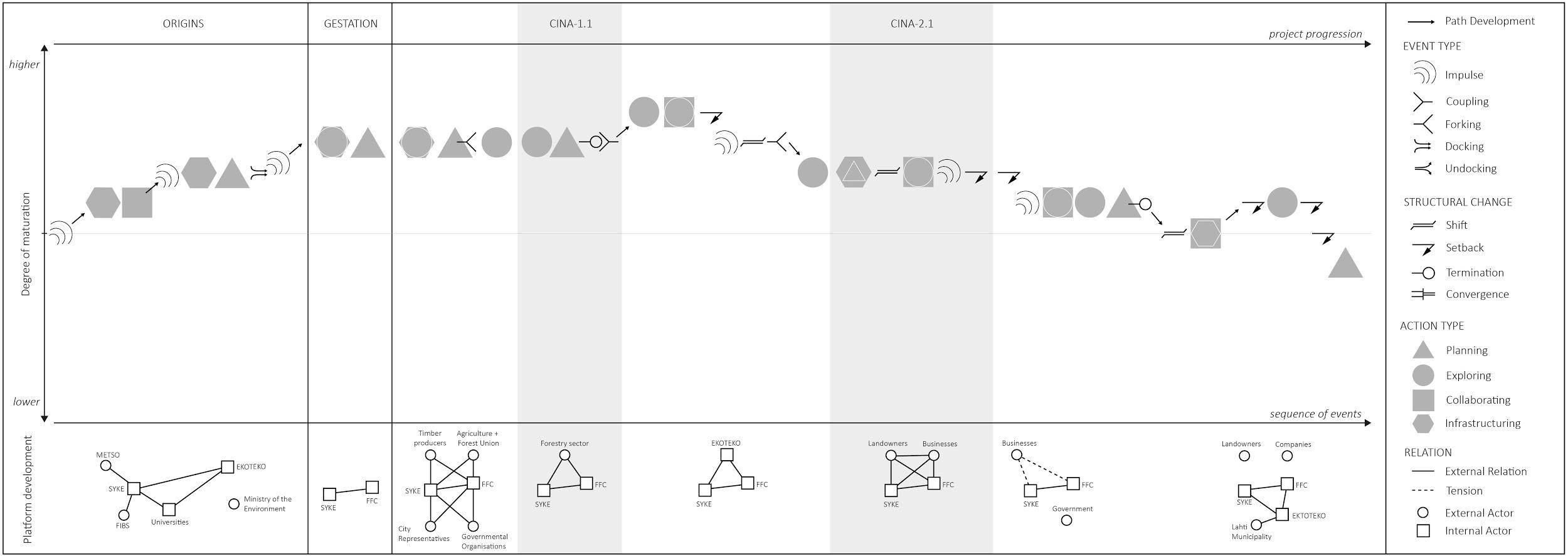

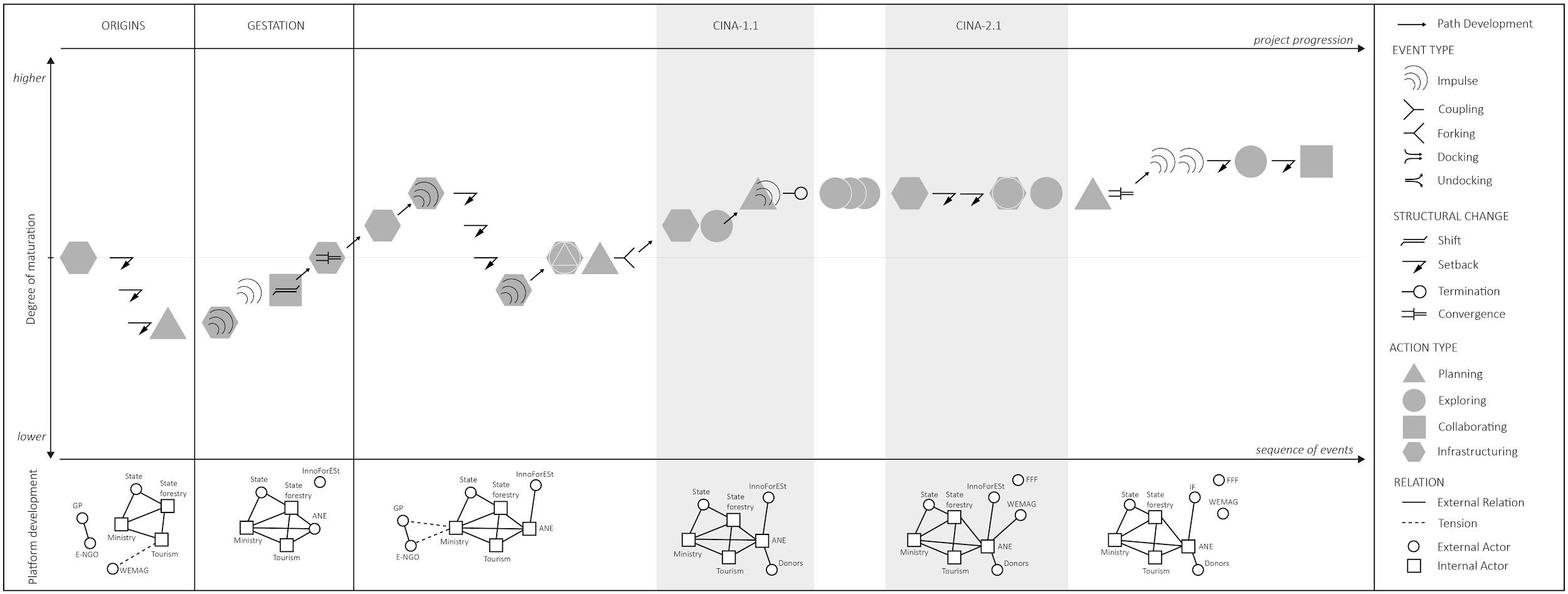

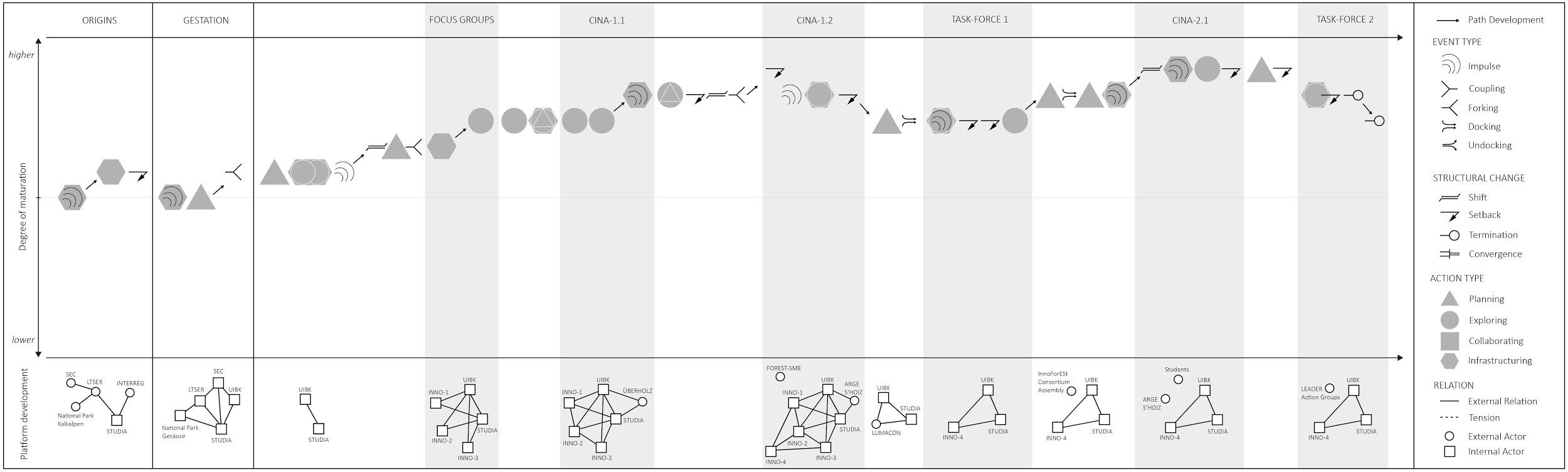

- Figure 6: Innovation Journeys

- Figure 7: Cross case analyses on key factors influencing governance innovations

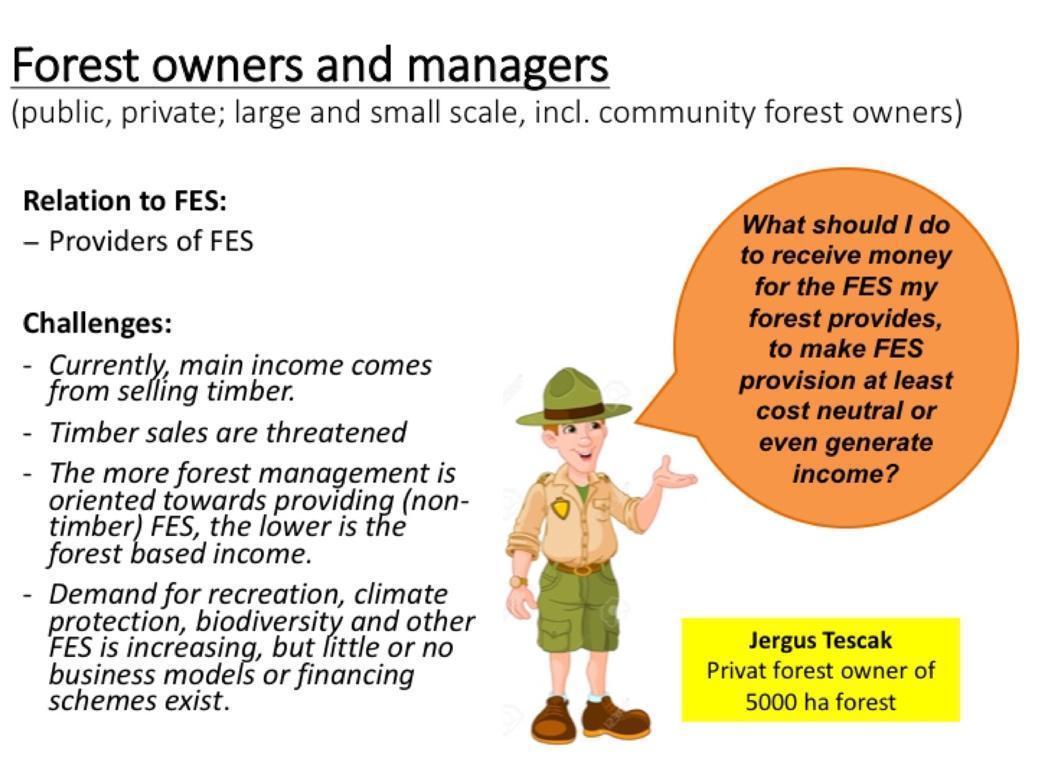

- Figure 8: Forest Owners – Persona

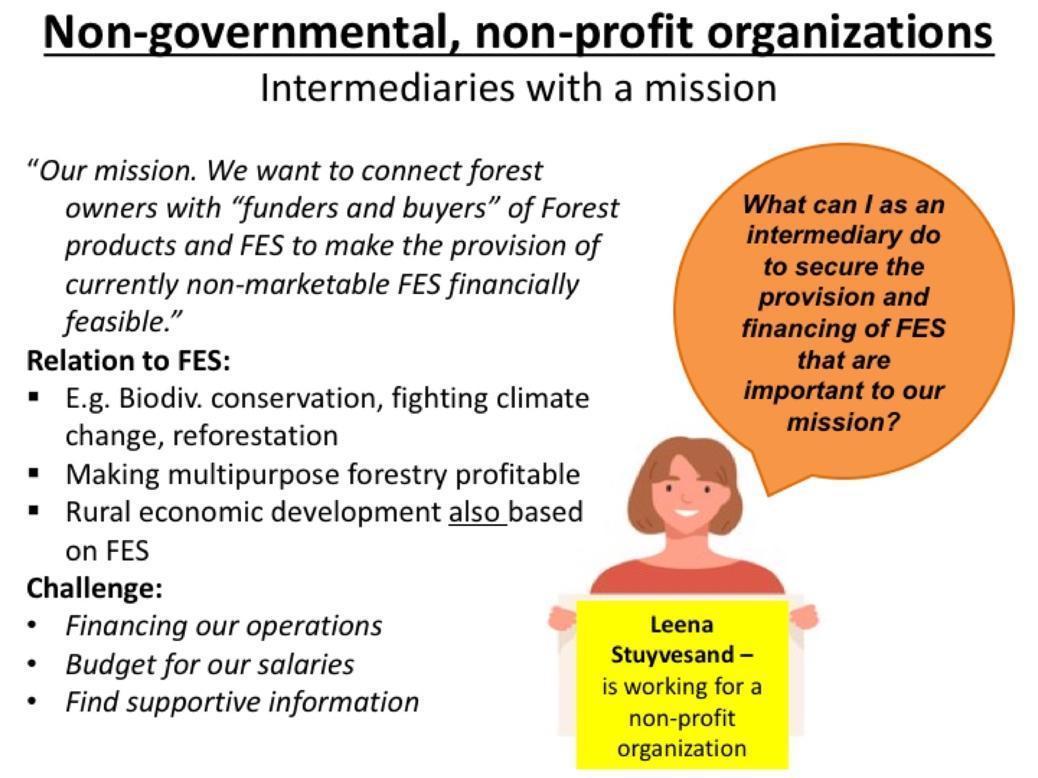

- Figure 9: Non-governmental organisation – Persona

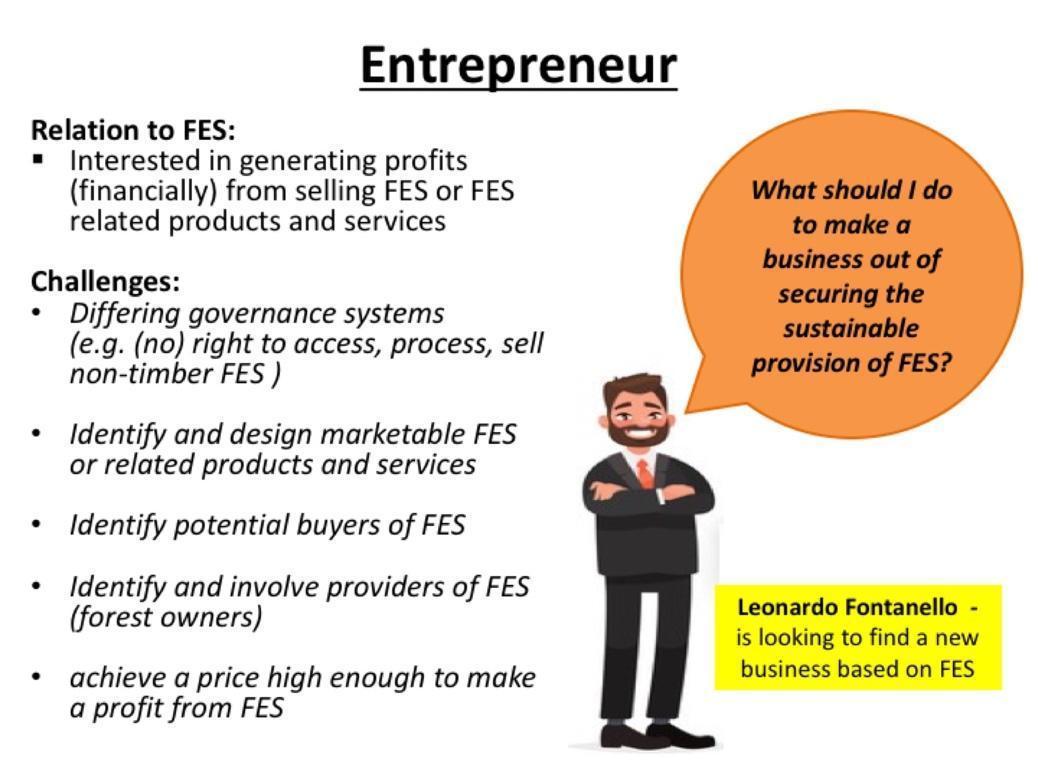

- Figure 10: Entrepreneur – Persona

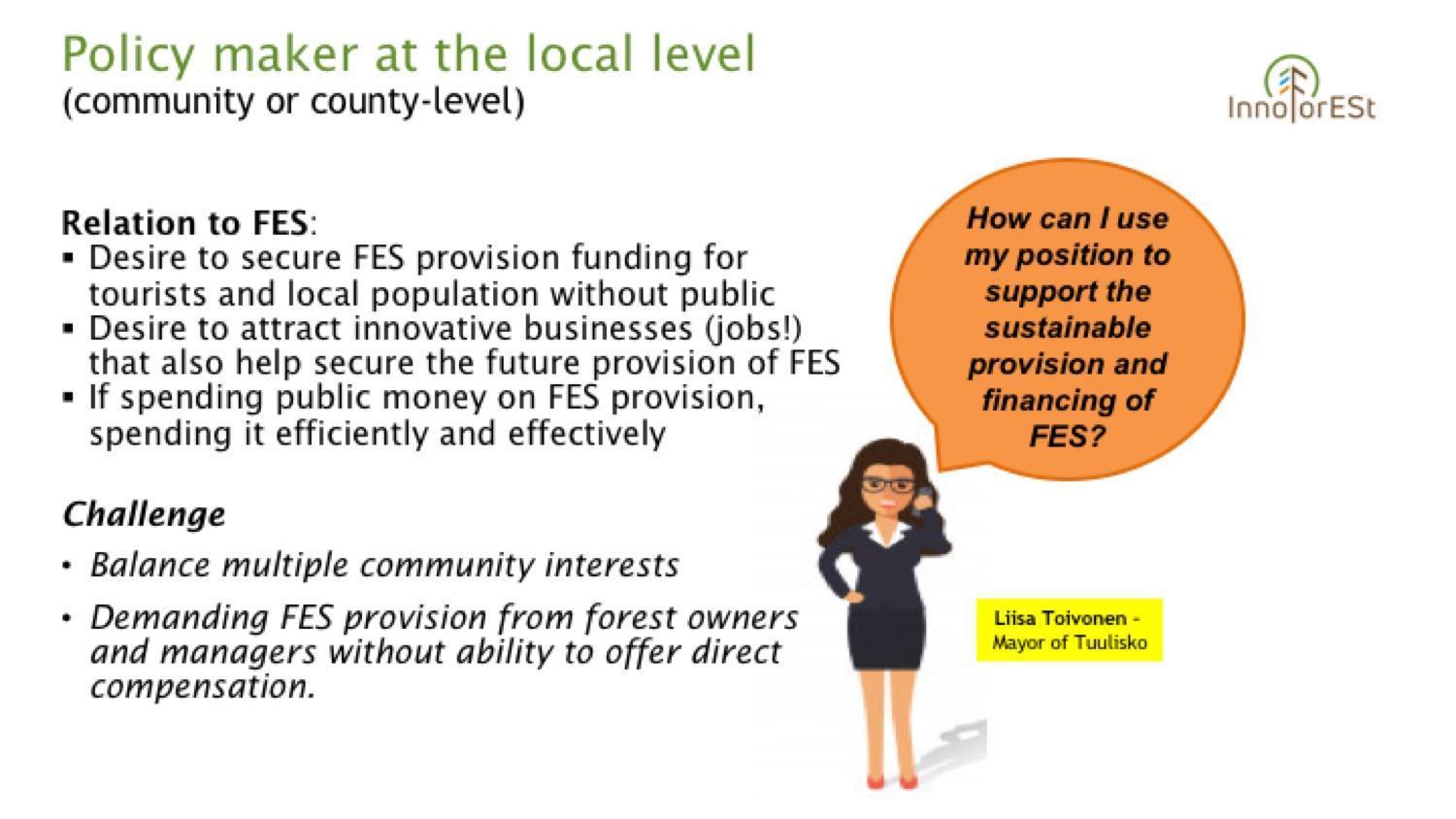

- Figure 11: Local policy-maker – Persona

- Figure 12: National and EU policy-maker – Persona

- Figure 13: Scientist – Persona

- Figure 14: IR Finland – Lessons Learned

- Figure 15: IR Germany – Lessons Learned

- Figure 16: IR Czech Republic/Slovakia – Lessons Learned

- Figure 17: IR Italy – Lessons Learned

- Figure 18: IR Austria- Lessons Learned

- Figure 19: IR Sweden – Lessons Learned

Abbreviations

| AT | Austria |

| CINA/CTA | Constructive Innovation Assessment / Constructive Technology Assessment |

| CZ | Czech Republic |

| D | Deliverable |

| DE | Germany |

| DIY | “Do it yourself” |

| EC | European Commission |

| EUSTAFOR | European State Forest Association |

| FES | Forest ecosystem services |

| FI | Finland |

| FVA | Forest Research Institute Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany |

| InnoForESt | Smart information, governance and business innovations for sustainable supply and payment mechanisms for forest ecosystem services |

| IT | Italy |

| IR | Innovation Region |

| LULUCF | Land use, land-use change, and forestry |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organisation (non-profit) |

| SETFIS | social-ecological-technical-forestry-innovation systems |

| SK | Slovakia |

| SW | Sweden |

| WP | Work Package |

1 Introduction

1.1 Objectives of this report

This report is written in the context of InnoForESt project objective 4, which is to derive „policy and business recommendations for forest managers, policy-makers, businesses, and NGOs, from the local and regional to the national and EU level (…) for establishing, assessing and implementing innovative governance strategies, Payment mechanisms, business models and financing mechanisms for forest ecosystem services across Europe.“ (InnoForESt Grant Agreement, p. 130). It summarises relevant insights generated and lessons learned by the international, inter- and transdisciplinary and multi-actor based project consortium over the course of almost three years of research and real-world innovation development. Based on research results and systematically documented experiences, the report aims to formulate targeted policy and business recommendations and options for action for forest owners/managers, non-profit NGOs & associations, entrepreneurs, local, national and EU policy-makers, as well as scientists, on how they can use their position and resources to advance governance innovations for the sustainably provisioning and financing of FES.

While the actual outreach to specific target groups as well as the production of associated outreach materials is beyond this deliverable’s scope, it does provide the content necessary to produce and disseminate such materials. To this aim the report is structured in a way that allows selective reading: The main chapters ‘InnoForESt in Context’, ‘Materials and Methods’, ‘Targeted recommendations and options for action’, and ‘Concluding remarks’ provide the overall relevant information. The sub-chapters 2.1 to 2.6 can be read selectively. They present recommendations regarding stakeholder network development, facilitated innovation development, maintaining direct links to FES provision, and payment mechanisms for FES provision addressed specifically to the following actors:

- Forest owners and managers (chapter 2.1)

- NGOs & associations (chapter 2.2)

- Entrepreneurs (chapter 2.3)

- Local level policy-makers (chapter 2.4)

- National & EU level policy-makers (chapter 2.5)

- Scientist and research funding entities (chapter 2.6)

The annex contains supplemental information for each IR according to their primary FES governance innovation approach. They contain information regarding the development of their respective stakeholder networks, innovative payment mechanisms, and their (potential) implications for forest management and FES provision at three points in time: before working with InnoForESt, after having worked with InnoForESt for almost three years, and finally the IRs’ visions for the future.

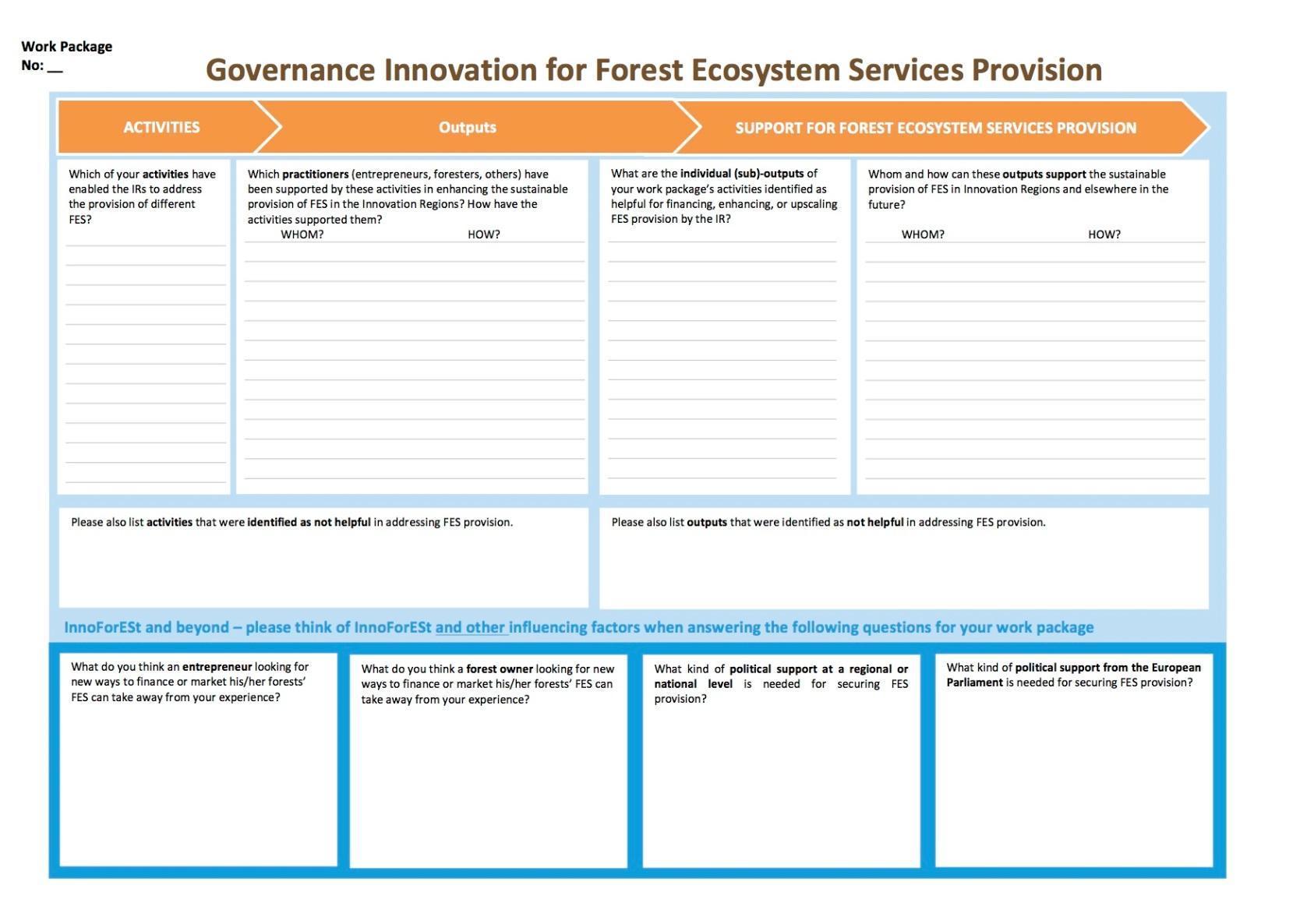

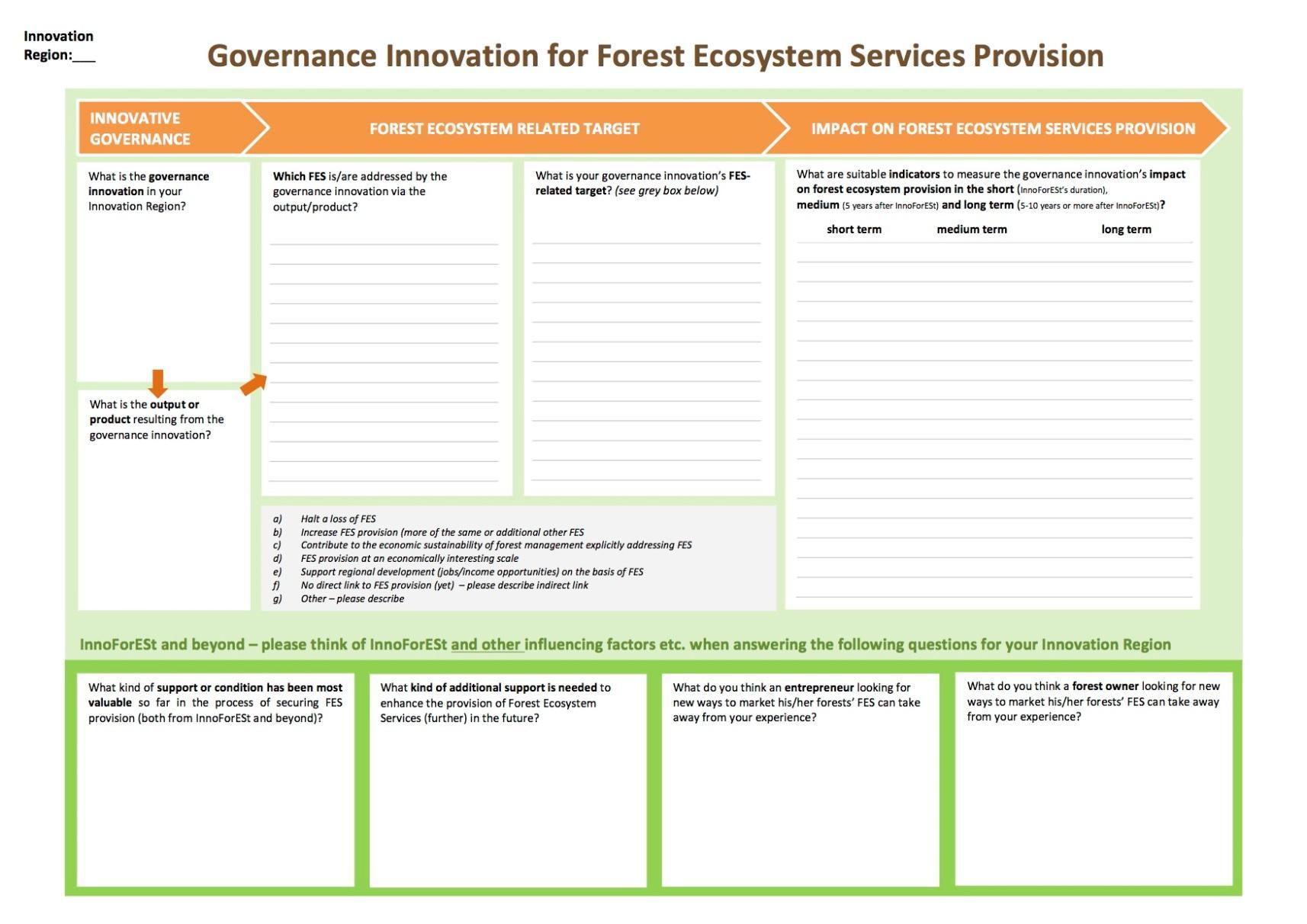

The annex further includes templates used in the context of an interactive session at a consortium meeting in 2019, which focused on the governance innovations (potential) impact on FES provision in the IRs and related recommendations to draw from the IRs’ and WPs’ insights. The templates are referenced in the text.

1.2 InnoForESt in Context

European forests provide numerous benefits to society, ranging from purifying air and water to conserving biodiversity, protection from landslides, floods and avalanches, to scenic beauty, recreational, educational and cultural settings, and tangible forest products like fuel, timber, woody biomass, but also edible mushrooms, berries, ornamental plants and many more. Yet, the continued availability of the various regulating, cultural and provisioning Forest Ecosystem Services (FES) is in jeopardy; European forests and the forestry sector are affected by global environmental problems, increasing urbanisation, industrialisation pressures, and market dynamics that prioritise provisioning above regulating and cultural FES. Forest owners are usually unable to generate revenues off the broader range of ecosystem services their forests provide, forcing them to base management decisions on marketable goods, mainly timber production.

At the same time, societal demand for often non-marketable cultural and regulating FES, such as recreation, biodiversity, water retention and carbon sequestration, continues to increase on public and private land. Currently, the provision of FES, particularly regulating and cultural FES in Europe, is largely facilitated through public land management. On public land, the opportunity costs incurred due to reduced timber sales are largely accepted. Different countries provide different policies, laws and regulations, administering forest and FES management also on private land, including some financial support programes for changes in private forest management such as compensating income lost due to e.g. nature conservation requirements. Still, existing strategies and initiatives at the European and pan-European level have not been able to effectively and sufficiently address the under-provision or under-valuation of regulating and cultural FES and the costs for their targeted management, especially in private forests. Established market mechanisms appear to provide insufficient incentives to realise this objective. As a result, demand for non-marketable FES continues to exceed its short-term economically viable supply, causing social costs and often one‐sided policy and forest management decisions.

Politically, there is an interest to increase private sector involvement in securing the provision of FES. This leads to the interest in researching “innovative governance mechanisms” that might improve this situation.

Roughly speaking, governance is about 1) who decides what the objectives of a certain decision like a management strategy or development approach are, what to do to pursue them, and with what means, 2) how those decisions are coordinated e.g. hierarchically, by networks or markets 3) who holds power, authority, and responsibility, e.g. individuals, businesses, organisations, and 4) who is (or should be) held accountable, e.g. for implementation and potential liabilities.

Governance mechanisms, especially environmental governance mechanisms, are consequently the ever-changing forms of social coordination in which any management decision, including those concerning FES, take place. Depending on the topic, a variety of actor groups are engaged in interdependent relationships and power relations. Simplistically, they come from three main but overlapping spheres: state, market, and civil society. These actors interact with one another in formal or informal ways with varying influence.

In general, these are multi-level interactions (i.e., local, national, international/global) with a broad variety of mutually influencing ‘rules of the game’ or governance modes ranging from hierarchical (like laws and regulations, but also dominance) to market-based (esp. income oriented, supply and demand driven) and cooperative/collective forms.

Against this background, InnoForESt’s objective has been to identify, analyze, and enhance innovative governance mechanisms targeting especially private market-based approaches that show potential to become alternative or complementary means to currently predominantly public efforts of securing FES provision and financing.

A number of on-going policy processes offer windows of opportunity to proactively foster the provision of FES – in particular regulating and cultural FES – though innovative governance mechanisms. First and foremost, the European Green Deal and associated strategies, particularly the EU Farm to Fork Strategy , the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 , the EU Climate Action , LULUCF , and the development of the EU Forest Strategy . Most of these initiatives emphasize forests’ role in sequestering carbon and biodiversity protection. Several mention the need for creating incentives for forest management to achieve these objectives – e.g. the EU Farm to Fork strategy explicitly states the need for compensation payments and an associated system of robust certification rules for carbon sequestration. Other EU policies also touch on forests’ role in carbon sequestration, such as the EU emissions trading system , or the EU Taxonomy for sustainable activity .

InnoForESt findings suggest that in addition to payments related to carbon sequestration or biodiversity conservation, there is value in targeted support for local level initiatives that aim to secure provision of these and other FES through network based approaches. The potential of these policy strategies to foster FES provision can only be realized if the goal of securing FES provision is integrated into existing and emerging governance and funding schemes. It should be addressed as an explicit objective that is pursued through targeted political steering and public support for private profit and non-profit business innovations. In this process, the focus should rest on securing in particular the full range of regulating FES, such as air and water quality, soil protection, flood and erosion control, biodiversity conservation as well as carbon sequestration.

The provision of FES is related to further policy initiatives, though not all reference forests and their potential as of yet. For example, the new bio-economy strategy is an action plan to develop a sustainable and circular bio-economy that serves Europe’s society, environment and economy. It is part of the Commission’s drive to boost jobs, growth and investment in the EU. It aims to improve and scale up the sustainable use of renewable resources to address global and local challenges such as climate change and sustainable development. The document states that in a world of finite biological resources and ecosystems, an innovation effort is needed to feed people, and provide them with clean water and energy. Yet the strategy mainly focuses on maritime and agricultural biomass, plastic recycling, converting and upcycling waste or transforming industrial by-products into bio-based fertilisers. Very little reference is made to the role and potential of forests in this domain.

Finally, widely established market-based instruments influencing the provision of FES include certification schemes for sustainable forest management; paramount are here the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) and the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). They are expected to secure, legitimise or even open new markets for timber from sustainably managed multifunctional forests and ideally provide price premiums. They are actively improving management practices of forest owners, which also directly address the provision of different regulatory and cultural FES. As of today, more public than private forests are covered by these certification schemes.

Given the different biogeographic and national legal and economic frame conditions of forestry within Europe it is not easy and often not supported to unify forest policy at European level. However, there are certain overarching notions which prevail throughout all forests of Europe; one being that forestry is one of the central sectors that serve a role in mitigating climate change and another promoting the societal and ecological value of non-marketable FES.

Although the importance of regulating and cultural FES is directly or indirectly recognised in most EU and national forest related policies, strategies and laws for Biodiversity conservation, Forest and the Forest based sector, and the Bioeconomy (see Primmer et al. 2018/D2.1), forest owners are generally hardly rewarded for their provision.

One prominent programme for supporting forest management for the provision of currently non-marketable FES is the Natura 2000 network payment, which provides lump-sum payments per hectare managed primarily for biodiversity conservation which is assumed to make up for “income forgone”. The programme shows achievements all over Europe, but much slower than scheduled, as in many cases these public compensation payments are not acknowledged to be equivalent to the income forest owners make managing the forest for harvestable timber, especially not in fertile forest stands.

Consequently, innovative governance mechanisms that better include private business-related approaches are sought to complement, upgrade or even supersede legal requirements and publicly funded FES development programs.

Local level initiatives throughout Europe are already working on new ways to align forest management and the development of forest-based products with the provision of all types of ecosystem services based on increasing and diversified societal demands. These initiatives are often driven by forest-related private business endeavors in combination with an inherent idealism to promote but also benefit from the appreciation and valuation of regional FES, alas with variable levels of success, economic sustainability and potential for replicability. Policy-makers on all levels are interested in options for action to better support these kinds of initiatives for the sustainable provision and financing, in particular of currently non-marketable FES.

The InnoForESt project – a Horizon 2020 European Innovation Action – has therefore been created to support enhanced coordination in policy making, and to facilitate the improvement, development and mainstreaming of policy and business innovations dealing with or affecting FES. This shall foster the sustainable and economically viable provision of a broad(er) range of FES across Europe, in particular those that lack market values but are of tremendous importance for societal wellbeing, i.e. cultural and regulating FES. For this endeavour, an inter- and transdisciplinary consortium has been formed by 16 institutional project partners from nine European countries to include about the same amount of scientists from different universities and research institutes on the one hand as well as practitioners from different fields and organisational affiliations on the other.

The scientists involved in this project represent a variety of disciplines. Their academic work has been organised in individual Work Packages (WPs), each with a particular thematic focus. The practitioners work in different capacities and represent, for example, NGOs, public administration, and private business engaged in local level initiatives related to FES provision and financing. Finally, some of the scientists are working very closely with or even for a practice partner organisation, taking on a kind of ‘hybrid’ role and acting as a liaison between academia and the implementation level.

From late 2017 to 2020, the InnoForESt consortium has accompanied and analyzed the experiences of six so-called ‘Innovation Regions’ (IRs) in their pursuit of developing innovative governance mechanisms that aim to secure the future provision and financing of FES. Located in seven European countries, the IRs vary with regards to the forest bio-geographical region, the particular (set of) FES in focus, and the innovative governance mechanism they pioneer to secure their future provision.

Nevertheless, each IR can be subsumed either under a primarily stakeholder network based approach and/or as focusing primarily on the development of a payment mechanism for FES provision (see also Table 1, more details on each IR’s FES related developments can be found in the Annex). Scientists and practitioners have worked together in what is referred to as ‘IR Teams’ and scientists have taken the role of facilitating, supporting, and analyzing the respective innovation development processes in the InnoForESt context.

| Innovative governance mechanism | Innovation Region | Forest Ecosystem Service(s) targeted |

|---|---|---|

| Payment mechanism | Finland “Habitat Bank” | regulating FES: Biodiversity |

| Payment mechanism | Germany (Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania) “Forest Share/Waldaktie” | regulating FES: CO2 Sequestration |

| Payment mechanism (CZ) & Network approach (SK) | Czech Republic and Slovakia (Cmelak resp. Hybe) “Collective Governance of Ecosystem Services” |

regulating FES: CO2 sequestration, biodiversity |

| Network approach | Italy (Autonomous Province of Trento) “Forest pasture system management” | regulating FES: Water regulation, natural hazards protection, biodiversity cultural FES: Tourism and recreation,rural tradition |

| Network approach | Austria (Eisenwurzen) “Value chains for forest and wood” | provisioning FES: Timber (hard- and softwood) cultural FES: Tourism, recreation, regulating FES: biodiversity |

| Network approach/hierarchy | Sweden (Helsinki) “Love the forest” | cultural FES: Tourism, recreation and cultural values |

1.3 Materials and Methods

This report is based on different types of primary and secondary sources, including project deliverables, project internal documents (see section ‘Documents’ below), as well as data gathered in the context of a project workshop on the topics of this report (see also sections ‘Survey’ and ‘Recommendations Workshop’). A first version of this report was compiled by WP6/FVA in July 2020 . Draft versions of it were shared with scientists who were working on relevant deliverables at the time of writing, to make this report as comprehensive as possible.

Further insights documented in deliverables due after July 2020 (see also list directly below) were then added between August and November 2020 by the respective authors before the report’s final submission.

1.3.1 Secondary Sources

Project documents, including draft versions of upcoming deliverables, which provide the foundations for this report are:

- InnoForESt Grant Agreement

- D2.1: Primmer, E., Orsi, F., Varumo, L., Krause, T., Geneletti, D., Brogaard, S., Loft, L., Meyer, C., Schleyer, C., Stegmaier, P., Aukes, E., Sorge, S., Grossmann, C., Maier, C., Sarvasova, Z., Kister, J. 2019. Mapping of forest ecosystem services and institutional frameworks (version v1.1).

- D2.2: Geneletti, D., Primmer, E., 2019: Institutional and Biophysical Maps of FES in Europe. https://syke.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=e27ae600fad1451fa3ed4109ae309856.

- D2.3: Varumo, L., Primmer, E., Orsio, F., Geneletti, D., Krause, T., Brogaard, S., 2020. Inventory of innovation types and governance of innovation factors across European socio-economic conditions and institutions (delivered April 2020).

- D3.1: Sorge, S., Mann, C., 2019. Analysis framework for the governance of policy and business innovation types and conditions (delivered in October 2018, revised August 2019).

- D3.2: Kluvánková, T., Špaček, M., Sorge, S., Mann, C., Schleyer, C., 2020. Application summary of prototypes for ecosystem service governance modes – demonstrator (delivered January, 2020).

- D4.1: Sattler 2019. Mixed method matching analysis (delivered October 2019).

- D4.2: Aukes, E., Stegmaier, P., Schleyer, C., 2020. Set of reports on CINA workshop findings in case study regions, compiled for ongoing co-design and knowledge exchange (delivered April 2020).

- D4.3: Loft, L., Stegmaier, P., Aukes, E., Sorge, S., Schleyer, C., Klingler, M., Zoll, F., Kister, J., Mann, C. 2020. The emergence of governance innovations for the sustainable provision of European forest ecosystem services: A comparison of six innovation journeys (delivered October 2020)

- D5.1: Aukes, E., Stegmeier, P., Hernández-Morcillo, M. 2019. Interim Ecosystems Service Governance Navigator & Manual for its Use (delivered January 2019).

- D5.2: Schleyer, C., Kister, J., Klingler, M., Stegmaier, P. Aukes, E. 2018. Report on stakeholders’ visions, interests and concerns (revised version as of September 2019).

- D5.3: Aukes, E., Stegmeier, P., Schleyer, C., 2020. Final report on CTA [CINA] workshops for ecosystem service governance innovations: Lessons learned; (delivered 3. Dec 2020)

- D5.4: Schleyer, C., Kister, J., Klingler, 2020. Design on training events to develop innovation capacities and innovation knowledge.

- D5.5: Aukes, E., Stegmaier, P., & Hernández-Morcillo, M. (2020). Ecosystems Service Governance Navigator & Manual for its Use.

- D6.2: Maier, C., Grossmann, C. 2019. Interim Report on Replicability and Upscaling Potentials of Governance Innovations (favoring provisioning and financing of forest ecosystem services) (delivered July 2019).

- D6.4: Morand, S., Budniok, M., Grossmann, C.M., Maier, C., Chubb, L., Fox, M. 2020. Updated Communication Plan – provides the overall communication strategy of project results and recommendations (delivered Dec 2020)

1.3.2 Primary Sources

Findings documented in (draft versions) of the above listed project documents, served as the first basis for this report and for preparing a ‘Recommendations Workshop’ and a ‘Pre-Recommendations-Workshop Survey’. The results of these two primary sources served as additional important pillars to the writing of the present report.

Pre-Recommendations-Workshop-Survey

In April 2020, WP6-FVA organised a 1.5-day workshop with representatives of all WPs and most IR teams. Due to COVID-19 related travel restrictions, the workshop was held virtually. It served to reflect and discuss each WP’s contribution to the project’s overarching objective of securing the future provision and financing of FES with a strong focus on the practitioners’ perspective on the perceived impact on securing FES provision and financing in their individual IRs (see also ‘Recommendations Workshop’ below). In preparing the workshop, a pre-recommendations-workshop survey was launched within the project consortium. Work package representatives and IR teams were asked to respond in writing to specific questions related to the impact InnoForESt activities and outputs had in the IRs, which elements of the InnoForESt process are perceived as recommendable to other initiatives, as well as their conclusions which recommendations could be provided to policy and business representatives for securing the provision and financing of FES (see figure below for an overview of the questions asked). The responses generated valuable insights on numerous positive developments in the IRs, and the impact project activities and outputs have had in the IRs. However, responses to project overarching questions remained rather specific to particular WP or IR contexts, but provided a basis for a facilitated discussion among all project partners in a workshop setting. Findings from this survey and the workshop itself are the primary sources of information for the recommendations presented in this report. The questions asked build on a group work session during the annual project consortium meeting 2019. Teams of practitioners and scientists were tasked to discuss the implications of their InnoForESt related work on forest management and FES provision, and document results on a poster template. These included first thoughts on recommendations to policy-makers and practitioners. While too early for substantial results, the discussions sparked important discussions and reflections on InnoForESt related work (see annex for templates used in the workshop session).

Pre-Recommendations-Workshop Survey – Questions directed at InnoForESt scientists

Lessons learned – key insights from your Work Package

What are the top three key insights you gained through your InnoForESt work on the following issues:

- What are characteristics of a promising stakeholder network aimed at securing the provision and financing of FES?

- What are key factors furthering the inclusion of key stakeholders and building a strategic stakeholder network, particularly related to actors owning or managing forests?

- What are key factors hindering the inclusion of key stakeholders and building a strategic stakeholder network, particularly related to actors owning or managing forests?

- What are characteristics of a promising Payment mechanism designed to secure the provision and financing of FES?

- What are key factors furthering the development of a Payment mechanism for FES?

- What are key factors hindering the development of a Payment mechanism for FES?

- Required support

- Please list the three issues you think are most important

- InnoForESt will end in 2020, yet the digital platform created during the project will remain active for 5 years. In your opinion, how can the digital platform (continue to) support our Innovation Regions in the future in securing the provision and financing of FES? What kind of content or support would you like to see on the digital platform?

- Do you think further research is needed to secure the provision and financing of FES in the future? If so, what are questions you think would aid the pursuit of innovative governance mechanisms for securing the provision and financing of forest ecosystem services?

- How can it be ensured that future research on governance innovations (continues to) contribute/s to securing the provision of forest ecosystem services in the future?

Recommendations

Based on your experience, what would you recommend the following actors to do when looking for ways to secure the provision of FES? What can he or she learn from your experience?

- Private forest owners

- Public forest owners, e.g. state, municipality

- collective forest owners

- non-governmental organizations

- entrepreneurs

For each of these actors, please complete the following sentences:

- To learn from others about ways to secure the provision of forest ecosystem services and find funding for it, I would recommend to….

- To build a stakeholder network and reach out to key stakeholders, I would recommend to…

- To design a payment mechanism to fund the provision of FES, I would recommend to…

- To actually make money off of the FES provided by your forests, I would recommend to…

- Other recommendations you would like to provide to these actors:…

Based on your experience, what do you think policy-makers could to do support you and initiatives like yours in their efforts to secure the provision and financing of FES?

- Policy-makers at the local level

- Policy-makers at the national level

- Policy-maker at the EU level

Pre-recommendations-workshop survey – Questions directed at InnoForESt IR practitioners

Past-Present-Future

- You have worked with InnoForESt for almost 3 years now. How would you describe your initiatives’ status with respect to its stakeholder network, payments for FES provision, impact on forest management and on FES provision before you worked with InnoForESt, today, and in your vision for the future?

- What would be suitable targets for the short/medium/long term future development of your Innovation Region?

Desired Support

Please focus on the 3 most important issues

- What kind of additional support would you have liked to have from a research project like InnoForESt but did not (yet) receive?

- InnoForESt will end in 2020, yet the digital platform created during the project will remain active for 5 years. In your opinion, how can the digital platform (continue to) support your Innovation Region in the future? What kind of content or support would you like to have through the digital platform?

- Do you think further research is needed to secure the provision and financing of FES in the future? If so, what are questions you would like to ask researchers to find out?

Recommendations

Based on your experience, what would you recommend the following actors to do when looking for ways to secure the provision of FES? What can he or she learn from your experience?

- Private forest owners

- Public forest owners, e.g. state, municipality

- collective forest owners

- non-governmental organizations

- entrepreneurs

For each of these actors, please complete the following sentences:

- To learn from others about ways to secure the provision of forest ecosystem services and find funding for it, I would recommend to….

- To build a stakeholder network and reach out to key stakeholders, I would recommend to…

- To design a payment mechanism to fund the provision of FES, I would recommend to…

- To actually make money off of the FES provided by your forests, I would recommend to…

- Other recommendations you would like to provide to these actors

Based on your experience, what do you think policy-makers could to do support you and initiatives like yours in their efforts to secure the provision and financing of FES?

- Policy-makers at the local level

- Policy-makers at the national level

- Policy-maker at the EU level

- To support me in my efforts to learn from others about ways to secure the provision of forest ecosystem services and find funding for it, they could…

- To support me in my efforts to expand my network and reach out to key stakeholders, they could …

- To support me in my efforts to design a payment mechanism to fund the provision of FES, they could…

- To actually make money off of the FES provided by your forests, I would recommend to…

- Other recommendations you would like to provide to policymakers

Throughout the project one main challenge was to provide for eye-level communication in an international, intercultural and transdisciplinary project, between scientists and practitioners working in different local contexts and languages. One important objective of the ‘recommendations workshop’ was to create a safe space for all 30 participants, where everyone would have the equal opportunity to contribute to the workshop and to share their point of views. To facilitate such collaborative, interactive setting, the WP6-FVA team incorporated Design Thinking Principles into the workshop concept: a problem-solving approach serving to “accomplish key strategic objectives, whether those objectives involve traditional business outcomes […] or social outcomes […]” (Liedtka et al. 2017, p. 8). It fosters the capability for innovation and reflection and supports the development of “more innovative and effective outcomes and processes that create better value for the stakeholders they serve and that make organisations more effective in meeting their missions” (ibid, p. 8), by engaging “stakeholders in co-creation” (ibid, p. 6).

Based on the pre-workshop survey the FVA team prepared several templates in GroupMap . GroupMap is an online tool for planning, brainstorming, reflecting, and documenting group discussions that mirror Design Thinking principles. It provides sets of different templates addressing the diverse needs connected to online meetings. Additionally, GroupMap offers a clear and appealing design which makes it easy to work with it – even for people who never used such online tools before.

The first part of the workshop was dedicated to a reflection of the main project activities and their impacts on IR developments. Both the template and the discussion were structured into four different parts: (1) Activities and their impact, (2) Suggestions for improvement, (3) ‘How to’ – a practitioner’s guide to ‘Do it Yourself’, and (4) How to ensure an impact on FES provision. The answers provided by WPs and IR teams in the preparatory pre-workshop-survey were integrated into the template – thus, they served as a starting point for the discussion and a reminder of the central topics. Prepared guiding questions helped keep discussions focused on the respective goal . This approach enabled a lively debate about the activities’ impact on local level initiatives in their efforts to secure FES provisioning and financing. A similar session aimed at a collective reflection on the impact and which of the InnoForEst outputs produced are especially recommendable for use outside/beyond and after the project.

The second part of the workshop focused on deriving common policy and business recommendations for the aforementioned six target groups (forest owners/managers, NGOs & associations, entrepreneurs, local, national and EU level policy-makers). All contributions were to be based on insights generated during the InnoForESt project. In preparation for the workshop, the FVA team developed a hypothetical description of a ‘Persona’ that represents each target group to be addressed. In Design Thinking, a Persona is a portrait of a fictive person.

In the case of the InnoForESt workshop, the Personas were designed by using information provided in the survey responses and by integrating further professional knowledge of the FVA team on likely perspectives of the different stakeholder groups. This approach resulted in a diverse set of characters, representing the needs and interests of forest owners/managers, non-profit NGOs, entrepreneurs, local, national and EU policy-makers, and scientists. Each Persona was introduced to the workshop participants with their FES-related interests and challenges, as well as resources available to them (see chapter 2). The discussion was guided by a set of questions tailored to the particular characteristics of each Persona. The group moderator ensured that the discussion of the targeted policy and business recommendations would directly be derived from the findings of and/or experiences made within InnoForESt. For this second part of the workshop, the participants were split into two groups. The smaller group size allowed for a more intense discussion with more room for everybody to share their own perspectives and thoughts. As the groups discussed two different Personas in parallel before switching personas, each working group had the chance to pick up on the recommendations developed by the former group and to elaborate them or to promote completely new ideas.

The results are documented in a Group Mind Map, another GroupMap template . Mind mapping is a technique to visualise and analyze ideas as well as to illustrate their connections in a clear manner. This process fosters analytical thinking and, at the same time, it allows for a creative thought process . This relates to the characteristic of Design Thinking of being possibility-driven and option-focused: it concentrates on “generating multiple options” (Liedtka, Salzman, Azer 2017, p. 6) and avoids to focus on “one particular solution” (ibid, p. 6). The Personas and the Group Mind Maps facilitated fruitful discussions and enhancements of the preliminary policy and business recommendations in a short period of time. Altogether, the methods and templates used during the workshop were considered as helpful tools with an attractive design which helped to organise a “well-structured” and “goal-orientated” workshop under challenging conditions due to COVID-19 (feedback by participants). The information collected during the survey and the workshop was complemented by direct communication and feedback from IR teams to the authors of this report.

2 Targeted recommendations and options for action

Three years of InnoForESt have sparked important developments in the IRs towards developing or improving innovative governance mechanisms that are expected to secure FES provision and financing. So far, all innovation developments are ongoing processes that may result in a self-sustaining, economically viable business and/or cooperation) model of FES provision and financing. The recommendations outlined below are therefore based on InnoForESt’s experiences initiating and supporting processes that show potential to reach the objective of self-sustaining business models for FES provision and financing.

Five overarching themes have emerged despite the variability in IRs’ local contexts, different FES-related objectives, and asynchronous developments during InnoForESt. Generally speaking, they relate to issues that demand consideration during the entire process of working towards an innovative governance mechanism for FES provision and financing. As such, they serve as the structuring backdrop to the target-group specific recommendations and options for action that follow. The project results suggest that all six targeted actor groups can contribute to securing FES provision and financing by catering to one of more of these overarching themes, or by addressing them through different means.

Maintaining Direct Link to FES Provision

Boosting governance innovations for the sustainable provision and financing of FES is the main aim of the project and its activities. While pursuing complex participatory stakeholder network building and governance innovation oriented processes it is important not to lose sight of the topical objective. FES are closely linked to a diversity of economic sectors, related to partially contradicting objectives, and associated stakeholders. Each of these connections can offer an opportunity for securing FES provision and financing. Maintaining the link to and continuously reflecting potential implications for FES provision and financing along the path of developing stakeholder networks, visions for the future and possible approaches is of fundamental importance for the innovation process. This entails including forest sector stakeholders from an early stage in any stakeholder network activities, particularly forest owners and managers. Gaining an understanding about the current supply and demand of various FES, possible customers willing to pay for (particular) FES, as well as opportunities and potential trade-offs associated with increasing the quantity and quality of FES-based (business) initiatives are key steps to maintain a focus on the objective.

In the further development of an innovative governance mechanism, monitoring changes in the quality and supply of relevant FES is important to understanding the impact of the new governance mechanism on the provision of different FES. As InnoForESt has shown, a governance innovation’s potential impacts on FES can vary significantly: it can be rather direct, such as in a compensation scheme funding forest restoration activities for biodiversity conservation, (i.e. IR FI); or indirect, such as a wood value chain that creates a market for regional hardwoods and thereby supports a forest conversion towards mixed species forest stands intended to enhance their resilience and biodiversity (i.e. IR AU). Likewise, there is a need to differentiate potential objectives a governance mechanism can have/pursue with respect to FES provision: as our IRs illustrate, the explicit aim or implicit effect can be to either maintain a current level of FES provision (e.g. IR SK) or to increase the quantity and or quality of FES provision (i.e. IRs DE, FI, IT).

Acknowledging this variability and formulating FES-related objectives accordingly are fundamental to developing effective governance mechanisms. Clearly formulated FES targets are also the basis for a monitoring of a governance mechanism’s FES impact in the long term (see Maier and Grossmann 2019/D6.2).

Monitoring is of particular importance because FES provision is linked to a number of different policy fields and economic sectors. Though, when integrating multiple objectives for mutual benefit, for example, FES provision and rural economic development, a close monitoring of effects on the supply of various FES is needed. InnoForESt has identified several links between the goal of sustainable provision of FES and rural development. The IR Austria, in the region of Eisenwurzen, for example, works towards building a regional forest-wood-value chain for the purpose of maintaining a vibrant rural economy. Some of the local businesses (plan to increasingly) process regionally sourced, autochthonous hardwood into innovative products. By creating a market for regional hardwood, the production and sale of these products on a larger scale has the potential to refinance forest management decisions that include forest conversions towards a mix of tree species, which in turn would lead to more biodiverse and climate resilient forests in the region. Thus, while rural development based on forest resource extraction does not automatically imply a positive impact on provision of regulating and/or cultural FES, it certainly has the potential to do so – if the non-tangible FES are given sufficient and timely consideration. Similar interrelated direct and indirect positive effects can be expected and need to be monitored in other fields, such as (nature-based) tourism or forest-related educational programmes.

As an attempt to embed the InnoForESt innovations in the larger EU biophysical and institutional context, an extensive mapping activity elaborated on the possibilities to identify regions with similar and with differing biophysical FES supply and as well as on the use policy analysis for the assessment of FES demand (see Box “Biophysical and Institutional Mapping”). The resulting datasets and maps were expected to contribute to an assessment of replication and upscaling potentials of the innovation examples (Maier and Grossmann 2019/D6.2, see also text box below).

Biophysical and Institutional Mapping

Replicating or upscaling innovations requires a deep understanding of the conditions and contexts that support a particular and successful FES related innovation, both in ecological and institutional terms. In the attempt to embed the InnoForESt innovations in the larger EU context, extensive mapping was conducted to capture the various biophysical and institutional, structural and procedural conditions influencing supply and demand of FES.

FES supply was investigated by means of spatial analysis at the European scale focused on the following services: wood, water supply, erosion control, pollination, habitat protection, soil formation, climate regulation and recreation. The maps are available here: https://syke.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=e27ae600fad1451fa3ed4109ae309856. This analysis allowed us to identify hotspots and bundles of FES. Hotspots represent forest areas characterised by a very high provision of a specific ecosystem service, whereas bundles represent areas characterised by a similar level of supply of the same set of ecosystem services (see maps below).

In terms of FES demand, we propose that medium term societal demand could be derived from formal goals and argumentation in public strategies. A detailed analysis of policy documents covering European strategies, national or regional strategies and/or legislative documents from all InnoForESt case study countries or regions was conducted.

The information derived from biophysical and institutional mapping could then be used, for example, to develop sustainable landscape plans, design nature-based solutions, assess the dependence of a region on ES produced elsewhere or estimate the role played by a region in guaranteeing ES to one or more regions, as well as to identify ES for which further investment is needed.

Forest Ecosystem Service Hotspots

Forest Ecosystem Service Bundles

Contribution by Geneletti and Primmer 2020Bringing diverse stakeholders together

The IRs involved in InnoForESt went through a systematic and comprehensive process of identifying and reaching out to stakeholders interested in the development of innovative FES-related business and governance models. In the first project year, InnoForESt scientists worked directly with IR practitioners to conduct a stakeholder analysis for each respective IR. The portfolio of methods used and the results were documented in Schleyer et al. 2018/D5.2.

IR practitioners reported benefiting greatly from the analysis as it:

- resulted in a better understanding of the spectrum of potential stakeholders, and their interests, including their openness towards innovative ideas.

- supported the decision to include/exclude certain stakeholders.

- facilitated a reflection of past stakeholder-related decisions that were made before the formal stakeholder analysis was conducted.

Several IR practitioners described the stakeholder analysis as an important step for the further development of their governance innovation that ultimately made their network building effort more effective and inclusive. While initiatives not involved in a research project may not have access to the same kind of conceptual and methodological support, InnoForESt will provide a practitioner-oriented brief manual which details the steps to take when conducting a stakeholder analysis (see Sattler 2019/D4.1, Aukes et al. 2020/D5.5).

The InnoForESt Approach

The InnoForESt approach to bringing stakeholder together is based on close collaboration between all partners in a case-sensitive manner. InnoForESt uses the so-called Ecosystems Service Governance Navigator & Manual for its Use (Aukes et al. 2019/D5.1) developed over the first year of the project in close collaboration with all partners and in close exchange with them about what needs and can be done under each regional circumstance. It entails a compendium of ‘heuristics’, understood as a set of practical tools (yet rooted in theory) integrating the project knowledge generation and communication approach to forest ecosystem services (project glossary, analytical framework, fact sheets, typologies, workshops, etc.). It aims at giving orientation, not setting hard rules.” (Aukes et al. 2019:1). The updated version of this InnoForESt Deliverable (Aukes et al. 2020a/D5.5) will be publicly available from the end of December 2020. This Navigator looks at the approach in retrospect on the completed project and draws numerous examples and references from studies accompanying the innovation efforts that have since been completed.

The approach is based on the assumption that two requirements need to be met in order to have a chance to get innovations off the ground: the basis in thorough research into the current initial situation and past efforts to achieve something similar (comprehension and recognition of the real, existing Forest Ecosystem Services (FES) governance problems) as well as personal, continuous, and trusting cooperation in the IRs with local partners and stakeholders (i.e., real stakeholder inclusion and recognition). We have always been guided by the premise that the innovation work is not an end in itself of an artificially created project from Brussels, but must be based on the real needs and perspectives of the stakeholders themselves. Finally, it is about their real economic and forest-ecological existence, so InnoForEst is not just an abstract exercise.

What is crucial about applying the approach?

The InnoForESt approach has been designed to fulfil an Innovation Action . The aim was, on the one hand, to initiate new governance innovations or to give existing ones a new boost, and, on the other hand, to develop and test prototypes of these innovations. This means that IF did not primarily conduct research for its own purposes, but employed research approaches and methods as a means to conceptually, methodologically, and empirically support actual ongoing innovation work ‘on the ground’. The main tasks in the IF project thus revolved around coordination, assistance, reflection, and training. This deliverable also takes this primary set of tasks into account.

Coordination concerned the cooperation between the various IRs and the overall project as well as that between the work packages and the regions. Project meetings for mutual exchange had to be coordinated as well as the daily work and research with which the innovations were to be initiated and advanced. Assistance was the continuous support of the innovation efforts in the regions by those project members who led the research and the interactions with the stakeholders. Reflection revolved around making content and procedures that had emerged in one place and perhaps even proven to be available as ideas to the other partners. It should also enable a learning curve and contribute to replication and upscaling. In the course of this, it was also clear that a whole range of skills had to be carried into the broader project through training offers. Given the very heterogeneous disciplinary background of project members and the great variety of concepts and methods employed in the project, key training areas had to be reduced to a few common denominators, such as core approaches to preparatory research (on Governance Situation Assessment, Aukes et al. 2019/D5.1; on Stakeholder Analysis, cf. Schleyer et al. 2018/D5.2), carrying out strategic workshops (CINA approach, cf., Aukes et al. 2020a/D5.5), and documentation of the innovation work (cf. Aukes et al. 2020b/D4.2). This was considered crucial for the implementation of a consistent approach to stakeholder participation, prototype creation, and comparability of results.

Contribution based on Aukes et al. 2020/D5.4

Structured, Facilitated Stakeholder Network Building

After the systematic stakeholder identification, the IRs went through a structured stakeholder network building process aimed at collaboratively developing (further) a governance mechanism suitable to spark innovations. The respective regional processes were initiated and accompanied by a team of scientists. They followed a particular method called ‘Constructive Innovation Assessment’ (CINA), which is based on a scenario-based methodology previously developed for assessing newly emerging technologies called Constructive Technology Assessment (CTA). A key element of CINA is developing alternative scenarios for different governance innovations and engaging all relevant actors together at an early stage. It entails a series of workshops, which allows for a continuous innovation development. One or more workshops focus on innovation analysis and visioning, prototype development, and road-mapping (see also Aukes et al. 2020/D4.2, Aukes et al. 2019/D5.1).

Certain key elements of this process were deemed particularly important by practitioners and were considered recommendable to other initiatives pursuing their own governance innovation:

- Taking time; an effective stakeholder engagement process requires substantial amounts of time to accommodate identification of relevant stakeholders (see also paragraph above), as well as preparing, implementing, and following up on actual workshops and other meetings. If a series of meetings is implemented, leaving enough time to reflect on each event’s developments and results is crucial.

- Meeting in person and meeting regularly; in-person meetings with and among stakeholders are described as a valuable opportunity to get to know stakeholders, their perspectives, challenges and needs, and for exchanging ideas. Organising multiple workshops and other meetings enables a comprehensive collaborative process of developing a common vision for the initiative, but also offers valuable time spans for the IR practitioners and scientists to reflect on the workshop outcomes. A series of meetings also allows for the necessary flexibility in terms of accounting for – or even integrating – newly emerging issues, or including additional stakeholders into the process.

- Engaging external actors; several IRs invited external speakers, or hired external moderators for one or more of the workshops. Their involvement was reported to have been beneficial to the innovation process and for stakeholder engagement. Having an external speaker present on a topic local stakeholders are interested in has served as a ‘pull factor’, and is thought to have attracted more participants to the workshops. Further, they often presented ‘fresh’ ideas, best practices, but also insights on challenges and failures, which informed the (further) development of the governance innovation under scrutiny. External moderation of discussions is reported to have benefited the workshop’s quality and discussion results, too. Professional moderators have capacity, knowledge, and experience to plan and implement an effective workshop, or support non-professionals in their efforts. This includes providing practical guidance on tools, methods, and moderation techniques available to use in the workshop, for example, for structuring plenary discussions and group work, but also for documenting discussions and workshop outcomes in a non-academic, everyday language, as well as providing easy-to-follow guidance on workshop management to practitioners, including scheduling, timing, and reflecting on workshop outcomes.

- Context knowledge and trust: having continuity with regards to individuals involved in the network building processes and scenario development (see below) is essential. Those who have carried out preparatory research (e.g. stakeholder analysis etc.) and have built a level of trust through numerous discussions and meetings with stakeholders, play a key role in (CINA) workshops. They can contribute the familiarity with stakeholders and issues necessary for successful collaboration and mobilisation of workshop participants.

The InnoForESt multi-actor-approach

Had foreseen and proved stakeholders’ engagement as key for exploring innovation potentials for governing FES sustainably and for putting them into use. The identification of practice-relevant problems and the perception of these problems, interests and demands, as well as the collaborative development of innovative and practice-relevant governance solutions are therefore highly dependent on the successful and comprehensive identification of and engagement with stakeholders in the IRs. To ensure a certain standard of stakeholder characterisation and governance context description and to allow for some comparability of results across IRs, the implementation of training approaches for preparing and conducting the Stakeholder Analysis and, later, the Governance Situation Assessment in the IRs was crucial. This enabled IR teams to gain implicit knowledge as well as identify knowledge gaps about stakeholders, institutional arrangements, and policies, and to help them gather new information that may support ‘their’ innovation processes.

Contribution based on Aukes et al. 2020/D5.4

Facilitated Innovation Development

Innovation is a social process within given cultural, scientific, technological, political and continuously changing context. It is not a straight-forward, linear process that can be programmed or would lead to precisely defined results, but is often experienced or observed as open-ended. In order to achieve anything, managers and policy-makers “are to go with the flow – although we can learn to maneuver the innovation journey, we cannot control it” (van de Ven et al. 1999: 213).

Based on this insight, CINA orchestrated a set of workshops with a range of stakeholders for (1) Innovation analysis and visioning; (2) Prototype development, and (3) Roadmapping (Loft et al. 2020/D4.3, Schleyer et al. 2020/D5.4). One major element of the CINA workshops is the development of scenarios with stakeholders. Both the process of working together to develop them as well as their actual content – the scenarios themselves – were identified by practitioners as key elements of the overall innovation [development] process; scenarios enabled a strong identification of stakeholders with the IR’s goals, but also provided clear focal points for discussion and a goal for stakeholders to work towards during the workshops and other events and meetings. At the same time, developing scenarios – but also selecting and discarding them – enables finding stakeholders’ “sore spots”, as one IR practitioners put it, and thus helped to understand better what issues stakeholder are willing to negotiate, and which issues not.

Innovation Journeys

Building on corporate innovations research (Van de Ven et al. 1999, Kuhlmann, 2012) we adapted the concept of an ‘innovation journey’ to describe and analyse innovations as processes (see Loft et al. 2020/D4.3). Along a set of process event categories the innovation development was reconstructed. This encompasses the socially enacted interactions between our IRs as “niches”, the established regimes as well as other socio-cultural, economic and political landscape developments and trends, against the background of which the more specific dynamics of particular regimes and niches evolve (Geels 2002; Geels and Schot 2007; Rip 2012).

With this co-evolutionary perspective on the innovation process and its context, we imagine innovation as a journey into uncharted waters and although we can learn to maneuver the innovation journey, it is important to realise that it cannot be controlled (van de Ven et al. 1999). In other words, innovation processes are not a matter of control, steering and management.

Our empirically grounded and theoretically informed conception of the innovation journey (Loft et al. 2020/D4.3) allowed us to capture the uncertain open-ended process by reconstructing precisely the open ends and uncertainties as well as the more or less organised social actions and negotiations, and to identify patterns and typical key components.

We found that innovation development does not take place in isolated space. It is influenced and influencing essential context conditions. For innovation development the strategic orientation, i.e, the overarching aims and objectives are essential. Real world innovation development does not take place under ideal “laboratory” conditions. Rather it is shaped by problems, crises, stagnation and setbacks. A closer look at the Innovation Journeys has revealed that (1) innovation processes have a rhythm, (2) which is very different depending on the local and historical situation in which it is embedded, (3) which is not simply going into the direction of the new, towards progress and (4) that stakeholder networks develop along with the rhythm of the innovation process. In addition, the role of the Constructive Innovation Assessment with its multi-phase approach became clearer.

Contribution based on Loft et al. 2020/D4.3

Payment Mechanisms for FES Provision

The IRs involved in InnoForESt showcase a number of different approaches to funding FES provision: all actively address private economy mechanisms that contribute to securing the provision and financing of regulating and cultural FES. They range from crowdfunding (CZ: biodiversity), and sponsoring (SE), to communal forests and private enterprises involved in regional forest-wood value chains (SK, AT) and compensation (FI: biodiversity, DE: carbon emissions), and again others work with combinations thereof (IT).

The FES-related payment mechanisms and business models detected can be grouped into main three categories:

- Compensation payment mechanisms for forest management offsetting negative ES footprints: Primarily direct payments for biodiversity conservation or carbon sequestration. Thus, forests no longer provide income (solely) based on their (timber) productivity, but rather through their ability to compensate for negative ecological and climate effects of other production processes elsewhere.

- Value added in regional forest-wood-value chains from multi-FES oriented forest management: Timber production and processing of innovative wood-based products contributes to refinancing forest management decisions beyond provisioning FES.

- Business models of other sectors dependent on forests and their FES as a backdrop.

So far, none of the IRs was yet able to establish a self-sufficient economically sustainable private market financing mechanism or business model for the provision of regulating and cultural FES. All developments are still ongoing and largely shaped by dynamic changes in context conditions, often being subject to policy changes. Most of the innovative payment mechanisms and business models currently implemented were found to be dependent – at least to some extent – on some form of public involvement, and are perceived to continue to do so in the future as well.

This public involvement can take different forms: for the documented compensation payment mechanisms, public entities are found to be intermediaries managing transactions between forest owners and customers willing to purchase offsets (FI); municipalities are one potential buyer of these forest ecosystem services, alongside companies. (FI); Municipalities also have the option to carry out the offset on their own public lands (FI) or the state forest administration provides public land for planting ‘climate forests’ by others and later maintains these reforestation sites (DE). Practitioners in CZ, FI conclude from their project experience that a government decision for obligatory compensation measures is needed to get compensation payment schemes well-functioning. Value-adding innovations in regional and diversified forest-wood-value chains are often supported by local public procurement (AT). Intersectoral innovative business models relying on forests and FES as a backdrop are currently designed and supported by non-profit organisations such as the tourism association (AT), educational organisations (SE), and non-profit NGOs, which again receive public funds. The objective to maintain forest–pastures with high levels of regulating and cultural FES plus related private business incentives in a mosaic of public-private land ownership (IT) hinges, among others, on the administrative capacity supporting stakeholder network building and on public funding being granted. All IRs and FES related innovation processes have reportedly benefited from public financial grants to non-profit NGOs and scientists providing goal-oriented systematic networking and methodological support within and beyond their local realm.

Cross case analyses on key factors influencing governance innovations

The process of factors identification and analyses has been defined for the identification and reconfiguration of key factors for innovative activities towards sustainable forest ecosystem service provisioning and financing developed in co-production of theoretical, expert and empirical knowledge. When the historical and current setting of governance innovations is known, strategies and policy recommendations can be developed to transform the innovation into the next desired future step, namely the next innovation stage or the next level application scope.

Theoretical knowledge on influencing factors is derived from the SETFIS analysis framework as described in detail in Sorge and Mann, 2019/D3.1. Initially, we identified 75 factors in 6 dimensions: the Governance System, including Actors and Institutions; the Biophysical Ecosystem; the Forest Management System; the Innovation System; the External Factors and the Governance Innovation Process. Those dimensions and their factors have been translated into questions for in depth interviews in all Innovation Regions. The results provided a detailed insight on the development of governance innovations, reduced the set of most influencing factors and exemplified dynamics between the factors. This helped us to better understand the innovation due to making certain processes and patterns of actors within the innovation process visible. This experience is shared and translated into recommendations to possibly not only improve (upgrade) and increase the level of applicability (upscale), but also to possibly reproduce such governance innovations into other regions with related contexts.

Following consultations with the representatives of IRs as part of CINA process and the InnoForESt consortium, 40 most relevant factors were selected and finally validated in an online survey answered by 17 representatives of IRs.

In a final step of the analysis we linked the identified influencing factors with potential innovation trajectories to identify smart innovation patterns and road mapping strategies, and for the derivation of policy and business and management recommendations.

Table 2 demonstrates the 17 most important factors for sustainable ecosystem services governance innovations. The level of importance of each factor was assessed on the scale from 1 to 5 (Most important = 5, Least important = 1), finding an average score of 4 or higher).

The results of factors analyses (Table 2) indicate a possible grouping of factors into three clusters referring to i) institutional robustness of forest communities ii) local biophysical conditions and policy support (such as FES as economic model) and iii) innovation friendly behaviour (proactive payments for ecosystem services, social economy). These can create a basis for smart innovation patterns that are now being developed.

Moreover, further results from the factors analyses indicated impact of relevant policies at different governance levels on innovative activities. A majority of respondents from IRs identified local and EU policies as the most enabling or fostering policies for their innovations for sustainable FES provision. On the other hand, national policies are seen as the most hindering for IRs activities and a majority of respondents demand their change/redesign (similarly for regional policies which, however, were perceived much more positively).

Contribution based on Kluvankova et al. 2020/D3.2

| Factor | Factor validation (average) |

Factor assessment (prevailing) |

|---|---|---|

| Strong leadership/leading group/intermediary | 4,65 | Fostering |

| Network collaboration | 4,41 | Fostering |

| External social/political influence | 4,35 | Fostering |

| Sharing information | 4,29 | Fostering |

| Communication on forest ecosystem services and their contribution to human wellbeing | 4,29 | Fostering |

| Innovation-friendly environment | 4,24 | Fostering |

| Impact of the innovation on forest ecosystem services provision | 4,24 | Fostering |

| FES Demand | 4,24 | Fostering |

| Flexibility of application scope | 4,24 | Fostering |

| Sharing knowledge & training | 4,24 | Fostering |

| Flexibility and openness to include new actors | 4,18 | Fostering |

| Policy Support | 4,18 | Fostering |

| External economic influence | 4,18 | Hindering |

| External support | 4,12 | Fostering |

| External biophysical influence | 4,12 | Fostering |

| Related innovations | 4,06 | Fostering |

| Influence of local orientation | 4,00 | Fostering |

Legend: Assessment of relative importance of influencing factors: 1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neither disagree nor agree; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly agree.

Source: InnoForESt Factor Assessment Survey in Kluvankova et al. 2020/D3.2

The following recommendations and options for action to develop functioning private, market oriented payment mechanisms for the provision of FES reflect one or more of the above described overarching themes; the role of each of the six targeted actor (groups) – forest owners and managers, NGOs, entrepreneurs, local policy-makers, national and EU policy-makers, scientists and entities funding future research – can play regarding any one of these themes depends on the actor group’s particular position, resources, and expertise (see also Table 2). They were written with the aim of concise recommendations that provide readers with all necessary information and hints to further information, independently of reading the entire report. A certain level of redundancy across the individual recommendations is a necessary trade-off to this “stand-alone approach”.| Actor groups addressed → —————– Overarching themes |

Forest owners/ managers/ administrations | NGOs & Associations | Entrepreneurs | Local policy-makers | National and EU policy-makers | Scientists |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maintaining direct link to FES provision | Pro-active | Pro-active | Pro-active | Pro-active | Pro-active | Pro-active (methods) |

| Bringing diverse stakeholders together | Pro-active | Pro-active | Pro-active | Creating supportive conditions | Creating supportive conditions | Creating supportive conditions (methods) |

| Structured, facilitated network building | Participating | Pro-active | Participating | Creating supportive conditions | Creating supportive conditions | Creating supportive conditions (methods) |

| Facilitating Innovation development process | Participating | Pro-active | Pro-active | Creating supportive conditions | Creating supportive conditions | Creating supportive conditions (methods) |

| Payment mechanisms for FES provision | ||||||

|

X | X | (X) | X (public support) |

(X) (regulations, public support) |

X (evaluation, monitoring) |

|

X | – | X | X (public support) |

(X) (regulatory conditions, public support) |

X (product & chain dvlp.) |

|

(X) | X | X | X | (X) | X |

Legend:

X = InnoForESt has identified a potential role for this actor in the context of the respective overarching theme

(X) = perceived potential role without examples within InnoForESt

– = InnoForESt has not identified a role for this actor in the context of the respective overarching theme

2.1 Forest owners and managers

Forests across Europe are owned and managed by various types of forest owners, primarily public forest owners on national, state, communal, and local levels, as well as private forest owners, typically differentiated into large- and small-scale owners. Management activities are carried out either by the private owners themselves, co-operatives, contracted entrepreneurs, or – mainly on public land – the forest administration. The proportion of public vs. private, large vs. small forest ownership varies across Europe, as do forest types and management objectives. Nevertheless, forest owners do share similar challenges when it comes to financing the provision of FES. In brief, it is becoming increasingly difficult to generate profit based on the production and sale of timber due to unsustainable global markets for forest products, climate change, etc. At the same time, societal demands towards forests are growing and becoming more diverse, including for biodiversity conservation, recreational opportunities, and using forests as carbon sinks. Forests provide a range of FES and can be managed to provide a particular (set of) FES in greater quality and or quantity. Yet forest owners typically do not receive (sufficient) reimbursement or financial support especially for the regulating and cultural ecosystem services their forests provide, to incentivise management activities that would maintain or increase their supply (see Figure 1). As a result, despite high societal demand, many non-provisioning FES tend to be underprovided or even decrease because those able to provide them – forest owners and managers – thus far do not receive sufficient compensation.

Maintaining direct link to FES provision and financing

When collaborating with other stakeholders, forest owners and managers play a key role in making sure the link to forest management and FES provision and financing as well as other FES-related objectives are considered throughout the innovation development process. Recommendations include to:

- contribute your forest-related knowledge to discussions about FES provision and financing or their role as backdrop for other economic initiatives.

- collaborate with suitable organisations to assess the current supply and demand of FES in your region, and evaluate the quality and quantity of FES currently provided as well as the potential for improvements including necessary measures to take.

- request an assessment of any innovation process concerning the potential for improvements or potential negative impacts in quality and quantity including necessary monitoring measures to be taken.